Zadie Smith’s White Teeth is a family saga that addresses issues of imperialism, the impact of culture and religion on the individual and the fate of liberal democracy. It’s an ambitious novel and it may sound intimidating, but it’s one of the best books I’ve read for a while. It is also tightly plotted, highly readable, extremely funny and very intelligent. There are stark social and moral dichotomies at play in this book. On one side there are characters guided by their connections to history, to family and religion, like Samad, a Bangladeshi immigrant to England. On the other, characters like Marcus Chalfen and or Samad’s son, Magid, who becomes Chalfen’s confidante and help, are driven purely by rational considerations which blind them to the moral implications of their work.

Smith’s novel seems consciously written in response to Francis Fukuyama’s political work, The End of History and the Last Man. In fact, Smith gives Fukuyama’s title to a chapter late in her book. Fukuyama’s idea that history might end was not suggesting that things would cease to happen. Rather, it was a belief that Western liberal democracy was the inevitable end result of the historical process, in contradistinction, say, to Marx and Engel, who posited that history was moving towards a worker state. Fukuyama wrote his book after the fall of the Berlin Wall, an event that appears in Smith’s narrative, and what seemed the final ascendency of America as the world’s only superpower. I remember reading a TIME article near the end of the nineties that also reflected Fukuyama’s assessment. Marking the handover of the Panama Canal to Panama at the end of 1999, Charles Krauthammer wrote:

Last week's handover of the Panama Canal neatly brackets the American Century. It begins with Theodore Roosevelt conceiving the canal and, with it, America ascending to the rank of Great Power. It ends with America so great a power, so serenely dominant in the world, that it can give away T.R.'s strategic jewel with hardly a notice.

But if the 20th century was the American century, the 1990s – bracketed by demonstrations of overwhelming American power in Kuwait and Kosovo – were the supreme American decade. How supreme? No other nation has exercised such military, economic, diplomatic and cultural reach since Rome.

And while Zadie’s Smith’s White Teeth is set in England, not America, the issue is the same. The history of Western and Eastern culture is one of exploitation and paternalism. The history of Britain in India, for instance, is one of exploitation – the East India Company which gave Britain a de facto colony – and cultural imperialism. As such, White Teeth has elements of a Post-Colonial narrative, but at the same time is a critical response to Western triumphalism and monolithic ideologies.

Despite its broad themes, the book is a domestic drama of three families. Archie, a white Englishman and Samad, a Bengali, meet near the end of World War II. They are a part of a tank crew for whom the war ends without their knowledge. With their tank broken down they are forced to survive in a small village as they attempt to make repairs and avoid the same fate as their crewmembers, murdered during their absence. Their friendship survives the war and their families are intimately connected for the next forty years. Archie and his wife Clara, a dark-skinned woman with missing front teeth whose family is from Jamaica, produce a daughter, Irie. Samad and his wife Alsana have twin boys, Magid and Millat. The third family, the Chalfens, are a white middle-class English family. Irie and Millat become involved in their lives after their school principal directs them to have study sessions at the Chalfen house, along with the Chalfen son, Joshua, with whom they have been caught with at school in possession of marijuana. Marcus Chalfen is a genetic scientist whose experiment on a mouse, the FutureMouse, promises to push forward medical knowledge and is destined to make him a celebrity. His wife, Joyce Chalfen, is a horticulturalist with a radio program.

It is significant that the Irie and Millat are sent to study at the Chalfens. Education is a point of conflict in the novel. For Hortense, Clara’s mother, education represents the power to repress, be it through sex or race. As a devoted Seventh Day Adventist she is rankled that scripture might only be interpreted by men. As a Jamaican labourer, her mother, Ambrosia, had Western education imposed upon her as part of a process of indoctrination and sexual exploitation. During the Jamaican earthquake in 1907, Ambrosia’s response to a summons to escape with her employer derives from Job: I will fetch my knowledge from afar

.

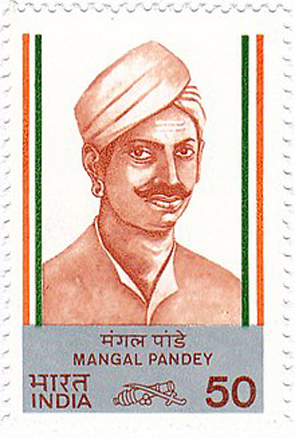

Samad’s identity is consumed by his famous great-grandfather, Mangal Pande, an Indian soldier credited with sparking the Indian Mutiny of 1857 when he attacked British soldiers. Pande is an important symbol of Samad’s family pride, especially as he feels emasculated by his poor-paying job as a waiter and a wife who can beat him physically in a fight. Angered that his great-grandfather’s memory has been sullied by British history – portrayed as a drunk, irrational failure – Samad seeks to redeem his memory and take pride in the legacy of self-determination and independence Pande represents for him. And in an attempt to raise at least one son as a good Muslim boy free of Western influence, he sends his eldest twin, Samid, back to Bangladesh.

This is the difference between Western and Eastern characters in this novel. From a Westerners point of view,

we often imagine that immigrants are constantly on the move, footloose, able to change course at any moment … [to] step into their foreign lands as blank people, free of any kind of baggage, happy and willing to leave their difference at the docks and take their chances in this new place, merging with oneness of this greenandpleasantlibertarianlandofthefree.

This assumption is based upon a Western understanding of historical imperative. For the immigrant, history is alive, forms a part of their consciousness and understanding of the world; their culture and religion. This is a progressive view of the world, in which the individual is improvable. But the Western view – the world in which liberal democracy has won (the Berlin Wall is gone; the Soviet Union has fallen apart and the West is ascendant), we exist in a temporal instant in which liberal democratic values are naturalised by eliding their historicity. Western identity is predicated upon having attained political and cultural perfection in nowness. This is a static view of the world in which the individual is perfectible, not through spiritual or individual growth, since those are presumably attained by embracing Western education and its beliefs, but through the physical self and consumption. The sexualisation of women in Western culture is antithetical to Muslims like Samad. The presumption that humans might be perfected beyond God’s creation through genetic modification, therefore, is not to be borne.

Marcus’s experiment, the FutureMouse, that has had its genome altered so that it might live for a predetermined time and develop sicknesses predictably, is a demonstration of the power of science to control Fate (Interestingly, a group who protest the experiment have the acronym ‘FATE’). Marcus’s experiment is driven by idealistic desires to cure disease, but its unintended result is that it challenges the human notions of what is natural, authentic and ordained, as expressed through morality and religious belief.

And this raises an interesting aspect of the novel for those who see it as a Post-Colonial dissection of Western Colonialism, only. Smith sets up the West as a monolith represented by educational, scientific and political paradigms. But as much as Western versus immigrant experience might be expressed by the dichotomy of present and past, of moral and immoral, as lives lived conditionally and chaotically against lives lived safe and assured; as much as this is about science and religion or God against self-pride, the novel is also concerned with closed systems that deny the reality of the Other. Said’s concept, now, is not turned purely upon the exotic, but the Othering of science as much as it is about the Othering of culture or religion. Marcus, a genius by anyone’s standards, naively believes his work in genetics is apolitical and fails to understand the resistance it meets in the community. At the same time, his work is opposed by older monolithic ideologies. Samad believes the word of Allah can be rationally proved to anyone just as a scientific principal might be, and Ryan Topps, a Seventh Day Adventist, believes faith alone is unshakable: faith is the biggest fuck-off light sabre in the universe

. What any ideological positions avoids is the reality that Samad’s wife expresses: that human endeavour, human living, is a process of involvement. That each person is connected to each other, and is complicit in their history. Our children will be born of our actions. Our accidents will become their destinies.

Samad tells Archie at the beginning of the novel. And so, it seems, there is an endless cycle of histories that seem to repeat from one generation to the next, and good intentions that result in unexpected consequences.

The individual, it seems, is like a tooth without a root: unstable. For an individual to be stable, they must have roots – a past – so it is not surprising that root causes

are the subject of much of the narrative.

Of course, this is conditional. Smith is an artist not a proselytiser, and her book is an exploration rather than a flag stamped into any one territory. Irie decides she want to be a dentist, but she rails against the obsessions with the past that are tearing her family apart:

Irie has seen a time, a time not far from now, when roots won’t matter any more because they can’t because they mustn’t because they’re too long and their too tortuous and they’re just buried too damn deep.

It is these seeming contradictions that make the book rich in thought, tightly twined around key ideas that begin with the fate of individuals but unravel into a world where culture is still dynamic and history is yet to be written.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed Facebook

Facebook Instagram

Instagram YouTube

YouTube Subscribe to our Newsletter

Subscribe to our Newsletter

No one has commented yet. Be the first!