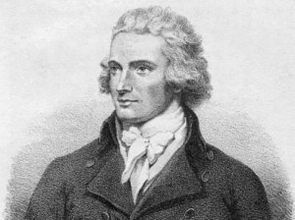

Water Music is a rollicking adventure. It’s an entertainment: a story of doomed love, of betrayal, of graverobbing, of exploration into the deepest heart of the African continent, and it even has a sex scene involving the Loch Ness Monster. What more can you ask from a book? T.C. Boyle’s first novel is an accomplished piece of storytelling, combining the real history of Mungo Park’s two expeditions to chart the course of the Niger river in Africa during the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries, along with the fictional story of Ned Rise, a man from the poorer part of London, hoping to rise in the world. In his attempts to make something of himself, Ned will host pornographic theatre, sell ‘Russian’ caviar to the wealthy (sourced from the Thames) and will find himself at the mercy of an unscrupulous physician competing for cadavers on the open market.

All this, in Boyle’s assured hands, adds up to a gripping episodic story, picaresque in style, while also being an appealing postmodern take on history. There is an open playfulness to this novel which the author signals in his ‘Apologia’ before the whole thing begins: I have been deliberately anachronistic, I have invented language and terminology […] Where historical fact proved a barrier to the exigencies of invention, I have, with full knowledge and clear conscience, reshaped it to fit my purpose.

Boyle gives himself permission to flout the rules and dares the reader to play along. I found myself looking for his anachronisms. A short list: there is a reference to corrective eye surgery in a chapter heading just after Mungo almost loses his eyes to a torture device consisting of screws - something like an inverted chastity belt

; there are references to Tennyson’s ‘The Charge of the Light Brigade’ and ‘The Lotus-Eaters’, written half a century after this story; Mungo worries that his chest might be branded with an ‘A’ if he is caught with the Emir’s wife, a clear reference to Hawthorne’s The Scarlet Letter; Mungo recites a version of Edward Lear’s ‘The Owl and the Pussycat’; and there was a minor character – Squire Trelawney – whose brief presence reminded me of Stevenson’s Treasure Island, another novel of adventure (and dare I say piracy?)

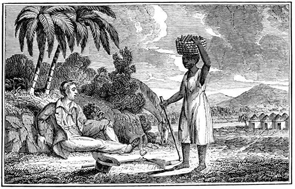

The question, while somewhat coy, is also pertinent. History must remain relevant to modern readers. History that fails to be relevant is merely a set of facts and circumstances, perhaps interesting to a specialist or enthusiast. Living history, however, speaks to us and our condition; its territory is negotiated, its meaning debated, its interpretation moving with the tide of modern opinion. So, Boyle presents us with a boys-own-adventure – delving into the heart of Africa, outwitting and outrunning the natives, pushing the boundaries of knowledge and receiving accolades – but he tempers this traditional tale with modern perspectives. Mungo Park, while not an evil man, per se, is somewhat oblivious to the implications of his explorations. Mungo is focussed upon his reputation. What he really wants is fame, not travails and danger, not the tedium of recording his knowledge for posterity. In his second expedition, when he encounters resistance from tribes along the Niger, he is frustrated that they cannot see the benefits that trade will bring them with England. Yet Mungo’s own experience shows us that colonialist powers exploit Africa rather than deal fairly with its nations. In his attempts to return to England after his first expedition he joins a slave ship bound for South Carolina, and acts as ship’s surgeon. He sees the misery of the slaves and the loss of life the trade brings, and is moved to speak for the humanity of the blacks on board. But frustrated ambition and personal danger change Mungo. In attempting to secure finance for his second expedition he emphasises the commercial possibilities in exploiting Africa. He is later willing to sell a rival to cannibals. As his second expedition meets resistance from African villages, he is willing to use his superior fire power to slaughter blacks and sink their canoes. His growing cynicism is predictably met with an overwhelming violent response. Mungo Park’s actions raise the question, at what point does exploration and trade become exploitation and piracy?

It is precisely this kind of revaluation that Boyle’s postmodern approach allows. Another minor character, the charmingly-named Lord Twit, argues, And what is history, pray tell, if not a fiction.

Despite his unfortunate appellation, Twit is insightful enough to understand history’s contingency, upon hearsay, thirdhand reports, purposeful distortions and outright fictions invented by the self-aggrandizing participants and their sympathisers.

Twit questions the knowledge of the ancients, the set-in-cement received wisdom that ossifies attitudes and supports the contempt and assurance of white attitudes towards Africa.

Boyle’s novel, therefore, becomes less a story of exploration, than a tale of attempted conquest. Park’s violent treatment of the African tribes in his trip down the river of his second expedition makes this obvious, but the signals are there from the beginning. When Park sleeps with the Emir’s wife during his first expedition – a woman of corpulent proportions, revered for the status of wealth her girth endows upon her husband – it is an act of conquest rather than lust: He scrambles atop her, feeling for toeholds – so much terrain to explore – mountains, valleys and rifts, new continents, ancient rivers.

Later, his future wife, Ailie, will languish at home, waiting for Mungo to return. Life in England – the prospect of a large family and a medical position – is quotidian and has little attraction for Park.

In reshaping our perceptions Boyle turns to the motif of his title. ‘Water Music’ was a series of movements written by Handel for George I and was originally played on the River Thames to reassure the public (and no doubt the King) of his culture and importance. ‘Water Music’ was played at other times after that, but in Boyle’s novel it is Handel’s ‘Requiem’ that is played during the Christmas of 1797. It reminds Park that he was Back in society where the forms are observed and the love of culture is a way of life.

Superficially, it would seem, music is meant to create a false dichotomy between the civilised and the uncivilised; between England and Africa. But Boyle is too subtle an author for that. Later, it is the desire for adventure again that draws Mungo Park back to Africa, felt by Park as a song in his dreams, the music of the Niger, drawing him back. Far from allowing such a dichotomy to degrade African civilisation, it suggests the opposite. While London suffers under the fetid conditions associated with a painting by Hogarth (A carriage rattles up the street and splashes the side of the compartment with dung. Two blocks up a baby falls from a window

), Segu, the capital of Bambarra, is portrayed as an exciting cosmopolitan city of plenty (They pave their streets with marble, tradesmen eat from gilded plates, food is for the asking: fowls and poached fish, eggs, mutton, rice.

). Africa may be a hard place to live, but its civilisation is marked by cooperation. In the village of Song, Mungo observes the villagers working, their actions harmonised through music: each was attuned to the other through the rhythmic insistency of the song. Order and harmony, sang the voices, cooperation and prosperity, heave and ho.

Twit’s point, however – that history is a fiction

– does not entirely capture the truth of it. I read this novel over a two-week period in which protests broke out across America and the world in support of ‘Black Lives Matter’ after George Floyd was killed by a police officer who knelt on his neck. This formed the context of my reading which cannot help but inform my reading of Boyle’s novel. The idea that history is fiction is not a nod to Trump’s ‘fake-news’; rather, it acknowledges that historical discourse is shaped by perspective and power. Mungo Park’s story is traditionally empowered by white colonial perspectives. But Floyd’s death is the latest black death that demonstrates it is possible to question dominant discourses and demand that history reflect other realities. That history is not neutrally received but negotiated according to a set of values. That has been the impetus behind many statues deemed to glorify the memory of racist and exploitative white men either being defaced or removed this week. So far as I know, Mungo Park’s statue in Selkirk, Scotland, has not been touched this week. Park generally seems to be revered for his adventurous life and his achievements: he was the first Westerner to travel the Niger River and determine its course. But Boyle’s novel reminds us that those achievements are not neutral either: they come at the personal expense of family and are part of a wider historical context of exploitation.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed Facebook

Facebook Instagram

Instagram YouTube

YouTube Subscribe to our Newsletter

Subscribe to our Newsletter

No one has commented yet. Be the first!