In May 1845 Sir John Franklin set sail from England with two ships to chart the Northwest Passage. The expedition was lost and never heard from again. Many expeditions were sent to look for the lost ships, and some of those also met with disaster. Later evidence suggests that Franklin’s ships had become icebound and his men mostly died of hunger or disease. Circumstances became so grim that, according to a report by Dr John Rae who had spoken to Inuit tribes in the area, some of the expedition members had resorted to cannibalism. Lady Jane Franklin, Sir John’s wife, refused to believe these reports and would regularly press for the search to continue. Many rescue expeditions were mounted, so that the charting of the Northwest Passage was completed, despite Franklin’s disaster.

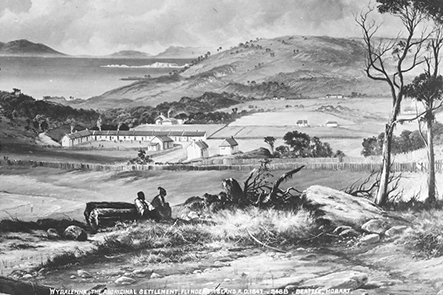

On the other side of the world in Van Diemen’s Land, now known as the southern state of Tasmania, Australia, the problem of what to do with the Aborigines weighed upon the government and other humanitarian organisations. A bitter war had been fought against the Van Diemen Aborigines. That, and introduced European diseases, had decimated the Aboriginal population. In 1833 George Augustus Robinson, a representative of Lieutenant-Governor George Arthur, persuaded many of the remaining Aborigines to surrender. They were taken to a settlement at Wybalenna on Flinders Island. Disease continued to kill Aborigines in this new settlement at an unnatural rate. Eventually, the last full-blood Tasmanian Aborigine, Truganina, would die in 1876. The belief that the Tasmanian Aborigines were therefore extinct was long assumed, although many people in Tasmania still claim Aboriginal descent, including the author of Wanting, Richard Flanagan.

Flanagan’s novel takes as its subject these seemingly disparate 19th Century stories. The link between them is the leader of the Northwest Passage expedition, Sir John Franklin. By 1837 when Franklin was appointed Governor of Van Diemen’s Land he had already completed three Arctic expeditions. His fourth, fateful voyage of 1845 was undertaken after his commission in Van Diemen’s Land was terminated in 1843. As Governor, Franklin had officially overseen the measures taken to deal with the treatment of Aborigines under his care.

Chapter by chapter, Flanagan’s novel quite brilliantly moves between these two worlds. It is a novel necessarily based on facts, with reference to documents, books, plays, paintings and real people, but there was a sense while reading it that it is too perfectly wrought for reality; that Flanagan has taken the raw materials of history and fashioned them into an idea so singular and so expertly drawn, that his writing achieves a dual focus: in close focus it is the story of the history I have outlined; but by refocussing – not your eyes, of course, but the way the story invites itself to be read – it is a symbolic representation of human nature and culture, seen through the dichotomy of civilisation and savagery.

So the novel balances both old and contemporary social discourses. On the one hand, ideas are expressed by its characters about various attitudes to savagery and indigenous peoples in the middle of the 19th Century, informed by Rousseau’s ‘Noble Savage’, and later by Darwin’s Origin of Species. On the other hand is the contemporary context of the reader who is able to understand the history of this period and its outcomes, as well as the changed attitudes towards race and colonialism that now inform our own century.

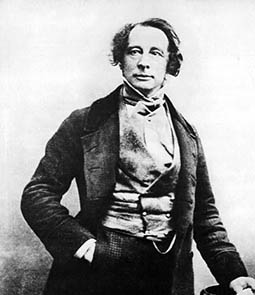

Charles Dickens, the most famous author of the 19th Century, had much to say in response to the idealisation of indigenous peoples as ‘Noble’. In his essay ‘The Noble Savage’, Dickens refers to Native Americans and Zulus as “mere animals” and “extremely ugly”. Dickens’ position isn’t just racist; it is worse. A more accurate representation of this article is that he is reacting against Rousseau’s concept and the fashionable belief in a ‘Noble Savage’. Dickens is also reacting to the power that this idea had in English society at the time, but also against the culture and ways of indigenous people. He represents their speech and behaviour as “howling, whistling, clucking, stamping, jumping [and] tearing.” And he focusses on the exotic appearances of different indigenous people as well as their practices; practices like the blackening of teeth, knocking teeth out, oiling their bodies and tattooing themselves. Dickens wrote,

Yielding to whichsoever of these agreeable eccentricities, he is a savage – cruel, false, thievish, murderous; addicted more or less to grease, entrails, and beastly customs; a wild animal with the questionable gift of boasting; a conceited, tiresome, bloodthirsty, monotonous humbug.

Dickens concludes, “His virtues are a fable, his happiness is a delusion; his nobility, nonsense.”

It may seem a little too much to quote Dickens so extensively to make a point about attitudes in the middle of the 19th Century, except that Flanagan has made Dickens a major character in his novel. Again, there is a connection, and Flanagan uses it to great symbolic effect. In the novel Lady Jane asks Dickens to respond publicly to the suggestions made by Dr John Rae that men on her husband's expedition – possibly even Sir John himself – had resorted to cannibalism to survive. It is not merely a personal slur, but it challenges the very notion of what it means to be English and civilised: “the English public was certain that there was no reason at all to suggest that Sir John – a great Englishman in the stoutest English company ever assembled for such a venture – would not endure where even savages could survive.”

Dickens’ attitudes pervade the text. He writes the response to Dr Rae as requested by Lady Jane. His fame and superior argument are such – Dr Rae is not credited as a wordsmith - that the British public are swayed. Instead of dying by starvation or resorting to cannibalism, Dickens argues, Franklin and his men are more likely to have been killed by the Inuit people who reported his plight to Rae: meaning, that they are not trustworthy. This following is an extract from the response Dickens published in his magazine, Household Words, December 1854:

Lastly, no man can, with any show of reason, undertake take to affirm that this sad remnant of Franklin's gallant band were not set upon and slain by the Esquimaux themselves. It is impossible to form an estimate of the character of any race of savages, from the deferential behaviour to the white man when he is strong. The mistake has been made again and again; and the moment the white man has appeared in the new aspect of being weaker than the savage, the savage has changed and sprung upon him.

It is a sentiment Flanagan paraphrases into the words of Lady Jane as she asks Dickens to undertake the task of rescuing her husband’s reputation: “It is impossible to form an estimate of the character of any race of savages from the way they defer to the white man when he is strong.” In short, native people are not to be trusted. Deference to civilisation is merely pragmatic and there is a gulf between the culture of an Englishman and the people of the wider world.

This is a sentiment which forms a thesis within the novel. A series of extracts makes the point clear:

‘. . . You see Mr Dickens, the distance between savagery and civilisation is – ’

[. . .]

‘The distance Ma’am, is the extent we advance from desire to reason.” He would not tell her his whole life was an object lesson in control of one’s passions . . . ’

[page 29]

* * * * * *

. . . the mark of wisdom and civilisation was the capacity to conquer desire, to deny and crush it.

[page 47]

* * * * * *

‘We all have appetites and desires. But only the savage agrees to sate them.’

[page 79]

* * * * * *

‘A savage, my dear Wilkie [Collins], be he Esquimau or an Otaheitian, is someone who succumbs to his passions. An Englishman understands his passions in order to master them and turn them to powerful effect.’

[page 83]

* * * * * *

. . . the child was about to embark on a rigid programme of improvement. No moment was to be wasted, and all reckless passions were to be subjugated to the discipline of industry.

[page 115]

* * * * * *

‘The distance between savagery and civilisation is measured by our control of our basest instincts.’

[page 126]

This is just a sample of this litany. That the author repeats this idea so often might be reason to question his technique: perhaps that it is too unsubtle, or that it represents poor editing, or that the thematic scope of his writing is too narrow. But this is not a representation of Flanagan’s position, we have to remember. This represents the certainties of Dickens’ world and the attitudes of Flanagan’s protagonists, drawn in the Realist conventions of Dickens’ own writing. Against this is a more symbolic narrative – another layer, if you will – that draws upon history, but combines outwardly disparate ideas and sources cohesively through Flanagan’s own interpretative power. Already we have seen the skill by which he draws together the seemingly disparate stories of Arctic exploration and the plight of the Tasmanian Aborigines. And he further imbues his story with the pathos and drama of Dickens’ own personal life: his obsessive personality, his failing marriage and cruelty as a husband, his growing attraction to another woman and his obsession with the stage and acting, which will insert him vicariously into the drama of Sir John’s expedition and force him to address his own conflicted feelings.

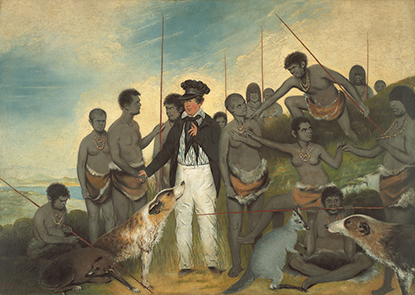

But against this drama lies an antithetical argument which is implied by the civilised/savage dichotomy. The child mentioned above who is “to embark on a rigid programme of improvement” is a little girl called Mathinna. Mathinna was also a real child and she is represented in a red dress in Thomas Bock’s painting. While it is Dickens’ story that drives the plot in England, it is Mathinna with whom we identify in Van Diemen’s Land. She is only eight or nine years old for most of the story and she is adopted by the Franklins during their stay in the colony. She is ultimately an amusement for Lady Jane; an instrument through which she might demonstrate her own worth and fill her own emotional void. Lady Jane is unable to bear children of her own. Yet despite her own natural desires she remains quintessentially English:

How, as she went on with her dreary litany, Lady Jane wanted to dress that little girl up and tie ribbons in her hair, make her giggle and give her surprises and coo lullabies in her ear. But such frivolities, she knew, would only ruin the experiment and the young child’s chances.

As ever, feeling, like passion, must be suppressed, this time in the cause of civilising education and the ‘experiment’ to see if it might work with a black child.

What matters most isn’t the endless iterations of this theme, but its antithesis which Flanagan skilfully suggests through the symbolism of the novel. The actions of key proponents of British civilisation – Franklin and Dickens – undermine the tenets of emotional represion through their inability to control their own actions and feelings. Dickens, for one, is slave to his own obsessions and passions which he cannot successfully sublimate through his acting. Sir John is a hapless individual who cannot control his own desires.

The matter is most clearly presented through Sir John’s growing obsession with Mathinna. He is a man deeply unsuited to the Governorship. He is a poor society host, he is out of touch with the colony and he mostly abdicates his authority to his wife. Of all the characters in the novel, it is Sir John who seems least effectual in the plot, yet is the most consequential symbol of British colonialism and paternalism. He names Mathinna ‘Leda’, which is ominous from the start. Leda is from Greek Myth. She is famously raped by Zeus who is disguised as a swan. In one variant of the story she lays two eggs from which four babies hatch: Clytemnestra, Castor and Pollux, and Helen of Troy. Leda gives birth to four of the cast of the Trojan War! Sir John initially begins to play with the young Mathinna, and engages her by participating in her game of trapping seagulls. But the connection to the original myth is completed when he rapes Mathinna dressed as a swan after a costume party: a rape with an allusion to Greek myth – how civilised! But its brutality, as an allusion to colonialism and exploitation, couldn’t be clearer. The myth of British restraint is dead and the exploitation and degradation of the Aboriginal race is pretty clear after that.

Wanting is an example of a sophisticated engagement with history by a contemporary author for whom that history is personal. A lesser treatment by a lesser writer might have produced a good dramatic account of the period in which the Tasmanian Aborigines were in decline due to war and disease, and that would have been fine and no doubt worth reading. But Flanagan has produced a narrative that is far more layered and engaging. There is so much that could be said about this book from other perspectives, or by focussing upon different aspects of the plot, its history or its characters. The story is rich in allusion, incident, insight and drama.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed Facebook

Facebook Instagram

Instagram YouTube

YouTube Subscribe to our Newsletter

Subscribe to our Newsletter

No one has commented yet. Be the first!