Under Milk Wood, set in the fictional town of Llareggub (read it backwards), Wales, evokes the life of the people of the town through the course of a day. Dylan Thomas sub-titled his work ‘A Play for Voices’. The play was originally commissioned by the BBC for radio, which explains the sub-title. However, Under Milk Wood was also filmed in 1972 by Andrew Sinclair, with Richard Burton as ‘First Man’, a part which replaces his role as First and Second Voices in the original 1954 radio play, and Peter O’Toole as Captain Cat. Elizabeth Taylor played Rosie Probert in the film, but her part is so small – Rosie is dead and only a memory of Captain Cat’s in the play’s present – that her headline credit for the film would be puzzling to anyone too young to remember that Burton, O’Toole and Taylor were major stars of that time.

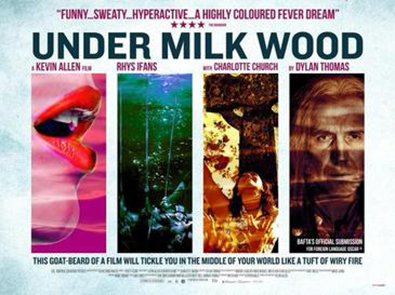

I’d like to start with a brief discussion of the film, particularly Burton’s part in it, even though this review is about Thomas’s play as it is written. In the original 1954 radio version Burton spoke the part of the First and Second Voices, which are a narrative role. In the film the role seems divided again, since First Man is accompanied by Second Man, played by Ryan Davies, as they wander about the town. Yet Burton, himself a Welsh actor (with his famous cultivated British accent), maintained the bulk of the narrative voice-over. Of course, a peculiarity of Sinclair’s approach to the material, was the oddness of two men walking about the town. Sinclair obviously felt a need to address this. At one point one of the town’s people makes reference to these two strange men walking about. Later, Sinclair offers some explanation of their presence by having them meet a woman, a prearranged meeting, and have sex with her in a barn. Their tryst makes sense of their presence, but by explaining the prosaic matter of his own staging, Sinclair detracts from the role of the narrative voice: to be a conduit by which the reader/listener experiences Llareggub.

This is why I think Under Milk Wood works better as a radio play, rather than a film. Notwithstanding some of the film’s other peculiarities, which I won’t discuss here, the role of First Voice and Second Voice is to draw the reader/listener into the world and lives of the people of Llareggub through the poetic idiom of the Voices, like a meditative, hypnotic trance that infuses our imagination with Thomas’s world. The play begins:

It is a spring, moonless night in the small town, starless and bible-black, the cobblestreets silent and the hunched, courtiers’-and-rabbits’ wood limping invisible down to the sloeblack, slow, black, crowblack, fishingboat-bobbing sea.

This is language tightly packed, evoking a moment: the dark of the night; its stillness. But it also appeals to our intellect through its play on the various iterations of ‘black’, coupled with the hypnotic rhythmic repetition that suggests the movement of the water, along with the sleep of the town’s inhabitants, through the lulling cadence of the speaker’s voice as it draws us into the play. The houses are “blind as moles” or as “blind as Captain Cat” who will soon be introduced to the reader/listener. The senses are muted, as they should be, since this is night. It is the sound of the Voice and its power to evoke – because it is the reader/listener who exists within the world entirely by the power of the speaker’s voice – that make this such a strong opening. But Thomas isn’t just evoking a scene here. He is positioning the reader/listener, who is encouraged to imagine themselves entering the scene. “Come closer now” we are urged. “Only your eyes are unclosed to see … And you alone can hear …” we are told as we contemplate the sleeping town. Thomas not only requires we listen to the dreams of Llareggub as it sleeps, but he wants us to enter them imaginatively: to ‘see’ them as vividly as blind Captain Cat, who sits in his house ‘watching’ the town, can ‘see’ by his attentive listening.

Under Milk Wood doesn’t rely upon a main plot, but it does have a simple structure – from the sleeping night of the town it moves to its morning and afternoon, and returns to night – and within that we have glimpses of the lives of the people of Llareggub. Our attention is directed here and there about the town by the First and Second Voice, and we begin to piece together a series of relationships and stories. In his dreams, Captain Cat is haunted by the memory of sailors who have died under his command, but at day he thinks of Rosie Probert, instead, whose love he once shared with other seamen, and who now remains in his memory as his most significant relationship. There is Mrs Ogmore-Pritchard, who obsessively cleans her house and lives with the memory of her two former husbands; she even imagines herself sleeping with the two of them as once. Mog Edwards and Myfanwy Price conduct a love affair through letters, separated only by the length of the town, itself. They will never meet. Meanwhile, Polly Garter and Mr Waldo have multiple relationships. Polly is developing a poor reputation in the town for having multiple lovers, but this is meaningless to her against the memory of her one true love, Little Willy Wee. Mr Waldo has had five wives (despite his now-corpulent figure) and is plagued by paternity claims. Polly Garter and Mr Waldo are eventually driven into each other’s arms, despite the disapproving rumours of the town, under the darkening sky in Milk Wood. There are dark obsessions within the town, too. Mr Pugh, who despises his domineering wife from across the dinner table, fantasises about poisoning her. Yet there is also lightness: Reverend Eli Jenkins begins and ends each day with a morning service and an evening poem which highlight his desire to promote culture within the town, as well as his abiding love for the town and its people:

- We are not wholly bad or good,

- Who live our lives under Milk Wood,

- And Thou, I know, wilt be the first

- To see our best side, not our worst.

Under Milk Wood is a layered work that seems deceptively simple. But it rewards a return read/listen. There are little details that amuse: the policeman P.C. Attila Rees, pees in his helmet, using it as a chamber pot while he is half asleep, and leaves home in a huff the next morning with a damp helmet. It’s a moment easy to miss on a first reading. Other details take on new significance as, like the rhyme of poetry, they begin to echo other moments in the play. For instance, Mrs Ogmore-Pritchard’s two dead husbands find their counterpart in the baker’s two real, living wives, Mrs Dai Bread One and Mrs Dai Bread Two. Meanwhile, there are relationships within the play that seem more significant upon consideration. Mog Edwards’s happily platonic epistolary relationship with Myfanwy Price is strange and joyous. “Come to my arms, Myfanwy” he urges, though we know they will never meet. Yet Sinbad Sailor, who loves Gossamer Beynon, finds he cannot openly declare his love while ever his grandmother, Mary Ann, still lives. His plaintive cry “… oh. Gossamer, open yours! [arms]” reminds us that in Llareggub there is the whole gamut of human experience.

Llareggub is a place fuelled by desire, joy, hatred and rumour. The rumours against Polly Garter are the stuff of small towns, but so too is their inaccuracy. When the butcher, Beynon, makes a joke over breakfast about what he is feeding the dog, the rumour that he is actually butchering dogs seems to spread with lightning speed through the grapevine. And the town seems alive with desire, both requited and unrequired, from the kissing games of the school yard, and the auto-erotic musings of young women, to the gone-to-seed lovers who have already suffered loss.

Besides the various relationships, both hopeful and thwarted, there are other peculiar tensions in the play. Time, for instance, seems both in movement and inert. The narrative voices draw us on throughout the day – “the morning school is over”, “Now the town is dusk” – yet there is a sense the Llareggub is caught in time. The voice of a Guidebook suggests the town has “some of that picturesque sense of the past so frequently lacking in towns and villages which have kept more abreast of the times”; the hands of the pub clock have been frozen in place for fifty years; and Lord Cut-Glass, who drives himself insane by surrounding himself with 66 clocks, represents a strange paradox, since none of his clocks can agree on the time, and some are missing hands, suggesting a temporal stasis.

All this is to suggest that while Under Milk Wood does not attempt to develop a single dominant plot, there are many small stories and ideas that have rich rewards for an engaged listener/reader. Llareggub represents a type; a moment in the social history of the Welsh people; perhaps evoking a national character. But also, human nature. There are so many aspects of the play to focus upon that even those I have discussed are only a selection.

If you are interested in Under Milk Wood I would suggest that you have access to the written play as well as a radio performance. There are several versions, but the one I used was 1954 BBC production with Richard Burton, updated in 1963 to restore a few passages omitted from the original broadcast. It deviates only slightly in one or two places from Thomas’ original text. And read/listen it several times. The experience of doing so is like getting to know people. You understand and ‘see’ more each time you obey the First Voice’s urging, to “come closer”.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed Facebook

Facebook Instagram

Instagram YouTube

YouTube Subscribe to our Newsletter

Subscribe to our Newsletter

No one has commented yet. Be the first!