Uncle Tom’s Cabin follows the stories of two slaves – that of the titular Uncle Tom and of Eliza. Both Tom and Eliza are owned by Arthur Shelby, a Kentucky plantation owner. Both are highly valued by Shelby and are treated well (as are all the Shelby slaves). But unfortunately for Tom and Eliza, Shelby gets into financial trouble and to save himself, agrees to sell Tom and Eliza’s son Harry, a young boy of around four years of age.

Tom has a wife and three young children, from whom he naturally does not wish to be parted. Eliza naturally wants to keep her son with her, and was indeed promised by Mrs Shelby that her son would never be sold away from her. But as slaves, neither of them gets a say on whether or not they can stay with their families. This start to the story shows one of the evils of slavery that Stowe is trying to convey in this novel – that it results in the dehumanisation of a group of people. As Haley, the slave trader, puts it, These critters ain’t like white folks, you know; they gets over things.

For example, he suggests to Shelby that the gift of a pair of earrings would be all Eliza would need to get over losing her son. This sentiment is later echoed by Marie St Clare who decides to bring her Mammy with her when she marries Augustine St Clare, forcing Mammy to leave behind her husband and children. Her response to St Clare’s northern cousin Ophelia’s suggestion that black people have immortal souls the same as white people gets this response:

But as to putting them on any sort of equality with us, you know, as if we could be compared, why, it's impossible! Now, St. Clare really has talked to me as if keeping Mammy from her husband was like keeping me from mine. There's no comparing in this way. Mammy couldn't have the feelings that I should. It's a different thing altogether, – of course, it is, – and yet St. Clare pretends not to see it. And just as if Mammy could love her little dirty babies as I love Eva! Yet St. Clare once really and soberly tried to persuade me that it was my duty, with my weak health, and all I suffer, to let Mammy go back, and take somebody else in her place.

The irony is of course that Mammy does love her husband and children whereas Marie cares for no one but herself. Marie thinks she treats Mammy well, as she gives her many clothes, has only had her whipped a few times and allows her to drink coffee or tea with white sugar in it. She even tried to find Mammy a new husband and could not understand Mammy’s refusal of this.

But I’m jumping ahead to talk about the St Clares, as they do not come into the story until much later.

Eliza overhears Shelby telling his wife of his decision to sell Harry, along with Tom, and decides to flee with him. She attempts to persuade Tom to run as well, but Tom, on hearing of Shelby’s financial problems, decides to accept his fate and calmly waits to be shipped down to New Orleans. Tom is deeply religious, and believes that he needs to remain loyal to his white master’s wishes, even if that means separation from his family. He is also motivated by concerns for the many other slaves on the Shelby plantation, all of whom would be sold if the plantation was sold. Tom’s selflessness and concern for others is frequently shown over the course of the book.

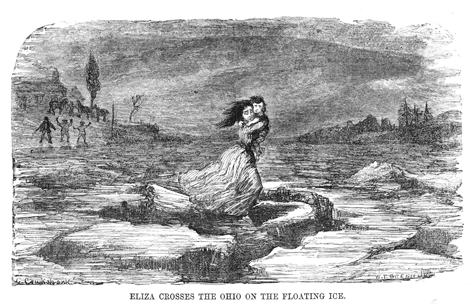

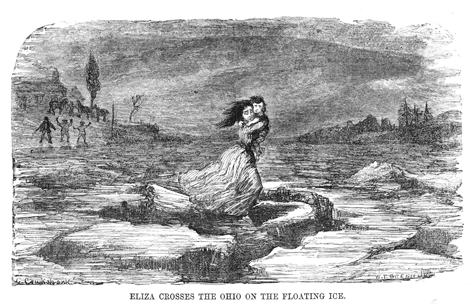

Eliza heads north towards Ohio, hoping to eventually make it to freedom in Canada. Her flight from the Shelby plantation and across the Ohio River is one of the most dramatic scenes in the book. Eliza makes it to the river only to find it still covered in ice floes, and no boats available to cross. She rests in a hotel in hopes of a boat soon, then has to run again when Haley arrives to reclaim her. In desperation, she leaps from the river bank onto the ice:

. . . nerved with strength such as God gives only to the desperate, with one wild cry and flying leap, she vaulted sheer over the turbid current by the shore, onto the raft of ice beyond. It was a desperate leap—impossible to anything but madness and despair; and Haley, Sam, and Andy instinctively cried out, and lifted up their hands, as she did it.

The green fragment of ice on which she alighted pitched and creaked as her weight came on it, but she stayed there not a moment. With wild cries and desperate energy she leaped to another and still another cake; stumbling—leaping—slipping—springing upward again! Her shoes are gone—her stockings cut from her feet—while blood marked every step; but she saw nothing, felt nothing, till dimly, as in a dream, she saw the Ohio side, and a man helping her up the bank.

This image is one of twenty-seven woodcuts created by George Cruikshank to illustrate the British serialised edition of the novel in 1852.

In looking online for an image of this scene, I came across the information that this scene was actually based on a true story from 1838, of a slave woman who crossed over the ice floes while carrying her baby, to make it to the safety of the Ripley shore.

Even though Ohio is a northern State, where there was no slavery, the Fugitive Slave Act of 1850 made it illegal to give any aid to escaping slaves. Therefore, Eliza needed to make it to Canada to be truly free, despite making it safely to Ohio. This reminded me of a plot detail in Margaret Atwood’s The Handmaid’s Tale, where people escaping the Gilead regime attempt to escape to Canada. I guess a neighbouring, independent country with a large border will always be an attractive destination for anyone fleeing the U.S.

While Eliza is fleeing to the north, Tom is shipped down river towards New Orleans. A young girl travelling on the same boat, Eva St Clare, falls into the river, and Tom dives in to save her. Eva’s father then buys Tom from Haley. Augustine St Clare is a reasonable and intelligent man who treats his slaves well. He actually recognises that slavery is wrong, but does nothing actively to end the practice. He argues about the morality of slavery with his brother (a plantation owner), but their arguments seem to lack any real passion and do nothing to change each other’s viewpoints. St Clare is held back from doing anything in part because he doesn’t believe that one man could make a difference. He is also intelligent enough to realise that just freeing slaves is not enough, that it would be cruel to free all slaves without having given them any education or other means of survival, and with society generally (northern as well as southern) prejudiced against them.

But, suppose we should rise up tomorrow and emancipate, who would educate these millions, and teach them how to use their freedom? They never would rise to do much among us. The fact is, we are too lazy and unpractical, ourselves, ever to give them much of an idea of that industry and energy which is necessary to form them into men. They will have to go north, where labor is the fashion, – the universal custom; and tell me, now, is there enough Christian philanthropy, among your northern states, to bear with the process of their education and elevation? You send thousands of dollars to foreign missions; but could you endure to have the heathen sent into your towns and villages, and give your time, and thoughts, and money, to raise them to the Christian standard? That's what I want to know. If we emancipate, are you willing to educate? How many families, in your town, would take a negro man and woman, teach them, bear with them, and seek to make them Christians? … You see, Cousin, I want justice done us. We are in a bad position. We are the more obvious oppressors of the negro; but the unchristian prejudice of the north is an oppressor almost equally severe.

Tom lives with the St Clare family for several years, until the sad death of Eva from tuberculosis. Augustine, though grieving for his daughter, starts to carry out one of her last wishes, that Tom be freed. But, before he can sign the papers, he is accidentally killed. All of his property, including his slaves, go to his wife, Marie. Marie is selfish and completely lacking in any sympathy or feeling for others. She didn’t even pay any attention to her own daughter’s deadly illness, let alone be capable of caring for the slaves she inherits. She arranges for most of them, except the ones she brought with her from her own family on her marriage, to be sold immediately.

This leads us to the final part of the novel, and the demonstration of the most evil of the slave owners represented. Tom is sold to Simon Legree, the brutal owner of a remote plantation. Legree boasts to a fellow traveller after buying Tom and a few other slaves that he doesn’t bother to treat his slaves well, or do anything for their welfare. He considers providing any care a waste of money, and treats all his slaves as disposable:

Well, donno; 'cordin' as their constitution is. Stout fellers last six or seven years; trashy ones gets worked up in two or three. I used to, when I fust begun, have considerable trouble fussin' with 'em and trying to make 'em hold out,--doctorin' on 'em up when they's sick, and givin' on 'em clothes and blankets, and what not, tryin' to keep 'em all sort o' decent and comfortable. Law, 't wasn't no sort o' use; I lost money on 'em, and 't was heaps o' trouble. Now, you see, I just put 'em straight through, sick or well. When one nigger's dead, I buy another; and I find it comes cheaper and easier, every way.

Stowe does not whitewash the evils of slavery in any way. She demonstrates that even the well intentioned, such as St Clare, do harm, and that the worst, such as Legree and Haley, are brutes who promote a system where humans are routinely whipped, beaten, worked to death, raped and murdered. She also shows how even those who seem to not be part of the system of slavery, so entrenched in the southern states at this time, are complicit in keeping the system going, such as the politicians who enacted the Fugitive Slave Act, and the bankers who trade in slaves on behalf of clients.

There is an overly religious feel to this novel, with an emphasis on the value of faith, and on the worth of following the teachings of the Bible. But in feeling there was too much focus on Christianity, I needed to remind myself that I was not the intended audience for this novel. Stowe was writing deliberately to promote the idea that slavery was wrong and should be abolished, and used religion as one of her main arguments. While some parts of the novel show that religion can be used to keep people enslaved, she also uses religion to show that slavery is against the principles of Christian love, and that laws should not be followed if they are against a Christian belief system.

There is an apocryphal quote attributed to Abraham Lincoln that says that Stowe’s book started the Civil War, and I can see that it would have been a highly effective tool in raising awareness amongst people in the northern states of the U.S. However, it is a sad comment on our modern world that although slavery is now illegal in every country on the planet, there are currently an estimated 45.8 million people worldwide living in slavery, in the form of human trafficking, servitude, child labour, sex trafficking, forced labour and debt bondage, and many people in Western society are completely unaware of this fact. Somehow though, I don’t think any modern novel would have the same power to lead to a groundswell in public opinion against this in the same way that Stowe’s novel did in the 19th century.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed Facebook

Facebook Instagram

Instagram YouTube

YouTube Subscribe to our Newsletter

Subscribe to our Newsletter

No one has commented yet. Be the first!