It is not always easy to say what prompts me to buy and read a particular book, as opposed to the thousands of others available. Given that this is the first John Green novel I have read, and given that he writes Young Adult fiction, a genre I tend not to read anymore, I thought I would begin this review by trying to identify what factors led me to choose this book.

It was a pretty uninformed choice.

First, there was the movie, The Fault in Our Stars. My son had wanted to see it (that sounds like a justification, so let’s just say I went to see the movie). As I watched it I realised it was structurally the same story as The Wizard of Oz. I know it doesn’t look like the The Wizard of Oz, but squint a bit and you’ll see it. Van Houten, played by Willem Dafoe, is the Wizard: he is secretive and irascible like the wizard; Hazel and Gus go to Amsterdam to meet him, like journeying to the Emerald city; he sends them away on a kind of quest; he’s really just a phoney; and he turns up in the end with a more humane demeanour. But the story was not derivative. Rather, I felt the movie suggested a teen writer who may have a literary bent.

Then there was the title of this book: Turtles All The Way Down. It reminded me of a story often repeated of an old woman talking to a scientist about the nature of the universe. While the scientist tries to explain how the universe works, the old woman maintains that the world sits on top of a giant turtle. When the scientist questions what the turtle sits on, she replies with all the certainty of belief: It’s turtles all the way down.

It wasn’t just this story, but the connection I made to Terry Pratchett, the English writer, whose famous DiscWorld novels are set in a world travelling atop four elephants standing on top of a giant cosmic turtle. Both Pratchett and the story of the old woman are referenced in Green’s novel.

Finally, it was all those copies sitting on the shelf in the bookstore. I’ve called this the Ikea effect in another review. One copy may be of no interest, but see fifty copies stacked seductively on the shelf, and you’re bound to be drawn in, not just by the look of the thing, but the thought that John Green must be a successful writer, must have some appeal, and there is a desire to find out what that is.

Apart from that I knew nothing about the book; nothing about its plot.

As I began to read I felt I detected a pattern. I know. My first John Green and I think I can see a pattern. Even as I write this I am imagining a die-hard fan gritting their teeth at my ignorance. But here goes. In The Fault In Our Stars Hazel has lung cancer. In this novel, Aza is beset by mental illness. She has obsessive thoughts and demonstrates compulsive behaviour detrimental to her physical wellbeing as well as her social relationships. Sure, that only covers two books, but a protagonist with debilitating and/or alienating social/mental/health problems seems pretty common in Young Adult Fiction. I may not have read much of it lately, but I’ve read my fair share. Coupled with that is the premise that these characters are being thrust into the adult world, whether it be to solve a problem the police can’t solve (another common trope) or because adults are absent or ineffective.

In this novel Aza lives with her mother and her condition is treated by Dr Singh. Her mother struggles to understand what her daughter is experiencing. Dr Singh is kindly but her attempts to help Aza seem to be proving ineffective. The absent adult is her father, now dead for several years, but present in the sixteen-year-old Toyota Corolla Aza drives, which she has christened Harold, along with her father’s old phone containing family photos. Her friend, Daisy, lives with her parents and sister, but we see little of them since the book is written from Aza’s point of view, and Aza’s condition means she is introspective and rarely asks about Daisy’s life.

Together, they decide to try to find billionaire Russell Pickett. He has disappeared. The police are after him for fraud. There is a $100,000 reward. Another absent adult. Aza re-establishes an old friendship with Pickett’s son, Davis, and they become romantically involved. Davis is trying to hold everything together for his younger brother, Noah. But their world is falling apart.

So, the novel follows a conventional teen plot. There are personal problems the protagonist must face, there are the first flowerings of romance, there are friendships to be negotiated and maintained, new opportunities to explore, a mystery to solve which the police can’t and a future to face.

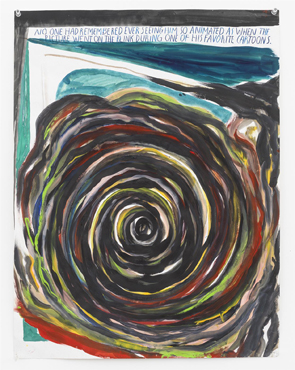

What sets this novel apart from a lot of teen fiction is the quality of the writing. Green’s book is well structured and employs various motifs which effectively draw the reader into the pain of Aza’s world, trapped by her own mind into harmful behaviours and thoughts. Several metaphors help to express this, including the endless spiral of her thoughts, represented by the Pettibon painting in Davis’s house, as well as the metaphor of the turtles, which is yet another endless spiral of thought. Aza’s compulsions centre around the question of self: around the impossibility of a single definable self and whether autonomous choice is even possible. These are big questions for a teen novel and Green chooses to explore this problem through Aza’s obsession with microbes and bacteria:

I started telling Davis about this weird parasite, Dilostomum pseudopathaceum. It matures in the eyes of fish, but can only reproduce inside the stomach of a bird. Fish affected with immature parasites swim in deep water to make it harder for birds to spot, but then, once the parasite is ready to mate, the infected fish suddenly start swimming close to the surface. They start trying to get themselves eaten by a bird, basically, and eventually they succeed, and the parasite that was authoring the story all along ends up exactly where it needs to be: in the belly of the bird.

Aza is obsessed with the thought that she lacks autonomy: that she is fictional; that her life is written and predetermined by her genes and the bacteria that swarm in her body. It’s an interesting thought for a teen audience when presented by a fictional character in a well-written novel. It’s cause for pause and reflection.

Her feeling finds reality when she realises she is indeed being represented in fiction. Daisy writes Star Wars fan fiction on the Internet and her stories chronical the love affair between Chewbacca and Rey. (In another fourth wall breaker, it’s interesting Green has given Daisy the name of the actor who plays Rey). This rather strange interspecies match may suggest something about tolerance or – something – but of real import is the side character Ayala, who constantly causes problems and alienates others. Aza comes to realise that Ayala is her in Daisy’s fictional universe. It causes a moment of tension between Daisy and Aza, and gives a reality to her existential threat, but Daisy’s story also represents the possibility that Aza might have a more hopeful future when Ayala becomes a hero in the stories.

The universe, itself, is also a prominent motif in the story. Davis is an amateur astronomer. His family’s wealth has allowed him to indulge this interest. Stars represent the past for Davis, since their light takes so long to reach earth that looking into space is effectively looking into the past. It is no accident that his favourite star, Tau Ceti, is twelve light years away. The light now visible represents light that began its journey before the death of his mother. Green also connects his characters through metaphor. Stars are not just old, but on a cosmic scale they form spiral galaxies, the very shape that represents Aza’s tightening, self-destructive thoughts.

One aspect of this story – and many teen stories I guess – is that the characters seem somewhat unrealistic. They are both burdened by terrible afflictions which often represent the alienation felt by many teenagers, as well as being gifted with great intelligence and talent. Daisy is a talented writer with a fairy tale success on the Net. Aza is highly intelligent and able to articulate her problems in ways readers of the novel most likely would aspire to. Mychal, Daisy’s boyfriend, is an aspiring artist who is just having his first exhibition of art. Davis is wealthy beyond imagining as well as humane and well-adjusted, despite his family’s terrible problems. He is also highly intelligent. He has an understanding of astronomy which affords him acute personal insights. And if this isn’t enough, he also writes and reads poetry. Yeats’s ‘The Second Coming’ provides yet another spiral metaphor – the widening gyre

by which he is connected to Aza.

In fact, Green’s novel is littered with literary references, which made me think that that my first impression I received from the movie was correct. Green references or quotes Pratchett, James Joyce, Shakespeare and others. His world is defined through art and science, and therefore wholly secular in its approach to its philosophical questions. But while Green’s universe never makes room for religion or God, his characters seem to live a destiny, sometimes oppressive and threatening, at other times reassuring, represented by ideals of science and art. They are able to make sense of their world on a level beyond many of Green’s audience.

Turtles All The Way Down is a simple story with many familiar teen tropes, but it is well written novel with philosophical pretensions that work effectively. It’s an easy read and worth a look.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed Facebook

Facebook Instagram

Instagram YouTube

YouTube Subscribe to our Newsletter

Subscribe to our Newsletter

No one has commented yet. Be the first!