Tragedy at Law reminded me very much of the story of Marcus Einfeld, a former Australian Federal Court Judge. Einfeld had a distinguished legal career and had received many honours. But in 2006 he received a speeding ticket for driving 10 km/hr over the speed limit (6 miles/hr), as recorded by a speed camera. The fine was only $77, but he contested the ticket in Court, to avoid the additional penalty of a loss of three of his remaining four points on his licence. In Australia, a loss of twelve points results in a loss of licence. He claimed in Court that he had loaned his car on that day to an old friend who was visiting from the US. He gave evidence under oath and signed a statutory declaration. The magistrate dismissed the charge. Most people wouldn’t have paid any attention to such a minor incident. But a reporter discovered that the old friend Einfeld claimed had been driving his car that day had actually died three years earlier. After the story broke there was a police investigation and Einfeld made a detailed but false statement to the effect that the driver was another woman with the same name as the woman originally identified. He was arrested and eventually tried for perjury and perverting the cause of justice. He was found guilty and sentenced to three years imprisonment. He was subsequently stripped of all of his honours, including his Queen’s Counsel commission and the Order of Australia. It was an ignominious end to a distinguished career, all because he lied to get out of a trivial speeding fine.

Hare’s story, Tragedy at Law, centres on a self-important High Court judge, Mr Justice Barber, as he travels from town to town presiding over the southern England Court of Assizes. Early in the book Barber drinks too much at a dinner and accidentally knocks down a pedestrian while driving back to his hotel. The man it seems is not seriously injured: he has sustained only slight damage to one finger. But the judge, being a busy man and above day to day trivialities, had forgotten to renew his driver’s licence and his insurance. Local authorities hush up the minor incident, thinking it best not to publicly bring disrepute on the Court. Barber is resigned to having to pay a settlement to his victim in compensation for the injury, but doesn’t think it will be too much. Unfortunately for him, the victim is a renowned concert pianist and the damage to his little finger will likely end his career. The damages claim is much higher than Barber had anticipated and the amount will ruin him financially. But if he doesn’t pay the amount claimed, the victim has the right to bring a writ against him in Court, an action that will end Barber’s career on the bench, anyway. You can see why I immediately recalled the Einfeld case, a minor driving offence that spirals into a scandal.

This story runs as the background all through the story. But in addition to that, Barber has been receiving anonymous threatening letters. And then various attempts on his life begin, starting with a box of poisoned chocolates sent to him in the mail. It seems the Judge’s life is in danger, but he refuses to take the threats too seriously. To him, this public threat of physical injury is less important than the private threat of financial ruin and professional disgrace that he is desperate to keep under cover. It adds up to an enthralling story as we follow Barber’s progress with the Assizes circuit around southern England, wondering which of the threats will finally eventuate to destroy him.

Cyril Hare was the pseudonym used by Alfred Alexander Gordon Clark, a distinguished lawyer who practised as a barrister and served in various legal and judicial capacities, and as a county court judge. He was very familiar with the Assizes and creates a very authentic atmosphere in his story.

There’s not actually a lot to the mystery; in fact we don't get an actual murder until very late in the book. I identified the villain fairly quickly and despite not having any familiarity with the British penal code of the era, I even came close to identifying the motive. But as with many of these classic mysteries, it’s not all about the story. Hare is a witty writer, and his portrayal of the self-important judge and the elaborate ceremony around the Assizes are just plain amusing to read.

And again, the book highlights a few aspects of the society at the time. For example, the Judge’s wife, Hilda, is a qualified lawyer and quite brilliant in some areas of law. But she has never been able to practice, as females were not seen to be suitable candidates for the legal profession. Hilda’s legal abilities far exceed her husband’s, but she has had to content herself with assisting him behind the scenes and propelling him to take silk and eventually ascend to the bench when she would have been so much better at the role. We frequently see her over the course of the book pointing out fallacies in various barrister’s arguments and drawing the Judge’s attention to relevant case law. What a complete waste of her talents! And this book was set in late 1939, in the early days of the war. There are occasional comments about the lack of qualified people for many positions, with so many men enlisted in the army, but it doesn’t seem to register with the authorities that they are leaving a huge resource untapped by not acknowledging the ability of women like Hilda.

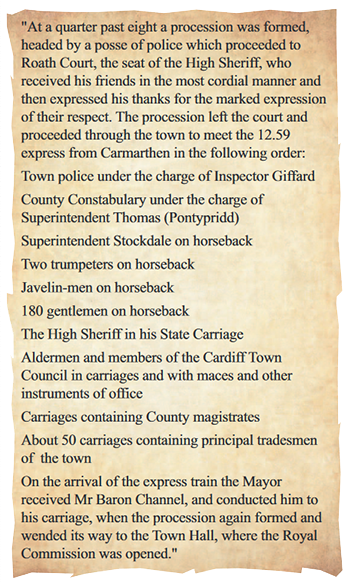

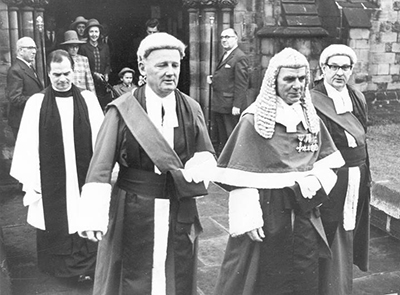

A further thought on this being set early in the war: it’s incredible to think that the level of ceremony described by Hare was kept up at this time, with a formal procession of the Judge through town to an opening ceremony at the Cathedral before they continue to the Assizes, with the whole entourage including a High Sheriff, an Under Sheriff, the Judge’s Clerk, the Judge’s Marshall, the Judge’s Butler and the Marshall’s Man, all protected by the Chief Constable of the City and the county Superintendent of Police. But there have been some concessions to the war: the Judge mournfully notes the lack of trumpeters heralding his procession. From a modern perspective it seems like Hare has portrayed something from medieval times, but it isn’t actually that far back in our history that these grand rituals were used to give a visible representation of the power of the law. The Assizes system continued in England up until 1972.

The back cover blurb on my copy of the book suggests that Francis Pettigrew, a barrister, is the main character in this book. Unfortunately, this is misleading. Pettigrew is not the major focus of the story, and is actually one of the suspects due to his history with the Judge and his wife. Most of the story is told from the point of view of the Judge’s Marshall, a young idealist who believes in the Law and is disappointed that the drink driving incident has been hushed up. Hare had actually been a Marshall on an Assizes circuit during the war, so he intimately knew the world he was portraying in this book. Pettigrew, however, is a fantastic character, and he provides most of the humour in the story, with his cynical attitude and his sarcastic comments. And he is also the one who finally grasps the obscure legal point the case turns upon, so he does have a major role at the end.

Hare was a writer I had never heard of before I started on my targeted reading of Golden Age writers. Hare is another writer I now intend to read more of, when I can find his books. This one is highly recommended.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed Facebook

Facebook Instagram

Instagram YouTube

YouTube Subscribe to our Newsletter

Subscribe to our Newsletter

No one has commented yet. Be the first!