If you read reviews (and perhaps you do because you’re reading this) you’ve no doubt read that certain books will have you in tears or others will have you laughing out loud. I admit that I have smiled, on occasion, when reading a funny book. If I laugh, however, it is usually a silent internal laugh; a personal appreciation that that was funny. But with Percival Everett’s The Trees, a novel set largely in Mississippi which addresses entrenched racism in American society, I found myself laughing out loud without meaning to on more than one occasion. Most embarrassing was on a silent train carriage on my way home from Sydney. I burst out laughing and disturbed everyone.

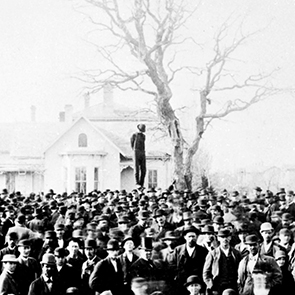

And what subject could Everett have chosen as the basis of a novel funny enough to have had me chortling: the historical lynching of black Americans and a series of gruesome murders with seemingly no rational explanation, no less. It’s a subject that is not funny, per se, and may turn some people off from the start. So let me say that if you like crime novels, this is a crime novel with a twist, as well as being a satire on racist values which have been enabled by Trump, both during and after his presidency. The book has a political edge, but it carries its political trappings lightly in a plot that is well-paced and a story that is page turning. It helps that the chapters are short. A long chapter for this book is three or four pages. Many are one or two pages. One is only a sentence. There is no fat in this story. When we meet Wheat Bryant and his wife Charlene, Granny Carolyn and her nephew Junior Junior in the first chapter (“His father, J.W. Milam, was called Junior, and so his son was Junior Junior, never J. Junior, never Junior J., never J.J., but Junior Junior”) it is reasonable to expect we’re going to get to know the family more in succeeding chapters. But Junior Junior is already dead by the beginning of the second chapter and Wheat isn’t long in following him.

There will be other murders, but this is the start. And this series of murders has a bizarre twist. To begin with, a Black man is found dead beside the body of a White man – Junior Junior and then Wheat initially – holding their testicles, torn from their bodies. Is the black man also a victim? What is the circumstance leading to this strange tableau? But more puzzling, how does the Black victim (perpetrator?) who seems to have been dead – “most sincerely and really dead” – disappear after police have examined the scene and bagged the bodies, and then turn up at the next murder scene holding the testicles of yet another victim, just as dead as he appeared to be before?

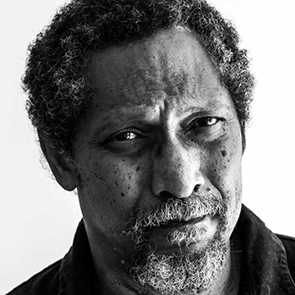

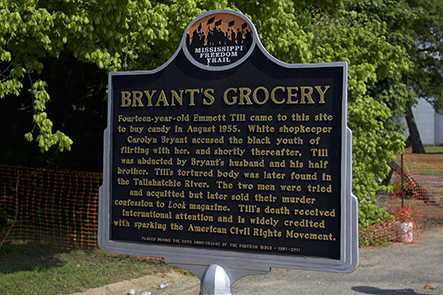

The premise is intriguing enough on its own, without the latent implications suggested by the crimes: of the reversal of power between White and Black Americans; of the mythic sexual propensity attributed to Black men and the emasculating power of the crimes. Everett is tapping atavistic racial fears that belie the myth of a pluralistic modern America. Because it quickly becomes apparent that the motivation for the crimes may be revenge for historical violence against Blacks. Granny Carolyn, it turns out, falsely accused Emmett Till in the 1950s of speaking suggestively to her, and it was Roy Bryant and J.W. Milam, the fathers of Junior Junior and Wheat, who killed him for it. In this, Everett has chosen to intersect his fiction with reality. Emmett Till was a fourteen year old boy murdered by Bryant and Milam in 1955 after Till was accused of flirting with Carolyn Bryant in her grocery store. They mutilated him, shot him and dumped his body in the Tallahatchie River. The men were acquitted by an all-white jury, but their guilt is not in doubt. They later sold their story to Life Magazine, admitting to the murder since they were protected by the law of Double Jeopardy. Interestingly, it was long thought that the men had castrated Till before killing him, but a 2005 exhumation of his body showed that not to be true.

None of this would seem to be the basis for a funny book, but Percival Everett is skilled at highlighting the ridiculous, the craven, the mendacious and irrational tenets of White supremacy and making us like the humorous repartee of his Black characters, primarily three investigators sent to oversee the increasingly widespread and bizarre circumstances of the murder: Jim Davis and Ed Morgan of the Mississippi Bureau of Investigation, and later Special Agent Herberta Hind of the FBI. Naturally, the Southern police are none too happy at the implication of Federal oversight – that they can’t handle their own crime scenes – but it is worse because all three agents are Black. Everett’s Black investigators are smart and witty, with a healthy level of smart-arsery levelled at the Southern White police with whom they must work.

Whites with racist attitudes are generally portrayed as stupid with something ugly about their characters. A gross scene in which Charlene has her back pimples popped comes to mind, or Fancel, the horribly obese wife of Doctor Reverend Cad Fondle, who blames Obamacare for not solving her weight problem as she consumes pizza and beer on the couch.

Her husband’s name highlights another aspect of the book. Everett is a playful writer and he seems to delight in joke names. Fondle’s name suggests sexual impropriety. Charlene is known to her children by the sobriquet Hot Mama Yeller, after her CB handle – she is having an affair with a truckie – and by a stroke of logic she has named her son Triple J, since his father, Junior Junior, had two Js to his name. And there are other duplicate names. One victim is McDonald McDonald, and the name of another body is discovered to be Mr Gerald Mister: Mr Mister. Sometimes the names suggest something about character, like Fondle: often they are jokey for comedic effect only. It’s part of the pleasure of the book. Like spotting Easter Eggs, it’s fun to identify them.

Nevertheless, the novel does have a serious point to make and names are an important part of that, too. Gertrude, a waitress at a local diner, introduces Morgan, David and Hind to her great grandmother, known as Mama Z, who has kept a record of lynchings in the South ever since 1913, the year her father was lynched. She has collected over six thousand names in her files, along with the circumstances of each death. Everett devotes whole chapters to the listing of names belonging to black people killed by lynching. Like Emmett Till, it is another point at which Everett’s story intersects with reality. Yet the lists are not just clumsily inserted into the narrative. Everett makes the reality of their deaths a key part of the story. Naming them, we find, is crucial.

Of course, other aspects of the novel also intersect with reality in serious ways and they are interesting to consider. Some are subtle and need to be teased out in the mind of the reader. A good example is a couple of references to Elvis Presley and his home, Graceland, which seem to represent a counterpoint to Martin Luther King and the Lorraine Motel where he was murdered in 1968. The connection is understated in the story, but it is worth highlighting the dichotomy of two different world views that this represents. Presley was a Southern White American whose style was upheld as an alternative to Black artists. He sang sympathetically to the tenets of White Southern America: “I wish I was in a land of cotton / Old times there are not forgotten”. King was a black pastor who dreamed of a new future where everyone was equal.

But it is important not to say too much more about this great book which has some fun surprises. I thought as I read it, that people who like Jordan Peele’s 2017 film Get Out will appreciate what Percival Everett has done with the detective genre here. And there is just enough of Trump in the story to make the point about racism and modern America without burdening the plot with that man. I have to admit, it was one of two main scenes with Trump that made me laugh out loud on the train. Oh, and I loved the ending. I love love loved the ending. Even if it doesn’t hit you immediately, it will. Percival Everett is such a clever writer! How have I not come across him before when he has written so many books? How have the Sydney bookstores no other titles from his work, other than this book? He deserves more attention. This book would be a good place for you to start giving him that.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed Facebook

Facebook Instagram

Instagram YouTube

YouTube Subscribe to our Newsletter

Subscribe to our Newsletter

No one has commented yet. Be the first!