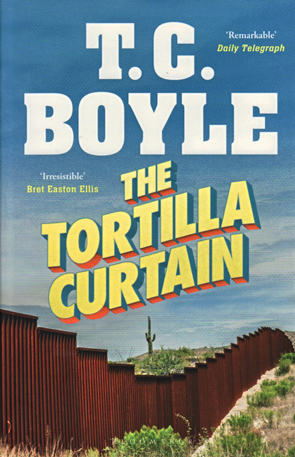

T.C.Boyle’s The Tortilla Curtain addresses the issue of illegal immigration at America’s southern border. Donald Trump made it a cornerstone of his 2016 election campaign. He promised to build a wall at the border with Mexico to stop illegal immigration. Europe is facing similar immigration issues with the Syrian conflict and other refugee crises. In Australia, the problem of illegal boat landings has shaped Australian politics since the turn of this century. Tough laws that refuse entry to refugees making illegal boat crossings from Indonesia to Australia have been justified on humanitarian grounds; there have been drownings in the past. Four years ago, in Europe, the dangers faced by those seeking asylum was highlighted by the picture of the small boy, Alan Kurdi, who was found drowned on the Turkish shore. Now, only last week, Oscar Alberto Martínez and his 23-month-old daughter, Angie Valeria, were also found to have drowned in their attempt to cross the Rio Grande from Mexico to America. In The Tortilla Curtain, Boyle puts a human face to these issues by telling the story of a privileged American couple, Delaney Mossbacher and his wife Kyra, living in a wealthy Californian housing estate near the Mexican border, and Cándido Rincón and his young pregnant wife, América, who cross the border illegally, looking for work and a better life.

What is immediately interesting about Boyle’s novel is that it was not written as a reaction to the current immigration problems faced by Western countries. The book was published in 1995, reminding us that the seeds of Trump’s campaign and the backlash against southern immigrants were sown long before Trump made a tilt at the White House. There has been much handwringing about how Trump has changed the moral tone of the United States, but Boyle’s novel reminds us that leaders tend to be a product of the zeitgeist rather than its progenitor. Following Tolstoy, who rails against the Great Man theory of history in his assessment of Napoleon at the end of War and Peace (how can one man hope to control the thousands of incidents that lead to victory or defeat once a battle has started; how can one man do anything else but ride the wave of history) it is possible to judge Trumpism as symptom rather than the disease.

Safety. Self-protection. Prudence. You lock your car, don’t you? Your front door? Delaney, believe me, I know how you feel. You heard Jack Cherrystone speak to the issue, and nobody’s credentials can touch Jack’s as far as being liberal is concerned, but this society isn’t what it was – and it won’t be until we get control of the borders.

This is an important aspect of Boyle’s novel, which in the best realist tradition writes large issues onto the smaller map of ordinary individual lives. Both Delaney and Cándido are ordinary men attempting to live good lives within the parameters of their own socio-historical contexts. Delaney is a nature writer and his wife, Kyra, is an ambitious real estate agent, selling luxury homes to the well-heeled. Cándido has taken his second wife, América, now pregnant with their first child, and has crossed the border illegally in the hope of a better life. But events are outside the control of either man. Delaney accidentally hits Cándido with his car. He is horrified, of course, but Cándido seems okay (in fact, he is badly injured) and Delaney sends him away with a twenty-dollar bill as a salve to his own conscience. Delaney remains bothered by the incident, however, and as pressures rise within his community to take action against illegal immigrants – first a manned gate and later a wall – his own liberal humanist ideals are worn down to a racist, obsessive and finally violent nub.

This isn’t about coyotes, don’t kid yourself. It’s about Mexicans, it’s about blacks. It’s about exclusion, division, hate.

Cándido, likewise, is worn down by his experiences, as he tries to find work, provide for his pregnant wife, deal with his injuries, deal with thieves, with fire and the constant threat of being caught and deported by La Migra - the Immigration. Boyle captures Cándido and América’s predicament not only through their endless privations and setbacks, but through literary allusion and imagery which characterise different perspectives of the Mexican immigrant. Cándido likens himself to Job, beset by misfortune, or Christ in his Passion, and fails to understand why he suffers. From the perspective of white America, however – through Delaney’s unwitting comparison to Mexicans with Coyotes – Cándido and his like are nothing but pests:

Coyotes, gophers, yellow jackets, rattlesnakes even – they were a pain in the ass, but nature was the least of their problems. It was humans they were worried about. The Salvadorans, the Mexicans, the blacks, the gangbangers and taggers and carjackers . . .

Southern illegal immigrants are a threat against the idyllic world of Delaney and Kyra and their like. Delaney and Kyra have lost a much-loved pet to a coyote which has climbed their chain link fence. Their response is to build a higher fence, but when that also fails to deter the predator and a second dog is snatched, the logical progression from private fence to community wall is not hard to make, despite Delaney’s public stand. The coyote is coming,

Delaney writes for his nature column, summoning his latent xenophobic angst to dramatize his portrait, breeding up to fill in the gaps, moving in where the living is easy. They are cunning, versatile, hungry and unstoppable.

Wall the place in. That was exactly what they intended to do.

What the novel captures is the physical and moral decline of each man. Cándido is beset by bad luck and exploitation, driving him and América further and further to desperation, wearing down his moral inhibitions and dignity, to the point that the imperative to save his family almost drives him to a feeling of contempt for white America, along with a loss of his own better humanity. For Delaney, his sense of helplessness is created by a siege mindset, making him capable of racist violence against all reason, good sense or even evidence. The calls for a gate outside the estate, Arroyo Blanco (White Stream), then for a wall, not only anticipate contemporary America, but characterise the problem not as a humanitarian crisis but as a war. The wall is defensive, houses are castle keeps and illegal immigrants are the army seeking to invade new territory. Given this thinking it is reasonable that both Cándido and Delaney should be judged not as individuals but products of their society and time; that neither man is inherently malicious or a failure, but both are driven, like Napoleon on the great tide of history, to positions that their better selves might repudiate. Boyle makes the point fairly clearly in a scene in which the residents of Arroyo Blanco Estate are briefly evacuated from their homes because of a fire. Kyra, fearing their house will burn, reveals her fears to Delaney: Where are we going to live?

The dramatic irony is palpable, given the privations of Mexicans just beyond their wall. But the drama is given greater existential import a few pages later as the residents face a night outside: They were out here in the night, outside the walls, forced out of their shells, and there was nothing to restrain them.

The moment highlights the thin veneer of civility, recalling Marlow’s dark musings on the deck of the Nellie as he rides at anchor with his companions on the Thames, and reminding us of the exigencies to which people like Cándido and América are subject, and the dark potentials of humanity.

I think it’s no accident that Boyle’s title recalls the Iron Curtain of the Cold War. Except, where Europe was once divided by ideology, The Tortilla Curtain returns to an era in which people are segregated by race and wealth. This is not, strictly speaking, Trump’s America, but the novel is as relevant and insightful as it might have been had it been published this year.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed Facebook

Facebook Instagram

Instagram YouTube

YouTube Subscribe to our Newsletter

Subscribe to our Newsletter

No one has commented yet. Be the first!