The Tale of Genji is reputed to be the first novel, written sometime during the Heian period of Japanese culture, roughly a thousand years ago, by a court lady known to us now as Murasaki Shikibu. The Heian period was characterised by a growing influence of Japanese literature and art as Chinese influence began to fade. Culture, art, poetry, even handwriting, were key indicators of education and refinement, during the period. The work is peppered with short poems used to communicate to lovers or other members of court, known as Tanka, which are emblematic of the refined culture of the court. Tanka was a form of poetry written to a strict syllabic rule over five lines, although Kenchō Suematsu, the translator of this work, renders them as four line poems in iambic tetrameter. These poems were considered a mark of one’s education and refinement. The poems often alluded to known literature to reshape and shade meaning, or cleverly played upon circumstance or symbols to imply an intention, or make a reply, while avoiding crass explication. When Genji flirts with his mistress’s maid in the garden, for instance, he makes his desire for her known through a Tanka:

- The heart that roams from flower to flower,

- Would fain its wanderings not betray,

- Yet ‘Asagao’, in morning’s hour,

- Intends my tender wish to stray.

Genji alludes to their floral setting to suggest his desire is like a wandering insect unable to overcome its own nature. ‘Asagao’ may refer to a garment worn by women when they rode, suggesting the stirring of his desire.

Mirasaki Shikibu was a member of this courtly world. She belonged to the Fujiwara clan. Having married into the royal line, the Fujiwaras had extensive influence in the court – in fact they wielded much of the power in court – and were even able to influence the royal succession. The Tale of Genji is a product of this period of history and the Heian court. As such, much of the world and even the values expressed in the story will be foreign to us. Genji is a window into a world now lost, through the pen of a woman who was at the centre of that world.

The Tale of Genji is the story of Prince Genji, son of the emperor and a lady of low status in the court, Kiri-Tsubo-no-Kōi, who dies in Genji’s infancy. Genji, gifted with looks and talent, has no court patron, but is favoured, nevertheless, by the emperor for the hand of Princess Aoi over the heir-apparent. The Tale of Genji is an account of Genji’s personal history: of his time in court, his various liaisons with women of the court, his eventual exile and his triumphant return.

That outline, of course, applies if you read this version of Genji. Kenchō Suematsu’s translation was the first translation of Shikibu’s tale into English. It appeared in 1882 but it included only the first 17 of 54 chapters. Later translations have included the entire tale, although the next major translation by Arthur Waley, which was originally published in six volumes from 1925 to 1933, mysteriously omitted one of the fifty-four chapters. Edward Seidensticker (1976), Royall Tyler (2001) and Denis Washburn (2015) have all produced complete translations. Seidensticker’s has a reputation of being most accessible. Tyler is thought to be closest to the original, but less accessible to the general reader, while Washburn is faithful to the original, but I have read criticism of his excessive explanations within the text.

One of the difficulties that will be encountered to varying degrees by modern readers, depending on which translation of Genji they choose to read, is the dearth of names in the story. Many characters are referred to generically – ‘a woman’ or ‘princess’ for example – and assume names according to their social position or even derived from locations with which they are associated. Murasaki Shikibu is almost certainly not the author’s real name, for instance. It either represents her status in court, or it may be derived from a major character who appears later in Genji beyond the bounds of Seumatsu’s translation. This is also the case with the Lady Wistaria (otherwise Princess Fuji-Tsubo), a woman who resembles Genji’s mother. She takes her name from the chamber assigned to her in the palace. The problem of naming becomes further complicated because some characters ‘names’ change according to their changing rank or position. Genji’s brother-in-law is a good example. Early in the story he is Kurando-no-Shō, but when he is promoted to Chūjō, a general of the Imperial Guards, according to Suematsu’s footnote, we come to know him as To-no-Chūjō, which describes his post. Late in this version of the tale his rank changes again and he becomes Gon-Chū-nagon. The reason for this confusing nomenclature resides with the culture of the Heian court, where it was impolite to name people directly. But the logic of it also means that we, as modern readers, can face some confusions, since there is the potential that we may encounter a new character bearing the same epithet as a character we have previously known by the same ‘name’. I think Suematsu makes these difficulties clear enough through his footnotes and bracketed asides which do not appear to be a part of the original text. For those interested in a complete translation of Genji, Tyler’s faithful adaptation of the original is said to preserve the ambiguities in nomenclature from the original, which is why it is considered a more challenging read.

With regards to the story, itself, the obvious point here is that the story arc I have outlined above, based upon Suematsu’s translation, is only a fragment of the complete work. Which raises an obvious question: why read this translation?

I’d like to offer a few reasons of my own as to why I decided to read this translation, even though I haven’t read a complete translation, yet (I have Tyler and Washburn’s translations on order, due in the next week or so). I decided I would read Suematsu’s translation even though I eventually intend to read a complete translation because, first, it is now a part of the history of the tale as it has been received by the English speaking world. Suematsu’s translation is considered to be somewhat dated now, but it is entertaining none-the-less. Suematsu was born in Japan and emigrated at the age of twenty-two to live in England. He lived there for eight years and graduated from Cambridge University, where he studied language, law and literature. There were no former translations of Genje which he could consult, and his translation is sometimes marked by nineteenth century idioms. It is also difficult to tell while reading him whether some scenes involving sexual matters have been sanitised, or whether they accurately reflect the tone of the original. Yet, despite some aspects of the translation feeling a little dated, it is still a highly readable version.

In addition to this, Suematsu’s version is probably a good place to start if you simply want to get a sense of the work. I am personally not a fan of reading abridged literature, particularly if it has been done by excising nearly three quarters of the original work (Suematsu may have originally intended to publish the complete tale in parts as Waley (almost) did.) Yet Suematsu’s version can still offer a sense that one is reading a complete work because he ends his translation at a point where a story arc is completed and major themes are addressed. Genji retires to Suma in exile after he is found with the younger daughter of U-Daijin, head of a powerful Japanese family who have already had their son elevated to the role of emperor. U-Daijin’s wife is determined to have her revenge on Genji, so Genji decides it is politic to retire from court life voluntarily before he is formally ousted. In Suma, Genji’s retinue is much reduced. He finds himself conversing with people ranks lower than he would normally entertain. And he struggles to find purpose in his life. When he is finally recalled by the emperor, his return to Japanese society is triumphant, while the emperor’s mother is frustrated in her attempts to have her revenge upon him.

This story arc seems satisfactorily complete because Shikibu’s opening chapters establish themes that are addressed in the final chapter of Seumatsu’s translation. In the first chapter, Shikibu introduces the notion of the transitory nature of our lives with the death of Genji’s mother, while in the second, the role of women as lovers and wives is raised in a conversation between Genji and his friends.

As the story begins, Genji has already been removed from the line of succession for political reasons. After his mother’s death he is given to his grandmother to raise, but his world seems precarious once again when she, too, dies. Genji is raised in court, but there seems an ever-present threat from political families who wish to promote their own children, particularly the mother of the heir apparent to the throne, who is jealous of Genji. In short, life seems uncertain. Fortunes may rise or fall, which is a fact articulated in Genji’s discussion about women in chapter two:

But how do you define the classes you have referred to and classify them into three? Those who are of high birth sink sometimes in the social scale until the distinction of their rank is forgotten in the abjectness of their present position. Others, again, of low origin, rise to a high position, and, with self-important faces and in ostentatious residences, regard themselves as inferior to none. Into what class do you allot these?

The second chapter establishes another major theme that dominates this section of Genji: concerning the different kinds of women and how they might make a man happy, or not. Modern sensibilities might be riled by the presumptive judgment Genji and his friends express about women, but we have to remember the age of the work and the culture it represents. We read Genji as a window to another time and place. Sama-no-Kami, a friend of Genji’s, defines women by their status, which he does not believe is fixed, but fluid. This is a subject reflected by the fates of several women throughout the course of the story, who either rise or fall relative to their associations with powerful men. The residence of Princess Hitachi becomes “desolate and wild, the mugwort growing so tall that it reached the veranda.” Princess Hitachi even seems to age prematurely, compared to Genji. His life is of the world and the court, and his associations with women are fluid. The princess’s life languishes as Genji forgets her, and she is only restored to some semblance of social dignity when he chances upon her house one day and remembers it. He undertakes to restore her and her dilapidated house to their former status. Princess Hitachi’s refusal to sell her home, which would have been of benefit to her, in the hope that Genji will one day return might seem pathetic to modern readers. But her decision is also a representation of another of Sama-no-Kami’s dictates: that the personal quality of a woman can transcend her social status. Hitachi is subject to the vagaries of the world, but from the perspective of her social milieu, she has maintained her status despite her troubled times.

Sama-no-Kami’s discussion about women in chapter 2 also focusses upon the personality types that can either enliven or burden a marriage: of women too engrossed in domestic perfection; of women who hide their feelings too much; of wives too critical of infidelity; or of wives too forgiving of infidelity. Despite this traditionally patriarchal discussion, Shikibu displays evidence of a scent of a modern thinking in her writing. As much as Sama-no-Kami may lecture his male companions on women, we discover his advice is coloured by his own failed relationships, first to a girl whom he could not successfully press to accept his infidelities, and second, to a girl whom he could not persuade from her own.

The subject of relationships extends throughout the story of Genji. Genji is unhappy with his wife, Aoi, and openly pursues other women. He has been inspired to experience their variety: “since he had heard the discussion about women, and their several classifications, he had somehow become speculative in his sentiments, and ambitious of testing all those different varieties by his own experience.” Genji sometimes has the whiff of a Casanova or Don Juan. Some of his pursuits end in sexual conquest, others do not. There is also the matter of Violet, a young girl of about ten, whom Genji takes from her father to raise. This is clearly an outrageous action by modern standards but one hard to judge from the social context. Is Genji predatory? – “If she is thus fair in her girlhood, what will she be when she is grown up?”, Or is he protective? – “I, too, when a mere infant, was deprived by death of my best friend – my mother – and the years and months which then rolled by were fraught with trouble to me. In that same position your little one is now. Allow us, then, to become friends. We could sympathize with each other.” Like any man, Genji’s actions during his life draw praise and criticism, but the fact is, Violet remains loyal and loving towards Genji as she grows older. This is an interesting insight into Japanese culture during this period, as well as to the license afforded a man of Genji’s high status.

Reading Genji now is to experience this other world that existed a thousand years ago, but no more. It will not always conform to our ways of thinking, but we shouldn’t expect that. There are subtleties in the work – its allusions to flowers, its exploration of themes, for instrance – that make it an interesting literary experience, even if many of the allusions to ancient poems and literature of the time will be lost to us. As a work of fiction, it seems remarkably modern. Despite the difficulties sometimes presented by names, Shikibu’s characters are psychologically realistic and well developed. Genji’s journey from a young impressionable boy, his career as a court lothario, and his growing maturity and weariness with the world by the end of this translation, are psychologically convincing. And the subtext, if we can call it that, of the world of women – through the women whose lives Genji touches – are varied, be they tragic or comical. But they are wholly convincing, since Shikibu’s insight into the precarious world of women is an aspect of the story that is evident to us. If you are interested in reading The Tale of Genji, you may wish to dip into this shorter version of the book first. It has its detractors, but I thought it was worth the effort.

Royall Tyler, one of the modern translators of

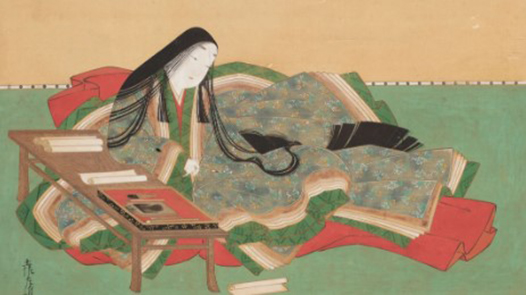

The Tale of Genji, identifies transience as a major theme. This image, taken from an online essay written by Tyler, suggests the various stages of female status. The over-the-shoulder look of the central figure seems, to me, an unwelcome acknowledgement of the possible fate of this high-status female. You can read Tyler’s essay on Genji by

clicking here.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed Facebook

Facebook Instagram

Instagram YouTube

YouTube Subscribe to our Newsletter

Subscribe to our Newsletter

No one has commented yet. Be the first!