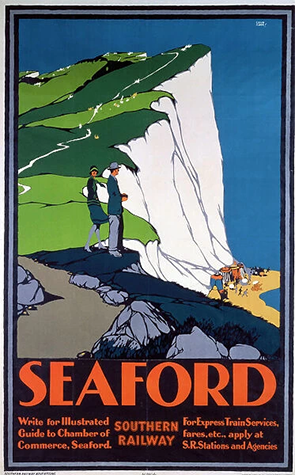

Superintendent Meredith is back with another crime to solve. After being an Inspector in the first book in this series, The Lake District Murder, Meredith is now a Superintendent and has moved to the other end of England, with a position at Lewes, East Sussex. The mystery is set on the Sussex Downs (or South Downs), an area known for its chalk downlands, with hill carvings in the chalk providing two prominent landmarks, the Long Man of Wilmington and the Litlington White Horse. While neither of these is mentioned in the story, the chalk itself plays an important part in the plot.

At first the story is just a missing person search, when a local farmer/lime manufacturer’s abandoned car is discovered in a lonely spot, with suspicious blood stains and signs of a struggle. The focus soon shifts to murder when builders find some human bones in the lime they are using on a building site. The lime turns out to have been sourced from the missing farmer’s lime business (the lime is produced by burning chalk quarried on the property in a kiln with powdered coal). An examination of other lime supplied around the district turns up more bones, almost enough to make a complete human skeleton. One major bone missing is the skull. It is thought by the police that the body of John Rother (our missing farmer) was carved up into small pieces which were gradually added to the lime kilns over a week in an attempt to dispose of the body. They assume the head was too large to be disposed of safely in the kiln. While other bones might be dismissed as animal if found, a human skull is unmistakable. Several other items were also found in the lime, such as a belt buckle, all identified as belonging to the missing Rother.

Meredith is sure that Rother was murdered by his brother William, but just as he is on the verge of making the arrest, William’s body is found, in the chalk pit. Meredith is back to square one of his investigation, now with two murders to solve.

The plot is fairly simple, and Meredith solves it, not by sudden flashes of intuition and coincidences, but by dogged routine work over several months. I had an idea of what the solution would be sometime before Meredith got there, and my suspicions turned out to be correct. That is not to say this is a boring story. Bude knows how to construct a mystery, and he is an entertaining writer. But the descriptions of the landscape, of the chalk lands and the isolated villages, are what stood out to me with this story, more than the mystery itself, which frankly, Meredith should have solved sooner. Bude doesn’t even provide a huge cast for us to be suspicious of. There are only three main characters rather than a large cast with a range of motives, which is more typical.

One of the characters is a well-known crime writer, Mr Aldous Barnet. Meredith finds him a useful source of information about the brothers and their relationship, and enjoys several long conversations with him. In one exchange between them, on the nature of detective stories, Meredith says, “But when it comes to a proper detective yarn give me something that’s possible, plausible, and not crammed with a lot of nice little coincidences and ‘flashes of intuition.’ Things don’t work that way in real life. We don’t work that way.” This initially amused me because in the other two books I’ve read in this series, Meredith does have a sudden encounter and a flash of intuition to solve the case, and I was expecting the same thing to happen this time. But it doesn’t happen this time, and Meredith solves the case only by determinedly following down every clue and scrap of information, and by being willing to start again every time a lead runs out.

This is not a flashy murder mystery. There is no glamourous setting or exotic characters, and the mystery itself is fairly simple. But it’s a well-told story with a great depiction of the place and period, and I enjoyed it.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed Facebook

Facebook Instagram

Instagram YouTube

YouTube Subscribe to our Newsletter

Subscribe to our Newsletter

No one has commented yet. Be the first!