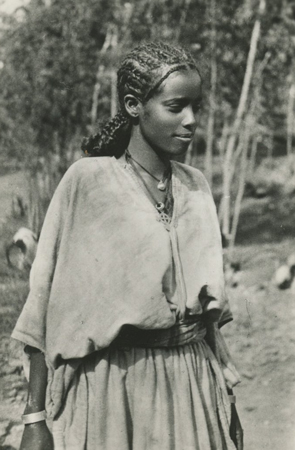

Maaza Mengiste briefly speaks of her great-grandmother, Getey, in her Author’s Note at the end of The Shadow King. In 1935, when Mussolini’s forces invaded Ethiopia, Mengiste’s great-grandmother enlisted to fight. In a case of fiction mirroring reality – Mengiste only discovered this when she was in the late stages of revising her novel before publication – Aster and Hirut, the two main female protagonists who take up arms in the struggle, were already fully formed by the time Mengiste discovered this piece of family history. Aster, the wife of an army leader, Kidane, is determined to do her part to rally and lead Ethiopian women. Hirut, orphaned and sent to live with Kidane and Aster a year-to-the-day after they suffer the loss of their only son, is made to work in the household and bunk with the family’s slave, known only as the cook. When Aster searches their quarters she finds Hirut’s gun, her Wujigra with five notches carved into it, marking the five men Hirut’s father shot. The gun, taken from Hirut for the coming war against Italy, is a source of conflict between the two women, as is Aster’s suspicions about her husband’s close relationship with Hirut: Kidane had been close to Hirut’s mother.

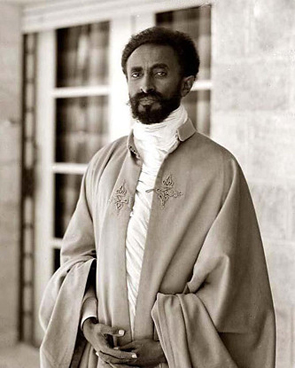

The Shadow King is based upon the war between Ethiopia and Italy beginning in 1935. Italy had failed to take the territory in the First Italo-Ethiopian War of the late 1880s. Mussolini wished to aggrandize fascist Italy with an empire, and overturning the failed attempt upon Ethiopia forty years prior was a means to this, as well as a stepping stone to other territories within Africa. The Ethiopians once again resisted, led by their emperor, Haile Selassie, until he was defeated at the Battle of Maychew and eventually went into exile in 1936. He didn’t return to Ethiopia until 1941 when Italy had once again been repelled.

Mengiste has said that her original intention for this book when she began to do research, was that it would be an historical novel of the conflict. However, as she began to discover the part played by women in the conflict, first in assisting to mobilize the Ethiopian forces, but also as soldiers, her story began to take upon a different character. Much has been made about this aspect of the novel in its promotion, and the buzz created around it when it was short-listed for the Booker Prize. And while the novel certainly gives a gripping account of this aspect of the struggle through Aster and Hirut, the book also offers well-rounded male characters: Carlo Fucelli, the Italian leader sent to suppress Kidane’s region and later ordered to build a prison from which prisoners are tossed into a gorge; Haile Salessie, the only historical figure, plagued with doubts about his own legitimacy as he waits out the war in England; and Ettore, an Italian photographer attached to Fucelli’s force, tasked with documenting the anticipated great victory, whose role later devolves into photographing the wretched prisoners whom Fucelli has thrown to their deaths.

What ties this novel together so successfully – that lifts it above a revisionist history of the role of women in war – is the ties each character has to the past and family, and their struggle with those expectations. Naturally, Aster must overcome the prejudice against women who desire to lead. When she takes her husband’s trousers and cape as a symbol of her new leadership, she comes into conflict with Kidane who threatens violence until he sees Aster’s resolve. Even then, he can imagine no other role for her other than as a support to his legitimate soldiers. For Hirut, ownership of her father’s rifle is not only a memento, but the symbol of a promise of her independence. Yet it is taken from her to furnish a male soldier.

Yet the male characters are Mengiste integral to Mengiste’s key themes. Most notably is Emperor Haile Selassie. Having fled to England with his family, his people are left rudderless and uninspired. Yet Minim, a peasant whose name means ‘nothing’ and who looks remarkably like the emperor, is able to slip into the role of emperor as a ‘shadow king’, that helps inspire the Ethiopian people to victory. Haile Selassie’s dilemma is at the heart of several characters in the story: what makes him legitimate; what is a legitimate action to take; and how does one determine a course for the future when so shaped by the past: by parents, by religion, by culture and country? Mengiste’s fictional ‘shadow king’ initially is a fictional critique of Haile Selassie’s failure to lead his people. In 1974 as Haile Salessie faces the coup that will depose him, Hirut thinks:

The real emperor of this country is on his farm tilling the tiny plot of land next to hers. He has never worn a crown and lives alone and has no enemies. He is a quiet man who once led his nation against a steel beast, and she was his most trusted soldier: the proud guard of the Shadow King.

When Haile Selassie sees reports of this imposter leading his people, he is overcome by a sense of illegitimacy:

Once, it was said that the emperor of Ethiopia was like a sun to his people. But these days have proven that we live and die in the shadows . . .

Yet Mengiste elevates her story beyond a critique of Haile Selassie’s rule. The question of how a self is formed – by the past, by parents, etcetera – is expressed through the story of the women who fight against Mussolini’s forces alongside their men, in comparison to the stories of Mengiste’s male characters. Aster, inspired by the real life Maria Uva who sang to Italian troops passing through the Suez Canal, sets aside expectations placed upon her as a woman, and rejects the tenets of her sexual role first defined by her near rape by Kidane on their wedding night. Kidane, on the other hand, is a man who has followed the furrow of history without question, whose sense of identity, unexamined, would be lost without his upbringing, his privilege and those roles imposed upon him by tradition.

It’s a thought most successfully realised in the character of Ettore, a photographer attached to Carlo Fucelli’s force. Ettore is a man clearly uncomfortable with the violence of war, yet forced to document it. As an Italian Jew, yet an atheist like his father, Leo Navarra, Ettore is the male character most likely to question his role and the violence he serves. His father has told him:

The world was built by man, my son, we are made in our own crude image, there is no fate, there is no destiny, there is no divine will, there is only this: knowledge

In a letter to Ettore, Leo tells his son, … every visible body is surrounded by light and shade. We move through this world always pulled between the two.

Leo Navarra, who exists in the novel only in Ettore’s memory and the one letter he sends to his son, elucidates a crucial point in the narrative: that legitimacy and purpose are the products of will and action, and do not reside in the destiny of kings, of nations, of religion or ideology. When Aster is forced into the wedding chamber for the first time the cook tells her, There is no escape but what you make from inside

Faced with rape, herself, a voice in the novel’s chorus (yes, just like in Greek theatre) tells Hirut There is no escape but what you make on your own.

When Ettore faces his own precarious status as a Jew, he remembers the words of his father, long ago: There is no way but forward, my son. That is the only true escape.

It is forward into the future, not the past, that characters must go. It is through their own agency, not God, nation or king, that they will become who they will become. Light and shade is the binary coupling through which the novel defines these states. Minim is a shadow king because he imitates the emperor, but he is a legitimate inspiration to the emperor’s people, and the real emperor in the eyes of Hiruit. Haile Salessie, on the other hand, fails to lead and therefore exists in the shadows of history. Ettore is a photographer, working with shadow and light, with an uneasy relationship with his prisoner subjects that mirrors his own moral journey. And the women of this story represent a conscious choice to take their place in history. Against the traditional expectations of women, expressed in the Empress Menan’s radio announcement (that it was women’s role to speak against war) Hirut and Aster choose instead their own path.

There is no past, there is no “what happened”, there is only the moment that unfolds into the next, dragging everything with it, constantly renewing. Everything is happening at once.

Mengiste’s novel is highly readable and entertaining. I found it to be page-turning from the start. Yet it is also a philosophical exploration of the self and one’s place in history. All characters are either constrained or resist the roles of social expectation, historical imperative and what might otherwise be called destiny. There is a heroic sense that accompanies these struggles and that justifies the Homeric allusions in its imagery and Choric voices, used as commentary within the story. It’s a story that is multi-faceted and refuses to take sides. I loved it not only as a previously untold story about the role of women in war, but as a story that attempts to explore the humanity of its characters in relation to their historical moment.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed Facebook

Facebook Instagram

Instagram YouTube

YouTube Subscribe to our Newsletter

Subscribe to our Newsletter

No one has commented yet. Be the first!