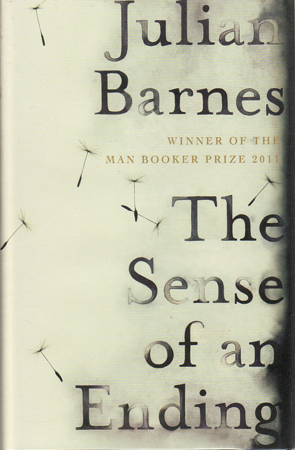

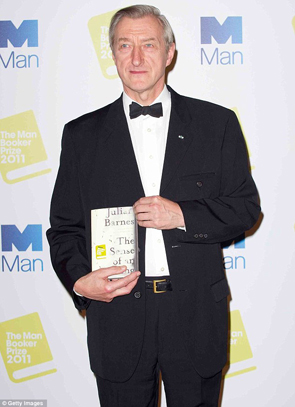

I’ve reread Julian Barnes’s The Sense of An Ending as part of our Special Reading Project to attempt to review all the Man Booker Prize winners. I first read it when it came out and remember enjoying it, although I had really forgotten what it is about. In my last year of teaching I came across it again as an extract from the beginning of the novel used in an exam as part of a reading assessment. The extract was about those impressionistic memories we have of our school days from later life. I was struck by how unfamiliar the extract seemed; how quickly I could forget a book I spent time reading and enjoyed.

Which is what the book is predominantly about; the past and memory. Told from the perspective of Tony Webster in his retirement years, the first part of this book gives an overview of Webster’s life, from his early years at school with his friends Colin, Alex and the new boy Adrian Finn. Adrian is different to the other boys. His intellect surpasses that of their teacher, Old Joe Hunt, and he becomes central to the group’s intellectual development. Webster traces his life from these early memories up to his present older self, now retired and divorced. Webster’s account of his life is patchy and impressionistic, always qualified with the sense of memory’s unreliability. He is aware that his recount of his school years is now little more than a series of anecdotes, and his memories of his early relationship with Veronica is coloured by his inexperience and his sexual frustration at her withholding. Added to this is his shifting perspective as he looks back with an increasing understanding of how things turned out. Of greatest import is his eventual breaking up with Veronica after he is made to feel unworthy at a family weekend, and then Veronica’s later relationship with Adrian. These circumstances and time splits the friendship of the school group apart. Adrian and Veronica’s relationship eventually suffers a terrible end with Adrian’s death, and in the last pages of the opening section of the book, Webster’s narrative is compressed – a seemingly sudden marriage to Margaret and equally sudden appearance of a daughter, Susie, is told succinctly – suggesting both the psychological partiality of perceived time as well as the sense of the mundanity of life, of years slipping away into middle class urbanity, along with his dreams and aspirations, as though the formative years of youth bear a disproportionate weight in defining us. All this may have been the subject of a well-told, if unremarkable novella: the documentation of a life. But with the death of Veronica’s mother and an unusual bequest, Tony is forced to re-evaluate his life and his understanding of his past.

Apart from establishing the key relationships in the novel, the recount of Webster’s school years also establishes the thematic concerns of the novel. If Webster and his friends seem somewhat too precocious in their discussion of philosophy, literature and history, we are also aware, as Webster points out, that this is a representation of his formative years, coloured by insights and given significance from a lifetime of reflection upon a life that developed from this period. When Old Joe Hunt asks Marshall, a typical schoolboy who has enjoyed his holidays, what he has learned about the period of Henry VIII, Marshall replies There was unrest, sir.

When pressed for more information, he elaborates, I’d say there was great unrest, sir.

The scene is hilarious, but it also underlines the problems of memory and historical record. Adrian, a far deeper thinker, approaches the problem of history, and by extension, as we see in Webster’s recount as it unfolds, of personal memory. When pressed on the matter of the origins of the First World War, Finn argues:

. . .isn’t the whole business of ascribing responsibility a cop-out? We want to blame an individual so that everyone else is exculpated. Or we blame a historical process as a way of exonerating individuals. Or it’s all anarchic chaos, with the same consequence. It seems to me that there is – was – a chain of individual responsibilities, all of which were necessary, but not so long a chain that everybody can simply blame everybody else . . . That’s one of the central problems of history, isn’t it, sir? The question of subjective versus objective interpretation, the fact that we need to know the history of the historian in order to understand the version that is being put in front of us.

It’s a brilliant setup for the second half of the novel where the real story occurs. When Webster tries to argue with Old Joe Hunt that Robson’s actions, a schoolboy who has committed suicide, were little understood – therefore, what hope is there in understanding the distant past – Old Joe’s response brushes away the old chestnut that history is written by the victors, thereby discrediting the binary approach Adrian Finn has already eschewed, to consider the range of evidence that may bring insight to a life. Already Webster is missing the point of class discussion, and it will take a lifetime to learn the lesson that Adrian understood instinctively; to understand Adrian, in fact, Veronica, and his own self.

This is a remarkably dense book – dense in terms of the period of time it covers and the multitudes of detail, and remarkable for its brevity – but one that is highly readable and thought provoking. It’s going to be enjoyed more, I suspect, by someone in their middle age who has the experience to understand Webster’s constant attempts to understand the past, his own actions and motivations and the circumstances in which he finds himself. There is a sense in the way this book is written and structured that living is what we do, perhaps not so successfully when we’re young, and understanding it all is what we attempt when we’re older.

While this review may seem to give much of the plot away, I have really only discussed Barnes’s opening, which is only the set-up for the main bulk of the story. In fact, there is a certain level of unpredictability about the second two thirds of the book. While the latter story centres around Webster’s attempt to understand his bequest, it reads something like a detective fiction, too, with a denouement worthy of a detective plot, and with all the poignancy this novel deserves. This was a worthy winner of the Man Booker, in my opinion. It can easily be read in one long sitting, and I think it’s a book that benefits from a repeat reading.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed Facebook

Facebook Instagram

Instagram YouTube

YouTube Subscribe to our Newsletter

Subscribe to our Newsletter

No one has commented yet. Be the first!