The School Run isn’t about the daily grind of getting the kids fed and to school. It is a satire: the kind of story that makes you wonder how we have gotten to where we are. The ‘run’ here is the competition to get into a school. It’s about the competitive world of selective high schools, of status and perceived success. It’s about the lengths to which some parents will go to ensure their child succeeds. As a former teacher, so much of this book rang true to me. It may be an exaggeration, but not by much.

The story focusses on three families who are trying to get their children through the selection process for St Ignatius’ Boys school in the coastal town of Pacific Pines. Estella and Bec are two neighbouring school mums. Both have year six boys. Estella has twin boys, in fact. Each mother has made it their goal to get their boys into the private school, with no thought that Pacific Pines High, the local comprehensive school, should even be considered.

On the surface, Estella and Bec couldn’t be more different. Bec is friendly, and is a caring mother who dotes on her children: Willow, almost eighteen years old, Cooper, about to head to high school and Sage, almost ready for kindergarten.

Estella, however, appears brash. She is sometimes downright nasty and as a parent her relationship with her daughter, Felicity, who is almost eighteen, appears very strained and uncaring. However, with her twins, Archie and Jonty, she is firm but fair. Both Estella and Bec have husbands supporting their families. They are also close friends who appear to support one another.

A new mum, Kaya, arrives next door to Estelle, with her son Ollie, also about to head to high school. She is carefully scrutinised by Estelle, especially with regard to her marital situation. In fact, Estelle is very rude to Kaya, a recently widowed mum. Kaya forms a bond with Bec instead, because of the way Estelle treats her.

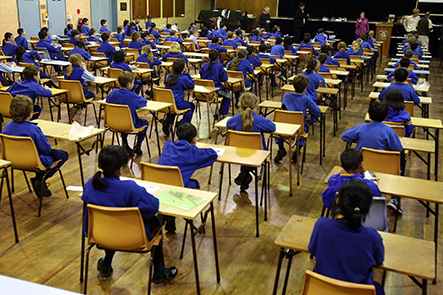

All three mothers are insistent that their boys will attend the prestigious St Ignatius and through one means or another, they are prepared to do anything to make this a reality. Students are put through a series of physical tests and a rigorous interview process when applying for the school, while parents each have different tactics for their children to succeed. The competition between parents starts there. But as time goes on the women find that they may not only need to protect their own, but also form alliances to repress secrets that may be revealed – lies and scandals – which could have long term impacts upon them getting their school of choice. As time goes on, these alliances shift as people learn more about others and indeed, themselves.

Ali Lowe seems to target the worst aspects of parent behaviour and the system that produces it. Natural parental concern is twisted by competition, until a child’s education and growth become secondary to concerns about status, rank, and how their child can be number one. Competition is healthy to a degree, but the pressures of economic and social status mean some parents are willing to do anything, including paying expensive tutors for long hours outside school, and even to engaging in anti-educational practices like plagiarism: writing for their children or paying tutors to write papers in order to be accepted into selective schools and achieve the best results while there. That’s the kind of culture The School Run derides. As a former teacher, I know these are issues increasingly faced by educational institutions. In Australia there has been a long trend toward devaluing public comprehensive education, so it often does not occur to some parents that their child can likely achieve as good a result and have a more rounded schooling in the comprehensive local school. Unfortunately, the effects of private and selective high schools, at least in New South Wales – of attracting the most capable students – means that leaving results often reinforce the perceptions about quality.

St Ignatius puts their prospective students through a gruelling gala day of sports followed by interviews. It is meant to be gruelling, to weed out those not up to the level required. In The School Run, they even compare the experience to The Hunger Games: prior to the ‘games’ the boys are told, ‘May the odds be forever in your favour’. I can’t imagine why you would want to put yourself or your child through that. However, these parents, with delusions that private is best, will stop at nothing. One mother uses her baking skills to gain kudos with the Principal and school board, one works for free in the church and feigns Catholicism, and the other slanders other parents and children while working to improve their own child’s chances, by cheating on the actual gala day.

Our own school system produces similar parents. Each year students sit a range of tests for entry to selective high schools. Having done everything possible prior to prepare for the tests, a recent group of parents could not even wait to find out whether their children had been accepted, so they hacked into the system to find out early. What they thought they could do at that point to warrant such a move is beyond me, but that is the kind of desperation that the system and the culture it produces encourages. There are moral risks involved in this kind of example, as well as entrenching perceptions of class – of entitlement – and a belief that it is acceptable to use any means to get ahead.

The School Run talks of Perfect students, Perfect parents, the Perfect crime. While there are none of these in reality, in this case there is a perfect crime. I don’t wish to spoil the plot so I won’t go into this, but read the book to find out how far someone might go. It’s well worth it.

I thoroughly enjoyed this book and recommend it. It has an interesting range of characters, all of whom I have met as other people in my teaching career, some in similar situations, although not, to my knowledge anyway, to these extremes. This is Ali Lowe’s third book, so I will certainly seek out her other two. This one is well written with believable characters and a story line I found to be easily relatable. Perhaps for teachers, as it did with me, it may strike even more of a chord.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed Facebook

Facebook Instagram

Instagram YouTube

YouTube Subscribe to our Newsletter

Subscribe to our Newsletter

No one has commented yet. Be the first!