I was young and sheltered. I’d just started university and I was shocked by the amount of graffiti in the cubicles of university toilets. Some comments spawned ongoing conversations, like a modern thread on social media, with the same kind of vituperative responses, back and forth. But one piece caught my eye, written in darker pen, and it has remained with me, not as a tenet of my thinking, but as a seminal insight into political ideals. It read, “If you’re not a Socialist before you’re 18 you haven’t got a heart. If you are a Socialist after you’re 18 you haven’t got a brain.” I recalled this as I read George Orwell’s The Road to Wigan Pier. “One can observe,” Orwell writes, “on every side that dreary phenomenon, the middle-class person who is an ardent Socialist at twenty-five and a sniffish Conservative at thirty-five.” If there is one takeaway from this book, it is that in 1930s England Orwell thought it important to promote the Socialist cause to stave off the threat of Fascism and to address poverty. But Orwell is writing against common prejudices (not the least of which he shares) about class and wealth. There is a vast difference in the interests of the lower-middle class and their richer brethren he argues. Some in the middle-class, while they may be educationally and psychologically different to their working-class counterparts, are potentially as economically vulnerable. The first part of this book aims to document the terrible conditions many working-class people face in coal mining towns, as well as the unemployed. Orwell faces common prejudices against the working class – that they’re lazy, or they smell – and suggests that they too possess a level of dignity and humanity that is often overwhelmed by their economic plight. Orwell wants us to feel for the working-class. In the second half of the book he is essentially focussed on the middle-class and the problems of engaging them in a social struggle they may not understand is theirs, too.

The Road to Wigan Pier was published in 1937 and begins as an account of the living and working conditions of the poor in coal mining towns like Wigan, Sheffield and Barnsley. The writing here is informed by Orwell’s own experience of living in these towns while he conducted research for this book. Its documentary style benefits from the detail and empathy you would expect from a skilled novelist. The second half of the book addresses the problems raised in the first – of the poverty, unemployment and hunger faced by the poor – but also addresses the wider political context of the 1930s. Fascism was on the rise in Europe and Orwell believed that the only way to stem its rise in England was by introducing Socialist ideals into the political system. He describes the challenges faced to change the attitudes of ordinary people against Socialism and how better advocacy was needed to appeal to these people.

Orwell began this book at the request of Victor Gollancz almost immediately after he submitted the manuscript for his novel, Keep the Aspidistra Flying. Victor Gollancz was a left-wing publisher who ran the highly successful Left Book Club, a publication he began in 1936. The Road to Wigan Pier was commissioned as part of Gollancz’s efforts to promote social reform. The large subscription audience of the Left Book Club – only members received its publications – would make The Road to Wigan Pier Orwell’s best-selling book. Nevertheless, the publication of the book was fraught since Gollancz felt compelled to write a forward that criticised some of what Orwell had to say. Gollancz wanted Orwell to remove the second part of the book which discusses the wider issues around Socialism and Fascism and expand the first half which describes the plight of the working poor (as well as the unemployed) in more detail. Gollancz objected to Orwell’s characterisation of Socialists, not only as ‘cranks’, but Orwell’s implicit criticism of progressive movements like vegetarianism and feminism, as well as his decision to play devil’s advocate in addressing the problems faced by Socialism to win converts in England. Orwell refused to do this and Gollancz decided to publish the book with the forward he wrote himself, inserted to address the issues he had with the second part of the book. Gollancz’s forward is still included in many editions, but not all. It wasn’t in my edition. If you wish to read the forward, click here. It’s about three and a half thousand words, so I’ve placed it on another page which will open in a new tab.

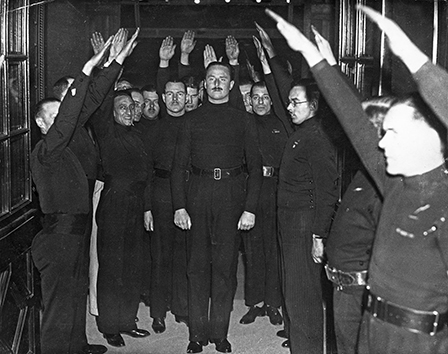

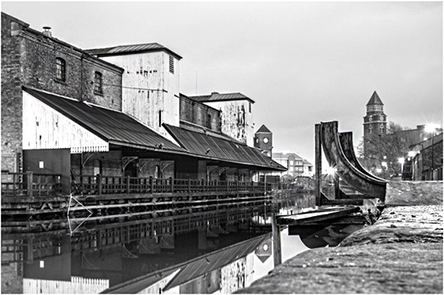

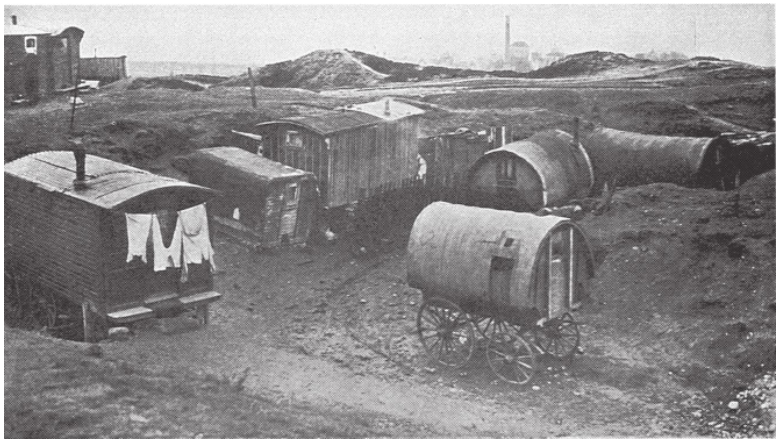

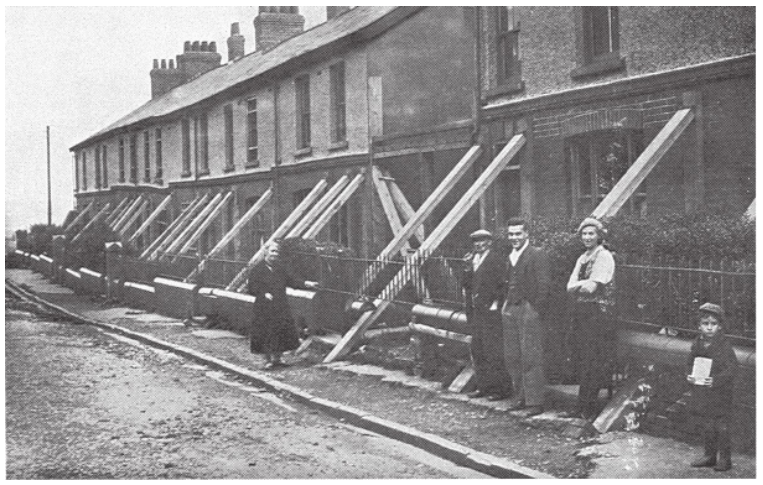

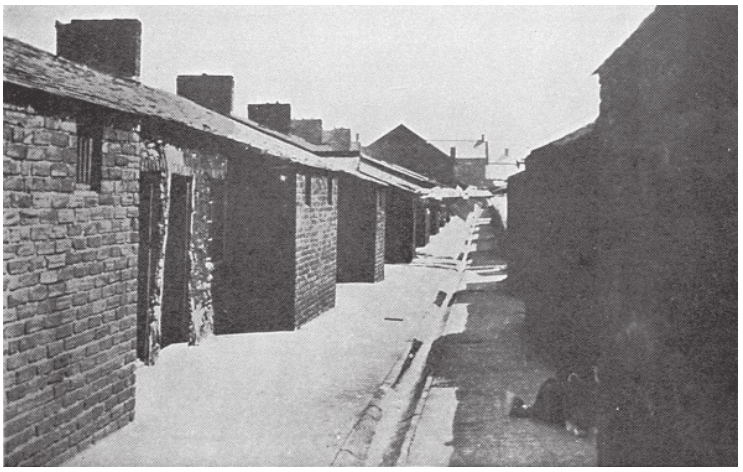

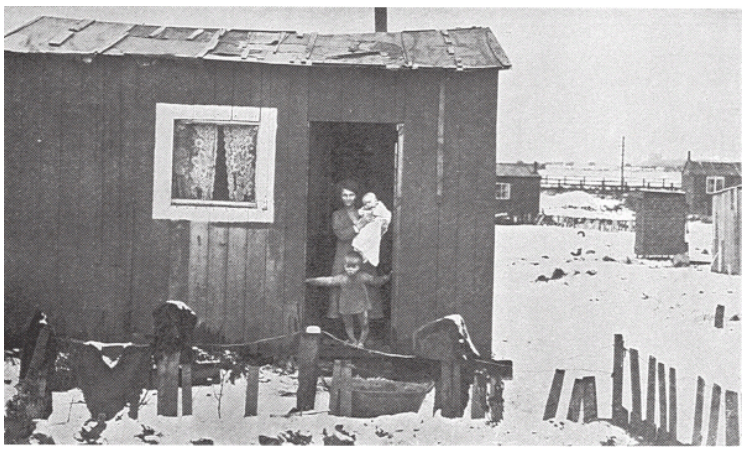

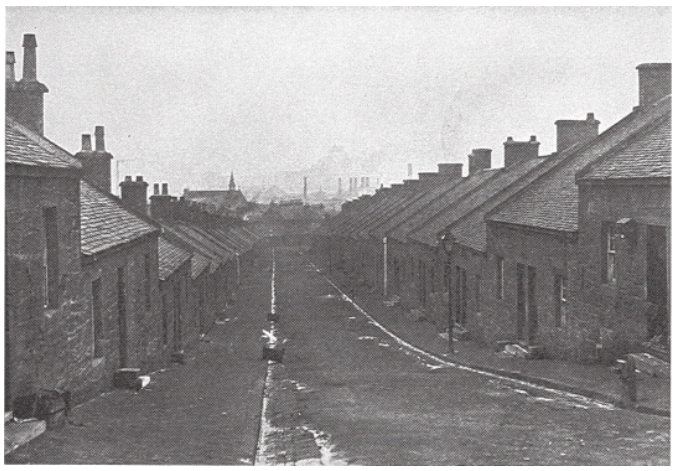

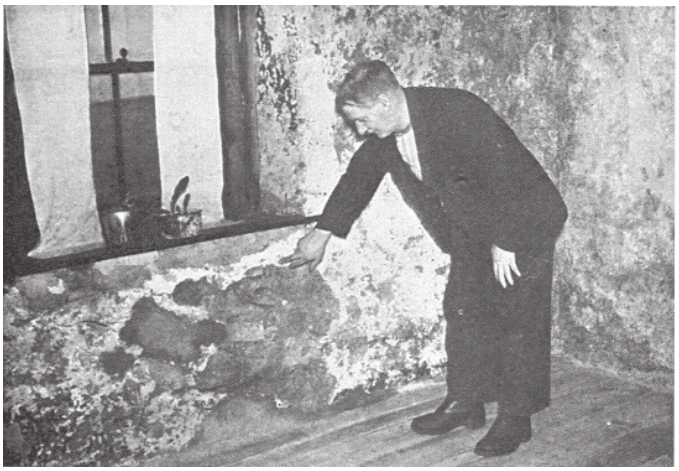

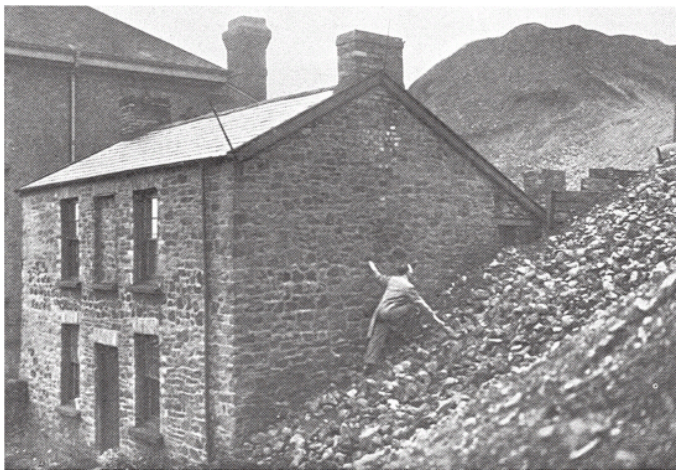

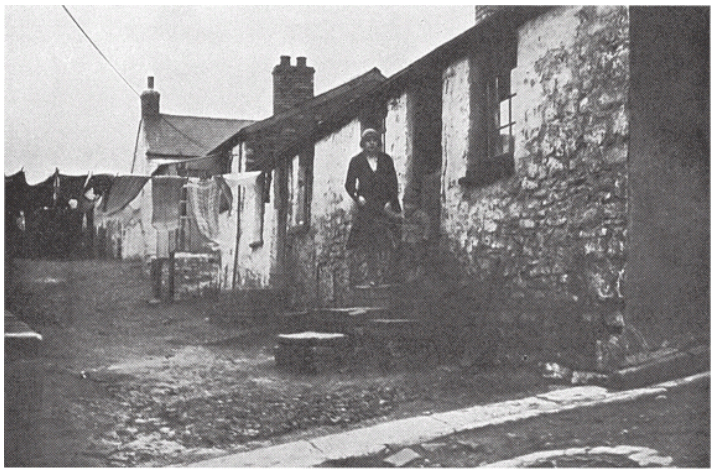

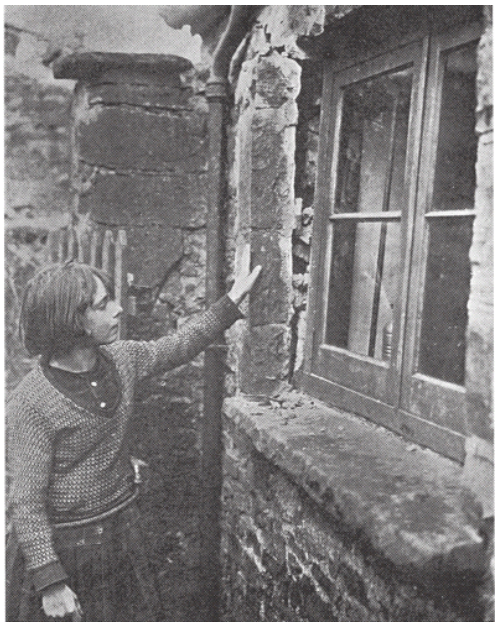

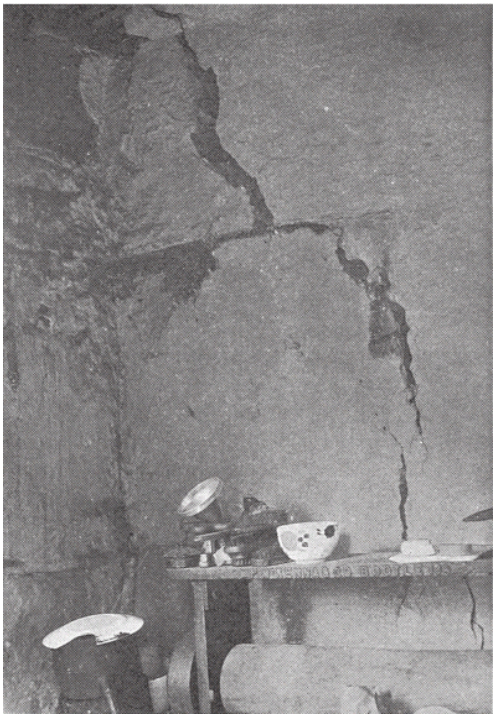

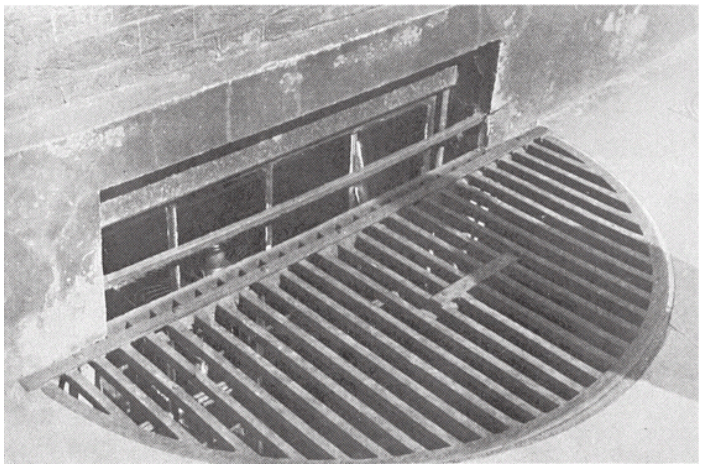

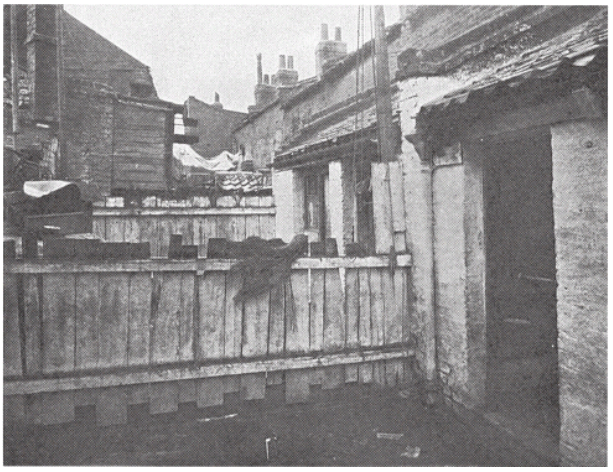

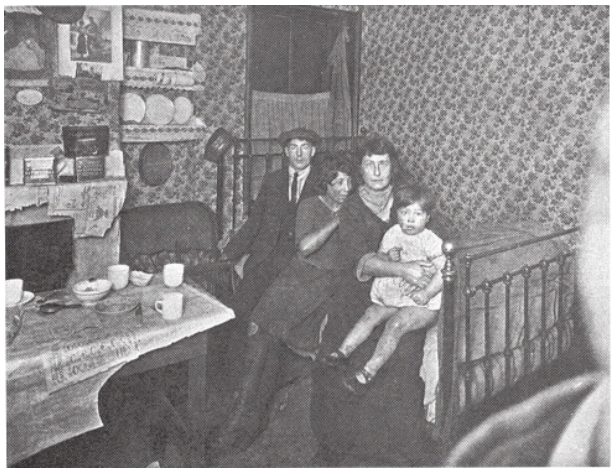

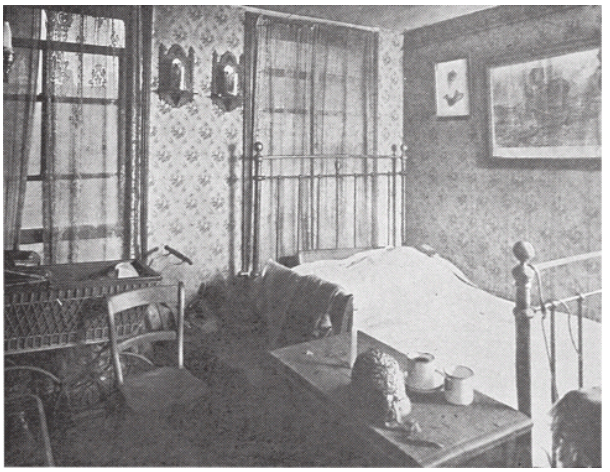

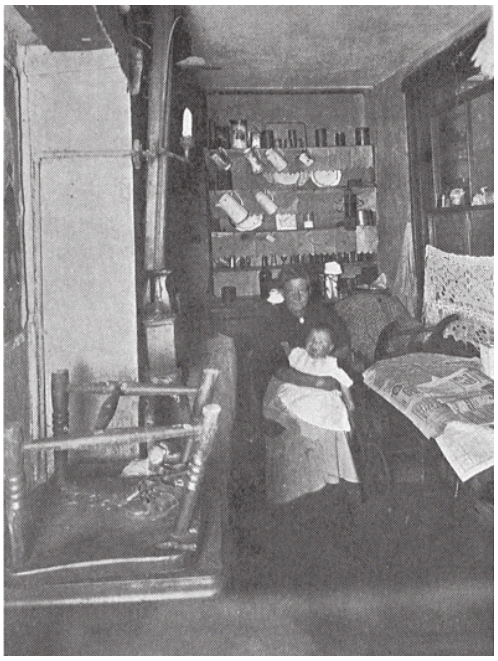

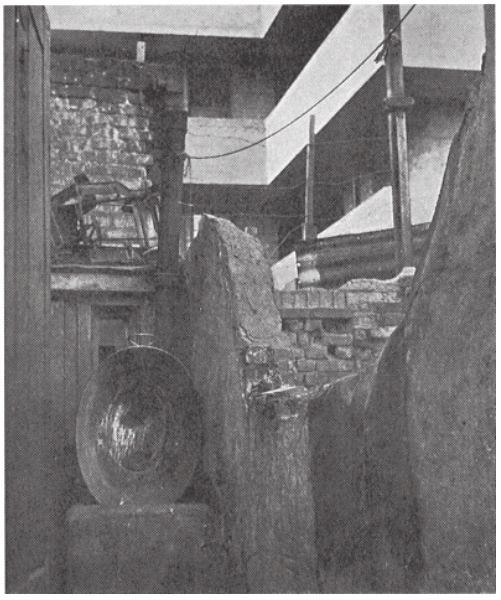

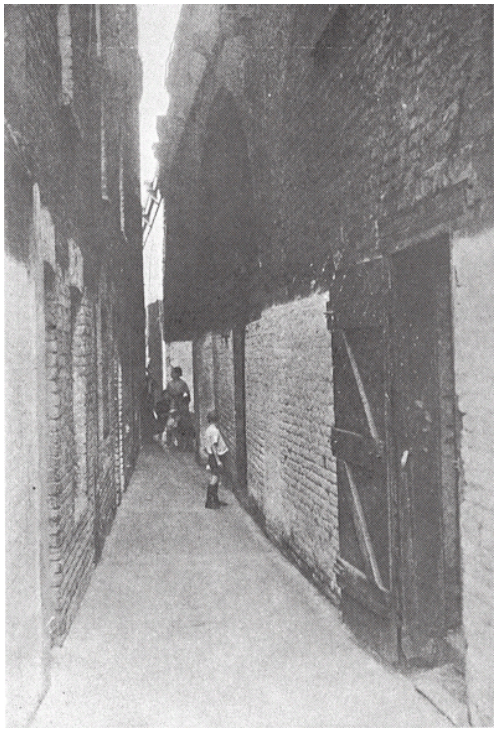

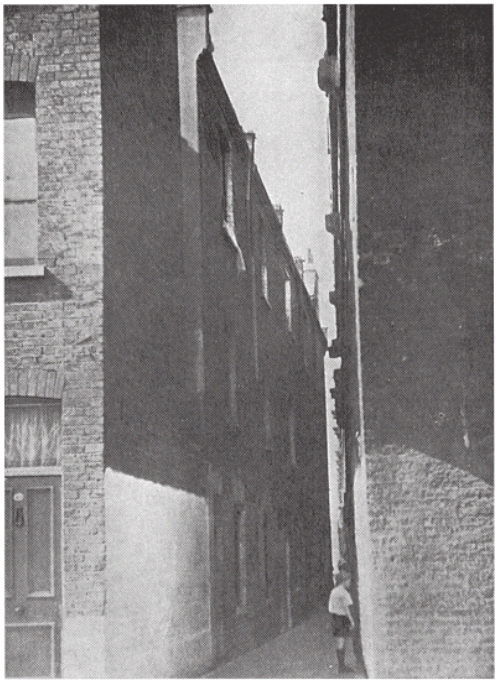

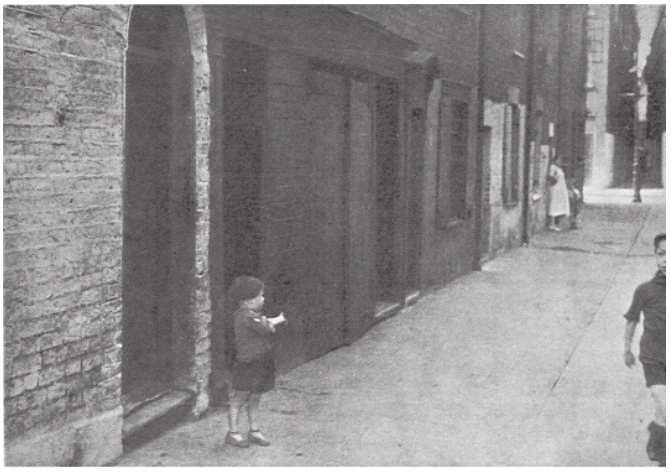

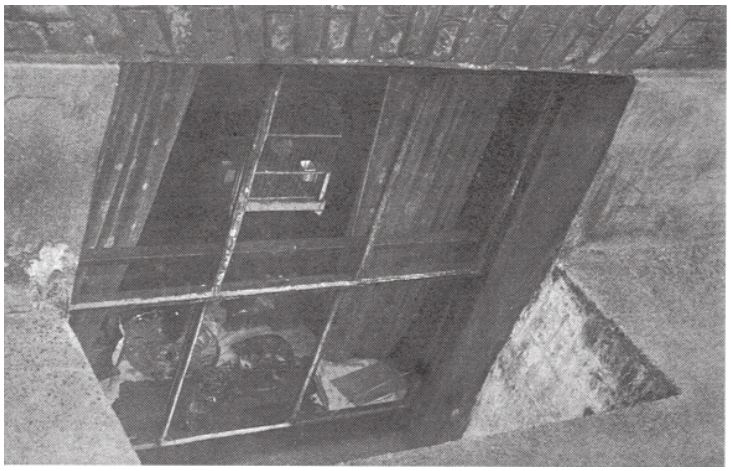

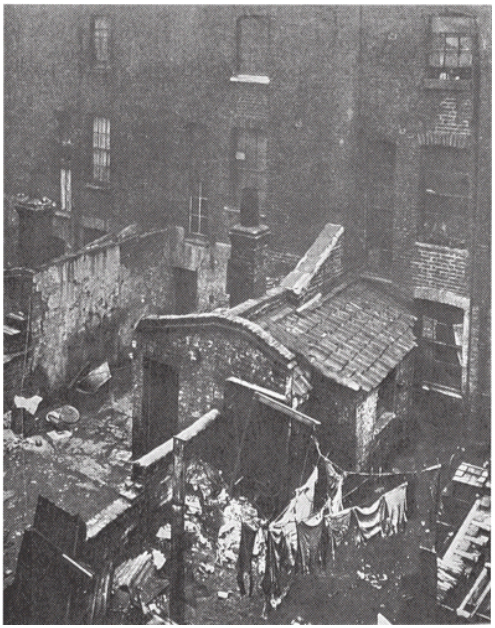

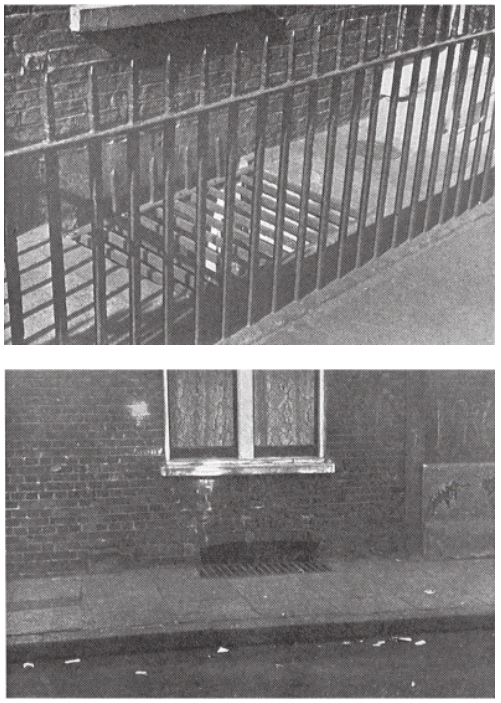

The first edition also included thirty-two photographic plates that showed the living conditions of the poor in the areas of England that Orwell writes about. Later editions didn’t include the photos, but Harcourt, Brace included them in their 1958 edition, and the 1986 Complete Works edition did, also. Other later editions may include them, but at the time of writing the images are difficult to find on line, so for those interested I have included all thirty-two photos in a carousel below, accompanied by their original captions. It is not clear whether Orwell wanted the photographs included or if he had anything to do with their inclusion, but they are a nice illustration of his subject matter, nevertheless.

The objections made by Gollancz to Orwell’s characterisation of Socialist ‘types’ might also be taken up by modern readers – in fact they will now be read in an entirely different context to which they were first written – so I will quote two sections here to discuss:

One sometimes gets the impression that the mere words ‘Socialism’ and ‘Communism’ draw towards them with magnetic force every fruit-juice drinker, nudist, sandal-wearer, sex-maniac, Quaker, ‘Nature Cure’ quack, pacifist and feminist in England. [161]

. . .

I have here a prospectus from another summer school which states its terms per week and then asks me to say ‘whether my diet is ordinary or vegetarian’. They take it for granted, you see, that it is necessary to ask this question. This kind of thing is by itself sufficient to alienate plenty of decent people. And their instinct is perfectly sound, for the food-crank is by definition a person willing to cut himself off from human society in hopes of adding five years onto the life of his carcase; that is, a person out of touch with common humanity. [162]

. . .

We have reached a stage when the very word 'Socialism' calls up, on the one hand, a picture of aeroplanes, tractors and huge glittering factories of glass and concrete; on the other, a picture of vegetarians with wilting beards, of Bolshevik commissars (half gangster, half gramophone), of earnest ladies in sandals, shock-headed Marxists chewing polysyllables, escaped Quakers, birth-control fanatics and Labour Party backstairs-crawlers. Socialism, at least in this island, does not smell any longer of revolution and the overthrow of tyrants; it smells of crankishness, machine-worship and the stupid cult of Russia. [201]

Gollancz’s response to these opinions should be more relatable for modern readers:

There is an extraordinary passage in which Mr. Orwell seems to suggest that almost every Socialist is a “crank”; and it is illuminating to discover from this passage just what Mr. Orwell means by the word. It appears to mean anyone holding opinions not held by the majority— for instance, any feminist, pacifist, vegetarian or advocate of birth control. This last is really startling. In the first part of the book Mr. Orwell paints a most vivid picture of wretched rooms swarming with children, and clearly becoming more and more unfit for human habitation the larger the family grows: but he apparently considers anyone who wishes to enlighten people as to how they can have a normal sexual life without increasing this misery as a crank! The fact, of course, is that there is no more “commonsensical” work than that which is being done at the present time by the birth control clinics up and down the country — and common sense, as I understand it, is the antithesis of crankiness.

I am willing to concede that Orwell lived in an era of different social attitudes, with prejudices that were more acceptable to the mainstream, but Gollancz’s criticism of Orwell is reasonable given the problems he is identifying regarding the cost of living and undernourishment among the poor. And Gollancz’s defence of pacifism and feminism, among other things, makes his position more acceptable to modern thinking, too.

However, while we will make Orwell own what he is said – we may even call him a “crank” if we wish to take him to the woodshed of our minds – the fact remains that Orwell is making a point in these prejudicial screeds. His assertion that Socialism has a poor public image is based on a belief that many ordinary people who might otherwise accept its tenets are alienated by people whom they consider too radical or with whom they cannot relate. The question remains whether that was the case, but Orwell’s argument is essentially similar to Gollancz’s: that Fascism was gaining ground in Europe and England: that if Capitalism had failed to manage industry to benefit the working class, then Socialist ideas would need to reverse that trend:

ORWELL: “To oppose Socialism now, when twenty million Englishmen are underfed and Fascism has conquered half Europe, is suicidal. It is like starting a civil war when the Goths are crossing the frontier.”

GOLLANCZ: “. . . the machine of capitalist industrialism . . . is visibly breaking down: that such break-down means poverty, unemployment and war: and that the only solution is the supersession of anarchic capitalist industrialism by planned Socialist industrialism.”

Orwell offers a brilliant insight into the conditions of the working classes in England during the 1930s, as well as the perceived threat from Fascism. By 1937 when The Road to Wigan Pier was published there was a general sense that another war was likely in Europe. Both Germany and Italy had Fascist governments. Fascist movements were also growing in America and England. Sir Oswald Mosley, a member of parliament, formed the British Union of Fascists in 1932 (known as the ‘British Union’ in 1937) and the government felt threatened enough by the party that in 1936 it moved to ban political uniforms and military-style organisations. However, Orwell saw the allure of Fascism more threatening than any single politician:

When I speak of Fascism in England, I am not necessarily thinking of Mosley and his pimpled followers. English Fascism, when it arrives, is likely to be of a sedate and subtle kind (presumably, at any rate at first, it won't be called Fascism), and it is doubtful whether a Gilbert and Sullivan heavy dragoon of Mosley's stamp would ever be much more than a joke to the majority of English people; though even Mosley will bear watching, for experience shows (vide the careers of Hitler, Napoleon III) that to a political climber it is sometimes an advantage not to be taken too seriously at the beginning of his career.

Orwell, in responding to the rise of Fascism, acknowledges that either Communism or Capitalism can devolve into Fascism, but in 1937 the perception was that the failure of capitalism to address the needs of the poor increased the need for a Socialist response.

Orwell’s approach to this subject matter is highly engaging, at least in the first part of the book, and even in the second part if you are not averse to political writing. The beginning of The Road to Wigan Pier feels like reading a novel. We are introduced to characters in the lodgings of Mr and Mrs Brooker: Mr Reilly the mechanic, unemployed Joe, Old Jack etc. The first chapter is highly personal as it describes Orwell’s reactions to the poor living conditions in the house: the cramped space, the filth, the terrible food and a full chamber pot that is found under the breakfast table. And when Orwell leaves the residence, disgusted, we understand that he intends to criticise the Brookers, not their boarders, since their poverty condemns them to this life. We sense this intention in a the moment he captures, observing the hopelessness of a young woman he sees from a train, trying to clear a drain pipe:

It struck me then that we are mistaken when we say that ‘It isn't the same for them as it would be for us’, and that people bred in the slums can imagine nothing but the slums. For what I saw in her face was not the ignorant suffering of an animal. She knew well enough what was happening to her—understood as well as I did how dreadful a destiny it was to be kneeling there in the bitter cold, on the slimy stones of a slum backyard, poking a stick up a foul drain-pipe.

Likewise, Orwell’s description of conditions in coal mines gives a real sense of how hard life was. Miners working in older shafts were sometimes required to walk bent over for several miles underground before they reached the coal face – ‘travel’ time for which they were not paid – before they started hours of filthy, hot, backbreaking work. Orwell, himself, entered one of these shafts and describes the debilitating effects of the experience on himself.

Orwell’s documentary eye also falls upon attitudes against the unemployed and the economic realities that make them so, as well as the real impoverishment of the families on social security and the psychological torment felt by men who are likely unable to ever find work again.

The first half of the book is a highly engaging human story. However – and this will depend upon individual readers – some sections of the book will be of less interest than others. The second part which Gollancz objected to meticulously teases out the differences between classes, as well as the difference between class and economic status, and is broadly focussed upon the specific social and political problems of 1930s England. Despite Orwell’s discussion of his own upbringing and his growing awareness of his middle-class social status and the importance of race in his experiences in Burma, it is less a human story than the first part of the book.

Nevertheless, I think Orwell’s arguments in this section have applicability to the lives of modern readers, still. Orwell is speaking about Capitalism and Industrialism, and the effect on the working lives of the working-class. But changes to society in our modern era as a result of technological innovation are still with us. Orwell understands the potential of machines to encroach upon working lives; how they might threaten a sense of purpose:

There is scarcely anything, from catching a whale to carving a cherry stone, that could not conceivably be done by machinery. The machine would even encroach upon the activities we now class as 'art'; it is doing so already, via the camera and the radio. Mechanise the world as fully as it might be mechanised, and whichever way you turn there will be some machine cutting you off from the chance of working—that is, of living.

He goes further to say:

There is really no reason why a human being should do more than eat, drink, sleep, breathe and procreate; everything else could be done for him by machinery. Therefore the logical end of mechanical progress is to reduce the human being to something resembling a brain in a bottle.

It strikes me that this must have been received as a little overly-dramatic in the 1930s, but it seemed to me as I read that the application of this thinking to the threats posed by Artificial Intelligence now makes it less so for modern readers. In the last few months the problem of AI being used by students in universities and schools to write essays has become prevalent, as well as the difficulty, now, of detecting it. It is not inconceivable that at some stage in the future, if you were to read a review like this, you might simply assume it was written by a computer. While Orwell was concerned about the potential of machines to deskill workers, the potential of machines to make critical thinking somewhat redundant, now, seems not so exaggerated.

And the political landscape of our modern world has some similarities. Orwell makes an argument that the poor middle-class can be persuaded to act politically against their own best interests:

When the pinch came nearly all of them would side with their oppressors and against those who ought to be their allies. It is quite easy to imagine a middle class crushed down to the worst depths of poverty and still remaining bitterly anti-working class in sentiment; this being, of course, a ready-made Fascist Party.

The argument recalls to my mind instances in Australia when working-class communities have found appeal in conservative politics, as well as the support the American GOP has enjoyed from working-class Americans when its agenda has traditionally focused upon capitalist interests.

I think The Road to Wigan Pier still has a lot to offer modern readers, whether it be for its human story, its historical interest, or the insights it might even offer into our own lives. As modern readers we are given an insight into the living and working conditions of the poor in 1930s England. Orwell treats us to an analysis of the social and political landscape of the time, not to mention his own prejudices (and presumably those of a majority). But we have to understand, also, that Orwell criticises Socialism and its advocacy, not to tear it down, but to find a way to raise it. To do this he has to break through traditional notions of class difference and frame the argument as an economic problem, just as he separates issues of character and economy when he speaks about the working-class. Victor Gollancz surely understood this – he acknowledges that Orwell is playing devil’s advocate – but maybe he didn’t trust his readers to understand this as much as Orwell did. That dynamic between these two men is yet another interesting aspect of this book.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed Facebook

Facebook Instagram

Instagram YouTube

YouTube Subscribe to our Newsletter

Subscribe to our Newsletter

No one has commented yet. Be the first!