“But the thumb-mark, my dear fellow!” I exclaimed. “How can you possibly get over that?”

“I don’t know that I can,” answered Thorndyke calmly; “but I see you are taking the same view as the police, who persist in regarding a finger-print as a kind of magical touchstone, a final proof, beyond which inquiry need not go. Now, this is an entire mistake. A finger-print is merely a fact—a very important and significant one, I admit—but still a fact, which, like any other fact, requires to be weighed and measured with reference to its evidential value.”

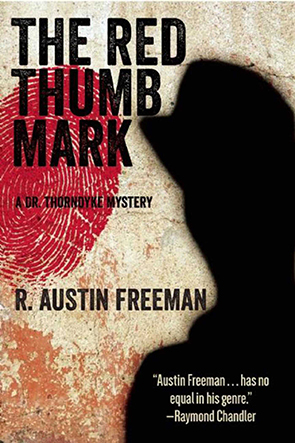

R Austin Freeman’s Dr Thorndyke mysteries don’t seem to be highly regarded these days, and certainly Freeman’s writing style isn’t as exciting as many of the other Golden Age writers. The Red Thumb Mark is actually Edwardian, and it would probably be more appropriate to compare Freeman to Arthur Conan Doyle rather than Agatha Christie or Dorothy L Sayers (Doyle published the Holmes stories between 1887 and 1927, spanning the Victorian and Edwardian eras). But Freeman was one of the founding members of the Detection Club, and he continued to write mysteries until his death in 1943, so he gets included with other Golden Age writers.

Thorndyke is similar to Sherlock Holmes in many ways, with his keen reasoning and attention to detail. Freeman actually finds fault with Holmes’s deductive methods in this book. On page 75 he makes observations about a man he sees in the distance and concludes that the man is a stationmaster. He explains all the observations that led him to this deduction, but then continues with the following qualification:

. . . he agrees with a general description of a stationmaster. But if we therefore conclude that he is a stationmaster, we fall into the time-honoured fallacy of the undistributed middle term – the fallacy that haunts all brilliant guessers, including the detective, not only of romance, but too often also of real life. All that the observed facts justify us in inferring is that this man is engaged in some mode of life that necessitates a good deal of standing; the rest is mere guess-work.

Holmes would never admit to such a statement. Like Doyle, Freeman was a medical doctor, and this undoubtedly helped him in his creating the character of Dr Thorndyke. Freeman’s books are known for their scientific accuracy and method. Thorndyke is both a doctor and a lawyer, specialising in the medical/scientific aspects of legal cases. In some ways he is an early model of Dr Kay Scarpetta (Patricia Cornwell’s Chief Medical Examiner in her Scarpetta novels, written between 1990 and the current day, with probably more to come). Freeman actually carried out the experiments described in his books to ensure that they worked and produced the results he described.

The Red Thumb Mark is narrated by Dr Jervis, an old friend of Thorndyke’s. They meet randomly in the opening pages of the book, and are together when Thorndyke is called to consult in a new case, that of Reuben Hornby. Jervis takes on the Watson role in the story, as loyal sidekick and narrator. Reuben is accused of stealing diamonds from his uncle’s safe. The only evidence against him is a thumbprint made in blood left on a piece of paper in the safe. The thumbprint is a perfect match for Reuben’s left thumb. He is arrested and a trial date is set. Most of the book involves Jervis describing his and Thorndyke’s actions leading up to the trial. The second and third last chapters cover the trial, and the final chapter wraps up a personal side story for Jervis.

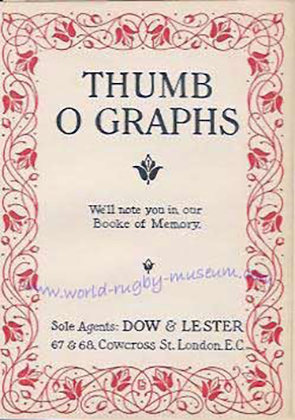

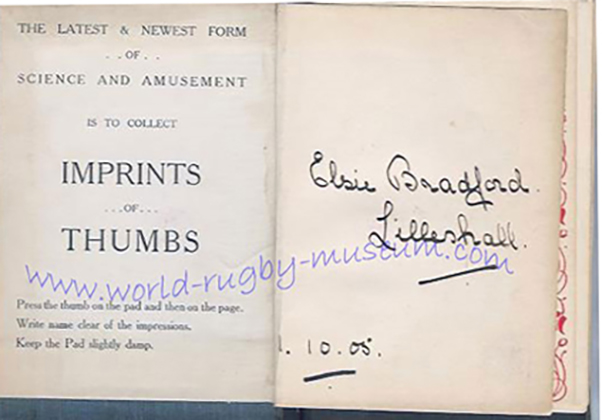

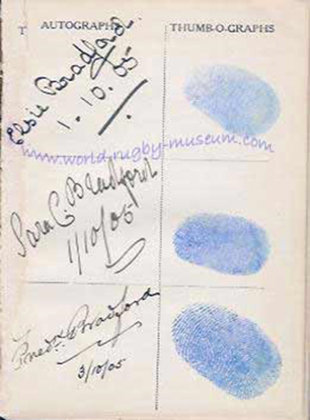

Reuben’s uncle, John Hornby, had been storing the diamonds in his safe overnight on behalf of a friend, and intended them to be transferred to a bank the next morning. He calls the police as soon as he discovers the theft. The police quickly discover the thumbprint, but are hampered because they cannot obtain prints from anyone in the family to make a comparison. John Hornby refuses to believe that either of his nephews, the only other people who have access to the keys to the safe, could be guilty, and will not allow the police to take fingerprints of either man. However, John’s wife shows the police sergeant her Thumbograph which includes both left and right thumbprints of her nephews. Reuben’s left thumbprint in the album looks to the sergeant to be a perfect match for the one found in the safe. What is a Thumbograph? you may ask. I assumed it was a device invented by Freeman for the plot, but it turns out to be a real thing: a little book popular in England in the early 1900s used to collect thumbprints of family members and friends. Click here to see examples of Thumbographs.

There’s not really a lot of action generated from the case over the course of this book. As Jervis tells Reuben’s cousin, Martin Hornby, at one point, Thorndyke is the only one who knows what the defence will be in Court, as Thorndyke doesn’t wish the prosecution to know any of the details and give them an opportunity to change arguments. There is action of a sort. Thorndyke is attacked three times, with increasingly devious methods. But there isn’t a huge amount of mystery. If we accept that Reuben is not the diamond thief, there is really only one character who stands out as obviously guilty. It is strongly hinted in the trial who this person might be, but he is never named. I did find this a little strange, that there was no follow-up with this character. But I guess that fits in with the book’s focus: Thorndyke is intent on establishing that fingerprint evidence might not be the overwhelming proof of guilt that the prosecution believes.

I enjoyed the story and was keen to keep reading to find out just how Thorndyke was going to prove his client innocent. The Court scenes were hugely enjoyable, building up tension quite nicely. The mystery might not be a difficult one – there is no clever twist – but it’s a well-written tale and one I’m glad to have finally read.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed Facebook

Facebook Instagram

Instagram YouTube

YouTube Subscribe to our Newsletter

Subscribe to our Newsletter

No one has commented yet. Be the first!