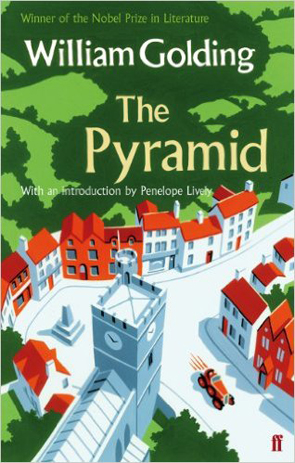

The Pyramid is divided into three sections, each relating a chapter in the life of Oliver, the novel’s first-person protagonist. In the first section, Oliver is a teenager in the 1920s who becomes involved with Evie Babbacombe after he helps her conceal her romantic tryst with Robert Ewen, the doctor’s son, from her father. In the second section he has just completed his first term in Oxford and returns to Stilbourne, his small country town, where he is pressed into service for the local drama production by his mother. In the third section, he is a married man in the early 1960s with children. He returns to Stilbourne, possibly for the last time, and hears of his old music teacher’s death.

This broad summary might make the novel sound a little disjointed. Golding initially wrote the third section of the novel and was told by his publisher that it would need something more to be a viable piece of writing. Yet Golding’s novel hangs together much better than at first it might appear, because the sections are linked by character, setting and the novel’s thematic concerns. Robert Ewen ‘borrows’ Bounce Dawlish’s car in the first section to take Evie Babbacombe to a dance, and later to have sex with her. When he accidentally puts it into a pond, Evie seeks Oliver to help them get it out. In the third section, we hear the story of how Bounce came to own the car, influenced as she was by Henry Williams, the town’s garage owner who initially relied upon Bounce’s goodwill to keep his family financially sound. For her part, Bounce desired Henry, but he only ever used her to get what he wanted. In the second section of the novel Oliver is asked to play violin for a scene onstage for the local production of King of Hearts. He has to play second fiddle (pun-intended) to Norman Claymore, the man who married Imogen, Oliver’s secret teenage crush, now playing opposite her own husband onstage. She can’t sing, but the local production is about who is who in the town and who has power. Oliver finds them contemptible. He may be studying chemistry at university, but his love is music. The third section of the novel tells the story of his studying violin and then piano under Bounce Dawlish.

My first impression of this book was that it is light and fun. For anyone who hasn’t ventured past Golding’s most famous novel, Lord of the Flies, this may come as a surprise. Some of the action is farcical, especially in the first two sections, involving Oliver’s concealments and desires, as well as his ridiculous role in the drama production in the second, recalling some of the farce of Golding’s The Scorpion God.

At the same time, the novel is deeply serious. Evie is a somewhat sad character (I wanted to write ‘tragic’, but that is not technically true, and not an honest portrayal of her). To the young Oliver she is lubricious and available: a girl whose sexual presence is felt by all; a local phenomenon,

he tells us, and every, male for miles around was aware of her.

Yet Oliver’s pride at winning her overshadows what to the reader becomes obvious but what he clearly fails to see – this is part of the skill of Golding as a novelist – that she has suffered sexual abuse, and she is only fifteen. Captain Wilmot, a war veteran tasked with teaching Evie secretarial skills, has been whipping her backside. And Dr Jones has been kissing Evie, although it is only the older Oliver looking back who makes sense of the lipstick smear on the doctor’s mouth and the real reason for Evie leaving the town.

But the real story lies with the town itself. Stilbourne is a fictionalised version of Marlborough, Golding’s own home town, and all the tropes about small hometowns apply: the rumours and spying, the exaggerated sense of social class and the desire to move on. When Oliver returns to the town in the last section of the book, he has a strong feeling that the town is unsophisticated and mendacious. It’s a feeling that merely reinforces the insights provided by the farce of the production by the Stilbourne Operatic Society in the second section. Stilbourne is society writ small, with its varying pretensions and failures represented in the parochial concerns of its people and its simply defined geography. It’s telling that the town is often described from above, from a hill where Oliver and Evie go to have sex: To the south, the erotic woods, west the racing stables, east, the college, and to the north, nothing but the escarpment of the bare downs.

As Oliver’s association with Evie grows his perception of the town changes from one of places of erotic rendezvous – the wood, the bridge – to a landscape of social and class distinction, and of shame. Oliver reflects that he has not been to the other end of Stilbourne where the Catholic Church is since he was a child in a stroller. Evie is Catholic, and it is part of the social gulf between them. Beyond Wilmot’s and Babbacombe’s cottages,

the cottages got progressively smaller, meaner, dirtier and more decayed down to the ruined mill … The boys wore the uniform of a Poor Boy; father’s trousers cut down, his cast-off shirt protruding from the seat. Mostly they had bare feet. I realised suddenly it was what the papers called a slum.

The social distinctions run through everything. The lower classes are not permitted to take part in the production by the Stilbourne Operatic Society, for instance. Imogen can’t sing, but is given a lead role, and not only because she is married to Norman Claymore:

Though Evie sang and was maddeningly attractive, she would never have been invited to appear, not even as a member of the chorus. Art is a meeting point; but you can’t go too far. So the whole thing had to rise from a handful of people round whom an invisible line was drawn. Nobody mentioned the line, but everybody knew it was there.

Music becomes a touchstone for social class and progress in the novel. Oliver can play violin and piano, but houses in the poorer part of town wouldn’t own a piano, Oliver realises. There is a certain level of education and affluence needed to receive music lessons. So, while Evie can sing, she has no formal training. It is not surprising that phonographs come to represent not only the lower classes, but the challenge to older social elites. A homeless man wheels a phonograph in a battered pram in the third section and Mr Dawlish, Bounce’s father who owns a music store, comes out to beat the contraption. When Oliver’s father plays music on a gramophone his mother describes it as cheap, nasty, vulgar, blasphemous

Later, his father advises Oliver not to see music as a profession, only as a hobby: the gramophone and wireless are going to put most professional musicians out of business.

And if the gramophone can represent this challenge to class hegemony, the novel also represents the correlative effects in the wider world. Don’t be a musician,

Bounce advises Oliver. Go into the garage business if you want to make money.

Because, despite its light tone and its farcical elements, The Pyramid represents the wider social phenomenon of class mobility, both up and down. If this were an American novel, Henry Williams, the man who comes to Stilbourne as a tenor and ends up using his garage business to own half the town, would be its hero. Instead, Henry represents an uneasy sense of change in the novel, especially since he manipulates Bounce and exploits her to further his and his family’s interests. Yet this novel is not a diatribe in defence of conservative values. Robert Ewen, the doctor’s son, stands by default at the apex of the social pyramid, but there is little to admire about him, just as Norman Claymore inspires a sense of distain. Meanwhile, Evie seems admirable – even heroic – in her honesty and desire to make something of herself, despite the judgment of others. It’s an attitude that gives rise to one of the novel’s most memorable moments. Here or nowhere

she tells Oliver who is eager to have sex with her. She means on the hill, exposed to anyone potentially looking from the town. She knows she is going. She knows what prejudices have driven her from Stilbourne. It’s a ‘fuck you’ to the town. She’s a strong character, and the only honest option is to leave. So, she chooses this. Later, Oliver says to Evelyn De Tracy, the gay director tasked with getting the Stilbourne Operatic Society’s production to work, I want the truth of things. But there’s nowhere to find it.

So Evelyn shows him a picture of himself dressed as a ballerina. It’s not what Oliver is looking for, but to a degree, it is. Like Evie, he sees through the mendacity of the town.

This is such an entertaining novel – funny with engaging characters and situations – but it also has a deeply satisfying understanding of the desires of youth and the strictures of class. I’d recommend it to anyone just for a good read, or anyone who also wanted something more thoughtful upon a second consideration.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed Facebook

Facebook Instagram

Instagram YouTube

YouTube Subscribe to our Newsletter

Subscribe to our Newsletter

No one has commented yet. Be the first!