There are some books that seem to be of a particular time and it is hard to imagine them being written any earlier. Naomi Alderman’s book The Power is one of those books. Our world, right now, reflects a need for a book like this. Recent allegations made against Harvey Weinstein in Hollywood about his abuse and harassment of women, particularly actresses whose careers were vulnerable, along with a whole raft of other prominent Hollywood stars and politicians, has revealed a culture of male privilege and abuse of power. For a long while accusations like these may have been dismissed, but now they come one after another, and it is hard to ignore the weight of evidence. The casting couch, it turns out, was not a fiction.

There has been a shift in popular attitudes, too. As a child growing up in the seventies I was aware of the dismissive attitudes to women’s liberation; of women portrayed as trouble makers and man-haters. And that’s a question one has to ask about this book. Is it a man-hating book? I think it isn’t.

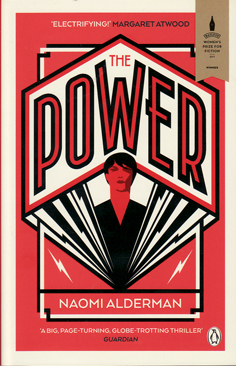

But there’s plenty in the book to point to, if one were of a certain opinion on these matters, to say it is so. Alderman sets her story somewhere in our not too distant future when women around the world mysteriously develop the power to draw electricity from their bodies and to control it. Women are suddenly dangerous. If pushed, they can hurt or even kill with just the power emanating from their hands. There is a cultural shift. The balance of power turns. The norms of patriarchal society are challenged. Roles reverse. Men become increasingly subservient to women. Men suffer violence from women. Women abuse their power. Men are raped – skilled use of a woman’s power can force men into erections against their wills – and laws are changed that make men without the patronage of a woman at risk.

If this was a man-hating book, the kind of accusation I’m sure would have been levelled at it forty years ago, then all this would seem like a kind of fantasy-wish fulfilled. But it doesn’t read like that. Alderman is clever enough to show that it is not men who are the problem, per se, but power itself and its corrupting influence. Power in the hands of women is as potentially devastating as any ever held by men. To know that is to also know that it is our humanity, not gender, that should define us: Children are born so small. It does not matter if they are boys or girls. They are all born so weak and so powerless.

As I read the book I was struck by the number of other texts of which I was reminded, which showed that Alderman’s book is really only the latest incarnation of an old theme. Aristophanes The Assemblywomen, a play written over two thousand years ago, in which women assume the control of government and enact reforms for equality, shows that Alderman’s premise is nothing new. The idea of women gaining power with which to subvert male paradigms has become increasingly popular in literature and film since the seventies. I was reminded of Stephen King’s Carrie, a girl gifted with incredible powers of telekinesis after she gets her first period. Or Joss Whedon’s Buffy The Vampire Slayer, which not only had a super-strong woman as its main protagonist, but its series end sees women around the world inheriting strength commensurate with Buffy’s.

Even when I was as young as seven I remember reading Roald Dahl’s The Magic Finger, in which a girl has the power to change reality with the power emanating from her finger. She turns a family of hunters into ducks who are then pursued by ducks transformed into a humanoid form, toting shotguns.

Alderman, herself is conscious of her antecedents. When hunted by women in the wilderness, Tunde, a reporter trying to follow the phenomenon of women’s power wherever he can, remarks to Roxy, a woman who has helped save his life, This also has been one of the dark places of the earth.

The line is straight from the beginning of Conrad’s Heart of Darkness, except now the line ironically reflects the corrupting force of power over humanity itself.

There is also Alderman’s debt to Margaret Atwood. Atwood’s dystopian The Handmaid’s Tale makes the same point a little differently. In her world of Gilead women are repressed and forced to bear the children of their Commanders. In Atwood’s world women are defined entirely by their bodies. Aldernman takes the premise a step further by weaponizing women’s bodies with their power held in their newly developed skein, somewhere near their collarbones. But Aldernman questions a world defined by binary opposites.

Alderman’s novel also gives a nod to Atwood through her use of metatextual frame. The novel begins and ends with a series of letters written between Naomi and Neil, existing far into the future. Like Atwood, Alderman uses the metatextual frame to load the sting. It is her normalising of this inverted reality that makes it seem so horrifying, and is thereby able to cleverly reveal the injustices meted out historically, and in contemporary circumstances, to women.

To that end, the book also reminded me of Orwell’s Animal Farm. The pigs, like the other animals, are repressed until their little revolution turns Mr Jones out. But their abuse of power doesn’t make us admire them for having done it. What we see is the danger in ideology and the temptation to self-aggrandisement. Alderman’s character, Allie, who calls herself Eve, is no Napoleon, but her manipulation of the old credos of religion is just as self-serving and potentially as dangerous.

I suspect that this is a book that will be more popular among women than men. If that is true it is a bit of a pity. It’s well written and entertaining. Most of its main characters are women, but so what? A lot of men will read it and understand the point. But where it really might challenge thinking, with men who probably should read it, I suspect it won’t find an audience. The book is really a part of a long ongoing argument in culture. I don’t think it is anything original and Atwood’s influence is evident. But it is worth a read and it certainly makes obvious the commonplaces that feminist writing strives to challenge.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed Facebook

Facebook Instagram

Instagram YouTube

YouTube Subscribe to our Newsletter

Subscribe to our Newsletter

No one has commented yet. Be the first!