This is a playful book. It gives the impression that the writer is having fun and enjoying poking fun at his own genre and fellow writers, and of the whole idea of amateur detectives solving murders. The Poisoned Chocolates Case is Berkeley’s fifth mystery to feature his main detective, Roger Sheringham. After being involved in four previous cases and writing a mystery novel, Sheringham has founded a ‘Crimes Circle’, an exclusive group focussed on discussion of all aspects of crime. At the start of the book, Sheringham introduces Chief Inspector Moresby of Scotland Yard to the group, with the idea that Moresby will give them all the details of a recent crime that has Scotland Yard baffled. Each member of the group will then in turn attempt to solve the crime. This will be a change from their normal discussion of historical crimes.

At the same time that he was writing this book, Berkeley was in the beginning stages of forming the Detection Club, a club he and Dorothy L. Sayers founded in 1930 to provide a social network and support system for mystery writers. In 1928 Berkeley laid the foundations for the Detection Club by hosting dinners for his fellow writers at his home. By 1930 these dinners had morphed into the formal Detection Club. It does not appear, however, that Scotland Yard ever asked the Detection Club to have a go at solving a murder for them, but there was one collaborative effort where six members wrote stories featuring a ‘perfect murder’ which a recently retired Superintendent then reviewed and gave his opinion as to whether the schemes were really foolproof (Six Against the Yard, published 1936).

The actual murder in The Poisoned Chocolates Case is a strange affair. Sir Eustace Pennefather receives a box of chocolates, mailed to him at his Club, ostensibly a free sample from a well-known chocolate manufacturer. Sir Eustace is irritated at this, and gives the box to another member of the Club, someone he just happens to be talking to as he opens the package. This man, Mr Graham Bendix, gives the box to his wife. He eats several of the chocolates himself, while his wife eats about half the box. Bendix becomes seriously ill later in the day, but recovers. His wife also becomes ill, but with her larger dose, dies. The chocolates are then found to be poisoned. The assumption is that Sir Eustace, a well-known playboy, was the intended victim as it was pure chance that led to the Bendix’s eating the chocolates instead of Sir Eustace, but no motive is readily apparent. The only physical evidence in the case are the uneaten chocolates, the wrapping paper and a covering letter. This is the case the Crimes Circle sets out to solve.

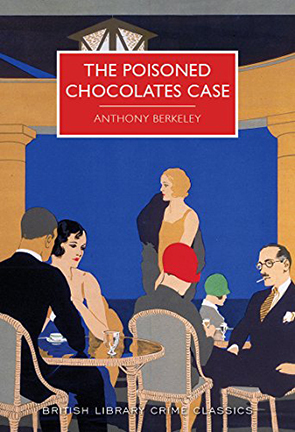

They take a week to pursue their individual investigations, then each of the six members presents his theory, one per night. As originally published, the story ends with the sixth solution. In 1979 the book was republished in America with an additional chapter, with a new solution. This was written by Christianna Brand, another Golden Age writer, elected to the Detection Club in 1946. Then, in 2016, the edition I read was published as part of the British Library Crime Classics series with yet another solution, this time written by Martin Edwards.

So there’s the set up - six criminologists taking it in turn to present their ideas about the crime, each coming up with a different solution. Each solution is ingenious and could conceivably be correct. Each, if presented in a mystery novel as the solution by the detective, would be completely acceptable as the solution. As an exchange between two members notes at one point, “…a favourite trick of detective story writers … simply made a strong assertion unsupported by evidence or argument … Just tell the reader very loudly what he’s to think, and he’ll think it all right.” But then we turn to the next chapter and someone immediately points out the errors in the previous solution and gives an equally plausible solution. It’s all great fun, with each story building on the previous one. And each of our ‘detectives’ manages to come up with some useful evidence, even if sometimes they misinterpret the meaning of what they have discovered.

Is the actual solution really important to the story? The simple fact that two additional solutions were later added suggests that the one originally given as the ending of the book is no more correct than any of the previous solutions. What seems to be more important is the insight it gives into how detective stories are crafted; that Berkeley has given us a look behind the curtains to show us how it was done.

Each solution is plausible. The first few are fairly standard solutions, typical of what you’d find in many mysteries. But as we progress, they get more and more ingenious. And the subsequent puncturing of each solution gets funnier and funnier. Berkeley ends on a good note, with a great solution. While it was fun to have two more solutions following the original ending, you could also happily end your reading without going to the last few chapters, satisfied that Berkeley had finally given us the correct solution.

I don’t think there is any great merit to Brand’s solution. The style of her chapter is out of keeping with the rest of the book and her solution seems a little jarring, following the very satisfying solution Berkeley leaves us with. Edwards manages the assignment better. Unlike the previous solutions, he doesn’t first dispose of Brand’s solution. He simply ignores it and picks up neatly as if it didn’t exist. This is easily done, as Brand’s chapter is in a different format to the earlier solutions. Rather than present a new solution to the group, she uses a conversation between one the members and a new character to give us the new solution. Edwards manages to write consistently with Berkeley’s style, and his solution provides a great ending. He finishes up with Chief Inspector Moresby admitting to the group that Scotland Yard has, after all, solved the mystery and has made an arrest. And even better, the murderer has confessed, so it doesn’t seem likely that a future writer will be able to easily add yet another solution to those already given. Edwards also adds a nice little Easter egg in his solution, giving Berkeley’s real name as the murderer.

This is an entertaining and original mystery to read. Berkeley is a clever writer with a good sense of humour, and he has given us a clever murder mystery. Of course, I formed my own solution as I read. It turns out my idea was the same as the fourth solution given by Berkeley, so I had to suffer through my idea being completely debunked. Highly recommended.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed Facebook

Facebook Instagram

Instagram YouTube

YouTube Subscribe to our Newsletter

Subscribe to our Newsletter

No one has commented yet. Be the first!