The advertising blurb on the back cover of my copy of The Noise of Time promotes the book as something of a thriller. A man

waits by a lift in a Leningrad apartment block to be taken to the Big House

from which few ever return. The front cover features an illustration in the style of a lino print, blocky and bold, depicting a man with a brief case and sun glasses, turning to look behind, wary, perhaps paranoid, suggesting a spy thriller. In truth, Julian Barnes’s novel is neither of these things.

The man

in question is the Russian composer Dmitri Dmitrievich Shostakovich. The novel is based upon his life and his work in Stalinist Russia and the succeeding years during which Shostakovich is essentially forced to join the Communist Party against his principles. The first part of the novel – there are three parts – recalls the period in which Shostakovich fears he may be arrested and executed for falling foul of Stalin’s regime. He is a successful composer and his opera, Lady Macbeth of Mtsenksk, has played both in Russia and abroad to critical acclaim. Its success has brought it to Stalin’s attention. Now, Shostakovich is ordered to attend a performance. Stalin will be there. On the night Stalin’s presence is signalled by a curtain behind which he remains hidden. Unfortunately, Stalin’s box is situated above the percussion and brass sections of the orchestra, and when the woodwind and brass sections take it upon themselves to play louder than they are meant to, the orchestra’s nervousness sends the music spiralling into a cacophonic mess. Stalin leaves before the performance has ended. A review titled Muddle Instead of Music

appears in Pravda condemning the opera’s musical quacks and grunts and growls

which are deemed politically suspect. The music, it is asserted, did not cater for the honest Russian Proletariat, but tickled the perverted taste of the bourgeois with its fidgety, neurotic music.

The review signals not only the death of Shostakovich’s opera, but quite possibly his career. At first he wishes to appeal against the review, but soon realises it will be wiser to instead apologise for his work. A friend, Marshal Tukhachevsky offers to write a letter in support of his work, but he is soon arrested and later executed.

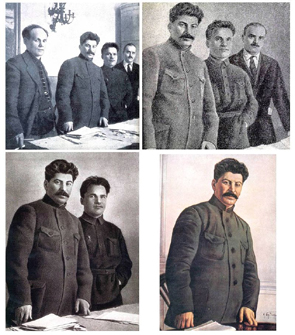

It would appear that Shostakovich received more than a bad review. The seriousness of the situation is typical of Stalin’s reign in which many people were arrested, disappeared, were executed or forced to work in labour camps – gulags – for displeasing Stalin’s regime. Shostakovich fears being erased entirely, not just by his death but from the historical record. It was common for those out of favour with Stalin to even be removed from photographs. Stalin had absolute power over life and death. There is an anecdote in the novel in which Khrennikov, Stalin’s First Secretary of the Union of Composers, shits himself in Stalin’s presence, he is so fearful. That is why we find Shostakovich waiting by the lift in his apartment block in the middle of the night, holding his brief case as the cover depicts: not because he is a spy in a spy novel but because he now fears for his life. So he stands there like many awaiting arrest, hoping that by separating himself from his family who lie asleep in the apartment, that they might escape internment, or that his child Gayla might not be taken from them. He clutches his bag with a few essentials to convince himself that his separation from his family will only be brief.

Barnes dramatizes the nexus between art and ideology. The western notion of Romantic expression – the idea that art is personal, a reflection of the inner soul (an artistic ideology itself born from Enlightenment thinking and the political ructions of the French Revolution) – is revealed as a naivety. Under Soviet ideology art, in this case music, is a process which belongs not to the individual but the people (ART BELONGS TO THE PEOPLE – V.I.LENIN

); intended not for an elite who might understand the composer’s intent, but the masses in need of a tune to hum after a day labouring for the state. Music may be written in private to answer an inner artistic vision, but if it is ever to be performed it must first be assessed by the party and approved as ideologically sound. Under a system like this the obvious dangers to one’s body are compounded with the more existential threat posed against one’s intellect and soul. The party, recalling Orwell’s satire of soviet Russia in Nineteen Eighty-Four, requires not just lip-service to its ideology, but complete belief.

This is the real danger Shostakovich faces. Many times, he reflects, had he the courage to die he would be better off; had he been marked for execution he would not have to face the moral conflicts long imposed upon him or the compromises of old age. The true danger is to his art – the artistic avenues he is forced to avoid or the possibility that his music will be forever forgotten – to his reputation, and to his own sense of self. His sense of self is twice under attack in the novel. First, Stalin rings him to request (order?) him to represent Soviet Russia on a tour to America. Later, Pospelov demands he join the party in order that Shostakovich qualify as a chairman for the Russian Federation Union of Composers, a position he cannot refuse.

Ultimately, Barnes’s novel is a meditation upon art, itself. At one extreme is the art of the party, forced into the service of ideology, which elides the individual. At the other is a conception of art purified of its historical and biographical associations, enduring above the noise of time

, the ideological and historical intersessions which alienate us from a pure experience of art, itself. In the first instance, art is an instrument, while the second remains a naïve hope against the overbearing power of exterior judgment: Art is the whisper of history, heard above the noise of time.

Art, Barnes seems to suggest, has an eternal quality that supersedes the artist and the vagaries and fashions of changing leaders and ideologies. Shostakovich, however, who must endure Soviet repression, wonders whether this can be so.

In Nineteen Eighty-Four Orwell focussed upon the breaking of the human spirit through the manipulation of language and information. One could make many comparisons between Barnes’s novel and Orwell’s. Winston Smith is entirely broken by Big Brother. Barnes’s novel also possesses that terrifying possibility, made all the more compelling because it is based on a real composer; its intention is not satirical. But I think there is also a hopefulness in this work. There is a vast difference between music and noise, and Barnes seems to suggest that as time goes on, music is heard louder and louder over that noise.

I thought this was a highly accomplished novel that delves not only into the repressive nature of politics and ideology, but examines the limits of human dignity, conscience and the soul. As such, it not only documents a terrible moment in history, but delves into philosophical questions about our humanity. Highly recommended.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed Facebook

Facebook Instagram

Instagram YouTube

YouTube Subscribe to our Newsletter

Subscribe to our Newsletter

No one has commented yet. Be the first!