Novels are all so full of nonsense and stuff; there has not been a tolerably decent one come out since Tom Jones, except The Monk; I read that t’other day; but as for all the others, they are the stupidest things in creation.

Jane Austen, Northanger Abbey, Chapter 7

If you’ve never read about Romanticism but you know you like your romance books kind of sexy or sweet, or if you’re into romantasy with different creatures doing it for each other, presumably, making each other happy (at least that’s the intention); or you think Jane Austen’s great, and whenever you enter a bookshop you find yourself gravitating towards those shelves labelled ‘Romance’, weighted with volumes about happy fluttering hearts; then picking up a copy of The Monk – having been persuaded by its subtitle, ‘A Romance’, and then having read it and then checked back on the title page, just to be sure (presuming you haven’t already abandoned it in confusion) – the next thing you are likely to do is say “WTF?” or words approximating that acronymic meaning.

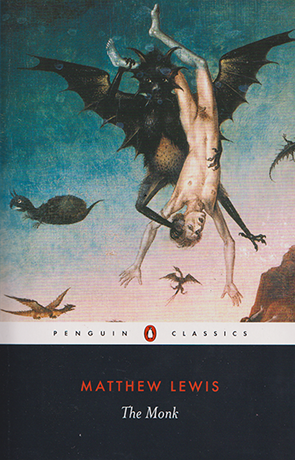

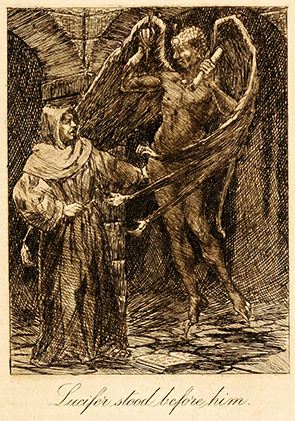

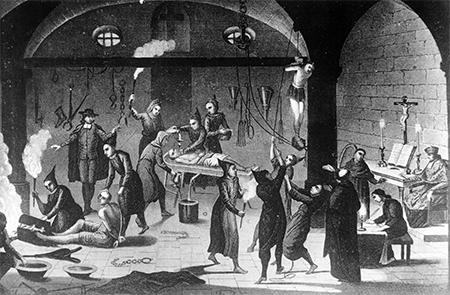

The Monk drew some criticism in its day. It shocked audiences with its sexual content, its immoral characters, as well as its representation of religion. Its main character, Ambrosio, the titular monk, is a rapist and a murderer. His offsider, Matilda, who has infiltrated his monastery by impersonating a novice by the name of Rosario, is a temptress in the classic style of women who lead good men down dark paths, ever since that thing in the Garden. To add to her resume, Matilda is into the dark arts, sealing a pact with the Devil, himself: so, a kind of girl Faustus. And then there’s the prioress, head of the order of nuns living in St. Clare nunnery, across the other side of a cemetery from the monastery where Ambrosio has recently been promoted to the position of abbot. The cemetery itself is full of cool subterranean vaults and dungeons where Agnes, a sweet but erring nun – of course, ‘erring’ here means she had sex and fell pregnant – can be locked up and tortured by the prioress and her cronies, because that will be better for Agnes’ soul. The prioress and monk are leading religious figures in Madrid, yet they both perform heinous crimes: Ambrosio in the service of his own desires, and the prioress in the purported service of morality. Relationship untainted by rape, murder, torture or simple opportunism are rare in this novel. When Matthew Lewis subtitled his work ‘A Romance’ he didn’t mean some kind of equivalent to Miss Elizabeth marrying Mr Darcy. This is not that kind of romance. Besides, Pride and Prejudice hadn’t even been written yet. The Monk is what is more commonly understood as Gothic Fiction, and if it was adapted for the screen now, it would most likely fall into the horror genre for purposes of marketing, with an emphasis on the exploitative sexual elements of the story, and the supernatural. Remember that pair of movies, The Nun and The Nun II? The Monk comes with its own creepy nun, Beatrice, the ghost of a bleeding nun who scares the bejesus out of people, and whose origin story will be revealed as the novel progresses. Beatrice has been murdered by her lover, but she is also a murderer.

Critical Responses to The Monk

The Monk was considered pretty racy back in the 1790s which made it a best seller. But it drew some harsh criticism, especially from a piece by Samuel Taylor Coleridge, published in The Critical Review in 1797, and later, another response written by Thomas Mathias in The European Magazine. Coleridge both praised Lewis’ talent as well as criticised the novel for moral and religious reasons. Of particular concern for Coleridge are observations made about the Bible in chapter seven. Ambrosio observes Antonia reading the Bible while he is in her house as her mother’s confessor. This is the sweet desirable innocent Antonia whom he intends to deflower, just as soon as he can get past her mother, Elvira, and an inconvenient door lock, without damaging his reputation as the most pious and upright religious leader in Madrid. Ambrosio finds it difficult to believe that Antonia can be so ignorant in matters of sex. After all, he observes, the Bible is full of,

… narratives [that] can only tend to excite ideas the worst calculated for a female breast: every thing is called plainly and roundly by its name; and the annals of a brothel would scarcely furnish a greater choice of indecent expressions.

This opinion is also shared by Antonia’s mother, who has limited Antonia’s reading of the Bible and has “copied [it] out with her own hand, and all improper passages either altered or omitted.” Elvira’s expurgated version of the Bible, while well intentioned, only reinforces for the reader the opinion expressed in support of Ambrosio’s darker motivations.

Coleridge found the remarks about the Bible in chapter seven most inappropriate, even though he praised the section about the bleeding nun as “truly terrific” and the representation of Matilda as “the author’s master-piece”, even though both characters are of questionable moral status. I think Coleridge understood the appeal of the supernatural and its power to embellish a tale. His most famous poems, yet to be published, ‘Kubla Khan’ and ‘The Rime of the Ancient Mariner’, had supernatural elements. Coleridge even published a poem about a murderous monk only a few years after Lewis’ novel was released. Even so, the remarks about the Bible were a step too far and drew Coleridge’s ire:

We believe it not absolutely impossible that a mind may be so deeply depraved by the habit of reading lewd and voluptuous tales, as to use even the Bible in conjuring up the spirit of uncleanness. The most innocent expressions might become the first link in the chain of association, when a man’s soul had been so poisoned; and we believe it not absolutely impossible that he might extract pollution from the word of purity, and, in a literal sense, “turn the grace of God into wantonness”.

Coleridge’s position makes it clear: he associates the remarks about the Bible with the opinions of the author, himself. These days some people may find Lewis’ position against the Bible offensive, but I believe a modern reader is more likely to damn Ambrosio’s crimes, rather than the author or the novel as a creative expression. Today, authors are treated as separate from their characters and narrators, but not so in the 1790s, and maybe in this case with some justification. There are certainly instances when Lewis speaks directly to the reader, or allows characters to express his own feelings. In the opening chapter, when Antonia’s aunt Leonella flirts with Don Christoval, we are reminded of Antonia’s innocence with a following quip that is unmistakably the author speaking directly to us:

Now Antonia had observed the air with which Don Christoval had kissed this same hand, but as she drew conclusions from it somewhat different from her aunt’s, she was wise enough to hold her tongue. As this is the only instance of a woman ever having done so, it was judged worthy to be recorded here.

‘You understand what women are like,’ Lewis seems to be saying to us with a pint of his local’s best bitter resting in his hand and a leery wink to punctuate the joke. This strong connection between the voice of the author and the text is reinforced when the narrative digresses and Lewis speaks about the lot of authors through his character, Raymond, the Marquis, who tells Theodore, his companion who has written a poem: “to enter the lists of literature is wilfully to expose yourself to the arrows of neglect, ridicule, envy, and disappointment”. He continues by bemoaning the unfair treatment of “all [who] conceive themselves able to judge them.”

Thomas Mathias, the second consequential critic of the novel, understood this strong association between author and text, and set upon the author’s personal reputation, especially since in a second edition of the novel Lewis had revealed his identity and the fact that he was a Member of Parliament. Mathias argued that there needed to be a higher standard set by people of influence and authority in society: “Reformation must begin with the GREAT, or it will never be effectual. Their example is the fountain from whence the vulgar draw their habits, actions, and characters”. And he went further than Coleridge upon the matter of religious representation. He argued that Lewis,

has neither scrupled nor blushed to depict and to publish to the world the arts of lewd and systematic seduction, and to thrust upon the nation unqualified blasphemy against the very code and volume of our religion.

The word ‘blasphemy’ was a serious accusation and Lewis knew he would potentially end up in court. It is unclear whether any legal action was taken against him, but by 1797 Lewis produced a rewritten version of The Monk which avoided any potential blasphemy. In later editions, he continued to soften the immorality of the tale.

The Monk and Religion

The fact is, Lewis later claimed he had nothing against religion, but the position against religion in the novel is not one dimensional, and it is integral. The prioress acts out of a misguided sense of morality, Elvira has essentially come to the same conclusion about the Bible as Ambrosio, though she acts within the moral values of society and the church, and Lorenzo, who is as close to a hero as the novel comes, is also ambivalent about religious observance, which he equates with superstition.

Universal silence prevailed through the Crowd, and every heart was filled with reverence for religion. Every heart but Lorenzo’s. Conscious that among those who chaunted the praises of their God so sweetly, there were some who cloaked with devotion the foulest sins, their hymns inspired him with detestation at their Hypocrisy. He had long observed with disapprobation and contempt the superstition which governed Madrid’s Inhabitants. His good sense had pointed out to him the artifices of the Monks, and the gross absurdity of their miracles, wonders, and supposititious reliques. He blushed to see his Countrymen the Dupes of deceptions so ridiculous, and only wished for an opportunity to free them from their monkish fetters.

Lorenzo’s contempt is not for Christianity in general, but Catholicism in particular, since Spain is a Catholic country during the period of this novel, as it remains now. It is the artifice, miracles, wonder, relics and other stagecraft of religion that Lorenzo rejects, as manipulative and misleading. That, and the hypocritical corruption of the church, exemplified by Ambrosio and the prioress, which is a criticism going back to Martin Luther. Lewis’ audience was essentially an English audience, and characters like the monk and the prioress who preside over Catholic institutions, are weighed against characters like Lorenzo and Agnes, who are also guided by their desires, but who are essentially Protestant in their thinking. Agnes has become a nun, but she does not wish to be a nun. She was forced into a nunnery to fulfil a superstitious promise made to God when her mother was sick. Now, she wishes to marry Raymond, the Marquis, with whom she has fallen pregnant. Likewise, Lorenzo is a character guided by desire, but willing to bow to convention. He speaks to Elvira about his interest in her daughter and agrees to seek the permission of the duke, his father, in order to get Elvira’s blessing for the marriage, too. After all, Lorenzo is somebody of status while Antonia is just an ordinary citizen, so he understands the conventions of class and Elvira’s concerns. Lorenzo’s is a morality driven by character and convention, while Ambrosio’s depredations seem to be the product of a Catholic system in which he has been raised: wherein he has been shielded from desire and temptation until the moment of his promotion, when he must then engage more directly with the wider world, which threatens to expose the weaknesses in his character and the system which has protected him.

Women in The Monk

The epigraph to the first chapter of The Monk is a quote from Shakespeare’s Measure for Measure which recalls the depredations of Lord Angelo. Lord Angelo, who has taken charge of his abbey in the absence of the duke, is a man who denies his own feelings and desires. Yet Angelo, when the beautiful Isabella begs him for her brother’s life, uses the leverage he has to manipulate her and press her for sex. The epigraph is an ominous foreshadowing of Ambrosio’s baser instincts in Lewis’s novel. And Isabella is like Antonia, though her fate is happier. She represents women who are to be revered for their purity and chastity.

Lewis’ quip against women (“the only instance of a woman ever having done so”) would seem to provide a clear path for a feminist appraisal of the novel. Women in the novel can be represented on a spectrum. At one extreme they are either entirely innocent and pure like Antonia, or tainted by sex like Matilda. Matilda is sexed in the extreme. She seduces Ambrosio. She is lustful. She is a cross between an insatiable Lady Macbeth and Faustus. Then there is Leonella who is sadly aging and unmarried, so it is easy for her to delude herself that Don Christoval has an interest in her, or that another young man finds her attractive when she inherits money. The prioress’ crimes parallel Ambrosio’s, though they are committed to repress the sexual instincts of her nuns. Agnes, the sister of Lorenzo, has fallen pregnant to the Marquis. From a modern perspective, Agnes and the Marquis’ relationship is the most normal and healthy in the book, except that they exist within a system and culture which suppresses natural feelings. That they have an equal expression of love between separates them from the violent and murderess passions that rule characters who suppress their own feelings or those of others. To this extent, The Monk is critical of Catholicism, widely associated with superstition in Protestant England: ranging from the ghosts and spirits of this world and the arcane practices used to summon them, to the more conventional Catholic practices, like abstinence for its clergy, and confession, which exposes Ambrosio, cloistered in his monastery since birth until his recent promotion, to the nuns of the nearby priory who will see him for absolution. This is Spain of the Spanish Inquisition, a period in which institutional violence was employed for the purposes of religious conformity. That Ambrosio commits rape and murder is antithetical to the precepts of the system while his methods are, ironically, in keeping with its suppressive practices. As a Catholic monk, Ambrosio cannot simply love a woman; he must secretly imprison her and use force against her.

It is interesting, then, to compare the major female characters of the novel. If we return to the idea of a spectrum where, at the left, we have total innocence and purity, and to the right we have total depredation and evil, we may place Antonia to the left, a young girl shielded even from the salacious passages of the Bible. To the right on that scale, we would find Matilda who has entered the monastery with the intention of seducing Ambrosio. She summons demons to her will and encourages Ambrosio ever closer towards damnation. The extent of Matilda’s deliberate targeting of Ambrosio is well exemplified in the religious portrait of the Madonna which stirs Ambrosio’s desire. Matilda was the model for the portrait, and she takes delight in hearing that Ambrosio admires it. It emboldens her to target him. Ambrosio has gazed upon the portrait for two years with increasing heat, and he tries to convince himself that he admires the perfection of the Virgin and the painter’s skill, rather than “the treasures of that snowy bosom!”

What charms me, when ideal and considered as a superior Being, would disgust me, become Woman and tainted with all the failings of Mortality. It is not the Woman’s beauty that fills me with such enthusiasm; It is the Painter’s skill that I admire, it is the Divinity that I adore!

Ambrosio is clearly working very hard to convince himself. We see the seeds of Ambrosio’s depredation in this denial. Through the Madonna, Ambrosio hopes to admire the ideal of woman freed from her own earthly desires and the reality of her body. But sex negates that perfection for Ambrosio. Instead of love or pleasure in sex, or even a reification of some kind of female perfection, Ambrosio seeks to corrupt what he at first reveres: “He easily distinguished the emotions which were favourable to his designs, and seized every means with avidity of infusing corruption into Antonia’s bosom.” That the portrait of the Madonna is in fact Matilda only adds to the moral irony.

On our spectrum, between these extremes of Antonia and Matilda, is Agnes, an unwilling nun, pregnant out of wedlock but hoping to achieve an honourable marriage with the Marquis. She shares some similarity with Beatrice, the nun killed by her own lover. Agnes pretends to be the ghost of the nun in an attempt to escape, for a start. Like Agnes, Beatrice had also been forced into a nunnery at an early age before she understood sexual desire. Ironically, it is the strictures placed upon her by her religious life against of her natural instincts which leads to her downfall. Upon escaping Beatrice flees with Baron Lindenburg, thereby placing herself into a situation in which she becomes a concubine. Don Raymond, the Marquis, attributes Beatrice’s moral depredations to her own depravity, but his own story contextualises her sexual relationships with the baron and his brother as deriving from the religious strictures placed upon Beatrice in her early life. It’s an interesting interlude in the novel, proving to be one of its most memorable Gothic elements: the bleeding ghost of Beatrice stalking the Lindenburg castle, now owned by Agnes’ family. But it also further teases out the moral complexities of the story, too. Agnes has fallen in love with a good man and despite the interference of the prioress and her crony nuns, Agnes’s character is therefore not warped by desire. She merely experiences a common outcome of that desire – pregnancy outside marriage – which is against the institutional interdictions of her religion. To add to this moral complexity we also have another minor character, Marguerite, a peasant woman living in a cabin with her husband, Baptiste. She, too, has something in common with the Bleeding Nun, since she stabs her husband to death. Marguerite is the victim of social strictures. Baptiste is a key member of a group of bandits in the forests outside Strasbourg, luring people to his house to kill and rob them. Marguerite is essentially a prisoner in her marriage, but she is provided an opportunity for escape when the Marquis arrives, seeking shelter for the night, unable to make it all the way to the city. Like most women in this story, Marguerite is an institutional prisoner of a kind.

The idea of entrapment and escape is common to female characters in this book. Antonia is targeted by Ambrosio, who enters her bedroom at night and later seeks to entrap her with a ploy directly out of Romeo and Juliet – to fake her death – and then imprison her in a dungeon as his sex slave. Agnes is forced into a nunnery and seeks help from her lover, the Marquis, to help her escape. Later, she is imprisoned by the over-zealous prioress in a dungeon. Beatrice, the Bleeding Nun, found herself sharing her marriage with her husband’s mistress. And Marguerite, like Beatrice, committed murder to escape her marriage.

What separates Agnes and the other women isn’t that she seems most believable to modern sensibilities – she is a young woman who accidently gets pregnant and wishes to marry her lover – but that her lover, Raymond de las Cisternas, the Marquis, of all the characters, is a man who has most absolutely stepped outside the social class to which he was born, and has not used his status and position to win Agnes’ love. In a sense, the Marquis has abandoned his traditional patriarchal role. The fates of women in The Monk are either warped by the actions of men, or by institutions representing patriarchal power. The prioress, as a leader within a patriarchal religious system, is complicit. But the Marquis seems to be an uncomplicatedly good man. True, he has the support of privilege and money, but he has renounced his social position and has adopted a public persona, ‘Alphonso d’Alvarada’, who is of a humbler social status. Raymond’s father has suggested he conceal his social rank and mix with all classes of people. So, it is not a stretch to believe that he is willing to stay in the humble cabin of Marguerite and Baptiste, purportedly a simple woodcutter. That a baroness is forced to spend the night in their cabin that night, too, as Baptiste and his associates plan to kill and rob them, is an accident that joins Agnes’ story with Antonia’s. Grateful for being saved, the baroness invites ‘Alphonso’ to travel to Lindenburg to visit the family’s castle in Bavaria. This is where he firsts sees Agnes. He falls in love with her but she insists he must win her family’s approval for marriage. After all, he appears to be of a lower status, just as there is a disparity in status between Lorenzo and Antonia. This is why the baroness – Lorenzo’s mother no less – is possibly willing (like Ambrosio forcing Antonia) to have him as a lover, and why she is so incensed at his rejection. Elevated by her social status she has perceived power over the Marquis, and so is subject to the same depredations afforded by patriarchal power.

It seems that Raymond’s apparent social class makes his use as a sexual diversion more comprehendible to her than as a likely match for her daughter. The purest unions in the novel seem to step beyond the strictures of social convention, rather than being warped by them. That Raymond’s story occupies the bulk of the first part of the novel, even though it is a subplot, is a result of his long explanation to Lorenzo as to why he is a man of integrity, despite the suspicion inspired in Lorenzo by his false identity, and that he is of a requisite status to overcome Lorenzo’s social prejudice.

The Monk in an era of Revolution

The salacious and irreligious elements of the story are what seem to be most remembered now, but this notion of status, class and position pervades the novel as much as anything, making it a novel that reflects its historical moment. Ambrosio only faces his first real test of his integrity when he is elevated to the position of abbot. The prioress holds a similar position. And the relationships between Raymond and Agnes, and Lorenzo and Antonio, meet delays because of the apparent and real disparity in their social statuses. Lewis has questioned the integrity of religion, and he foregrounds the equally questionable social structures that underpin hierarchy and behaviour. To this extent, the novel raises fundamental questions about society that the French Revolution exploded only a few years before the publication of The Monk. The Terror, which had been the unfettered response of what was a war on status and class, had continued until just before the release of The Monk. Catholicism was repressed in France and the revolutionary government tried to also suppress Christianity in general. Feudalism was abolished and many privileges formerly afforded the aristocracy were abolished, too. The most memorable moment of the revolution – apart from the guillotine and the Terror – was at its very beginning when the Bastille, a jail in Paris, was stormed by revolutionaries and its prisoners released. The prison was then demolished by the revolutionary government.

There is a similar moment in the latter part of The Monk. When the prioress’ crimes are revealed, there is a spontaneous uprising against the nunnery by citizens who have come to watch a religious procession. Many nuns are killed and the nunnery is burned. In effect, this is a judgement against the superstition the church has employed to control the population, as well as against its own hypocrisy. Though the Inquisition still exists and the Catholic church in Spain has not been overthrown, this incident reflects the uneasy feelings about status and privilege that the French Revolution exposed; of statuses and positions predicated upon an institution that The Monk reveals to be not just corrupt, but corrupting.

The French Revolution was partly the child of Enlightenment thinking: of the notion of equality and the Social Contract, of science and reason. But the revolution, in turn, was an intellectual spur to Romanticism. Romanticism was a reaction to the strict asceticism of Classicism, even against the rationalism of the Enlightenment. It privileged individual feeling and experience. It hearkened back to the Romance fiction of the Middle Ages. Artists and writers often took inspiration from nature and ruins, which reflected that period of history. Hence an interest in creating garden ‘follies’, often in the form of false ruins, by the rich of this period. Gothicism was Romanticism taken to an extreme. It’s there in the supernatural scenes of ‘The Rime of the Ancient Mariner’, when Coleridge has the dead crew reanimated to sail the ship. Yet Wordsworth and Coleridge’s Lyrical Ballads were an attempt to write for ordinary people about ordinary subjects, despite Coleridge’s much more flamboyant contributions to the book. And Wordsworth wrote about the impact of the French Revolution on his thinking in ‘The Prelude’. But in Gothic literature and art, majestic landscapes, castles, cemeteries, dungeons: these were places of mystery in which the imagination could take flight and the most extremes of feeling could find expression. Gothic is often liminal, teetering between the permissible and impermissible; a grey area of morality in which characters like Ambrosio can easily step too far. The Monk is not strictly a Romance, though its form grows from that genre. It is too dark.

If we are to understand The Monk beyond it being a nasty piece of work, of it being not very romantic in our modern understanding of that word, of it being critical of religion, but also that it offers a salacious piece of titillation, then I think the novel, past all this, has to be understood as a response to the events of the decade of the 1790s. The 1790s were a period in which the pillars of society were being questioned, and when notions of personal morality and individuality were being championed by Romantic writers. The Monk may not seem very romantic, but it is Romantic. Its setting harkens back to an older world of castles, monasteries and strict social hierarchies, but it is implicitly a modern work, in as much as the Romantic writers still inform our modern sensibilities.

Conclusion

I thought it necessary to give a little bit of context in this review for an older novel like The Monk: for modern readers who may be wondering whether they would like to read it, or for those who have read it to who are looking to read someone else’s thoughts. If you are interested in Gothic fiction, The Monk is one of a few books you should be reading from the late eighteenth century to get a start. Those include Horace Walpole’s The Castle of Otranto and Ann Radcliffe’s The Mysteries of Udolpho, as well. The Monk, in one way or another, embodies almost every Gothic trope. Walpole’s novel, nominally the first Gothic novel, is also exemplary of the Gothic genre, but it is harder to take it as seriously. While Lewis is somewhat there on the page as the narrator, The Monk captures the psychological state of its characters, and immerses its reader in the thinking of the time. We understand the stakes of transgression during this era, even though we cannot have lived them. We understand the temptations, the justifications of characters we should abhor, and this is gripping. And as the tension and the crimes mount, we can still find them believable, even though the book is full of situations that have become cliches since, or have been worn down in our collective nervous systems by their use: dungeons, clanking chains, ghosts, torture, murder. The Monk is actually a well-produced piece of macabre entertainment, as Coleridge acknowledged, and if you are of a mind to be entertained, you will be.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed Facebook

Facebook Instagram

Instagram YouTube

YouTube Subscribe to our Newsletter

Subscribe to our Newsletter

No one has commented yet. Be the first!