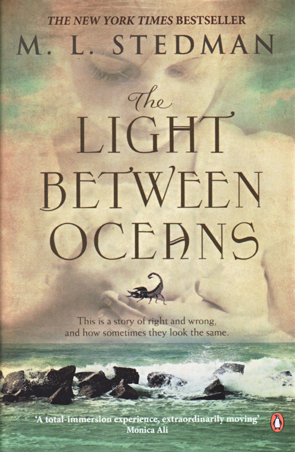

The Light Between Oceans is a tale of personal tragedy and moral ambiguity. The title of the book, multifaceted in meaning, is a clue to this. On a literal level the ‘light’ referred to is the lighthouse on the fictional Janus Island off the coast of Western Australia, situated between the Indian and Great Southern Ocean. This is where Tom Sherbourne and his wife Isabel spend several lonely years, coping with the grief of three miscarriages.

Tom, a decorated war hero, returns from the Great War haunted by all that he has seen and done, often wondering why he survived physically unscathed when the horror of war is evident all about him, in the broken bodies of the men who returned as well as the lingering grief of families whose sons remained in Europe. Isabel’s family has been hit hard by the war. She has lost both her brothers. When she meets Tom, she either falls in love or makes a pragmatic decision – able-bodied young men are thin on the ground in the small town of Partageuse – and proposes marriage to him. She embraces the prospect of a lonely life with a lighthouse keeper.

Yet life does not follow Isabel’s dreams, and after three miscarriages she questions herself as a woman. Then, miraculously, a small boat is washed ashore with a dead man and a baby, a young girl, who is very much alive. From here on the book abounds with the idea of miracles and God’s divine benevolence

– Isabel and Tom, along with their community, are God-fearing folk – and the novel’s imagery reflects a world of choices bounded by Christian sensibility. What to do about the child? Tom is bound by very strict rules that govern the running of lighthouses. Everything must be recorded. (The log is the gospel truth

). Then there is the law. They should send a signal to the coast to tell of the child’s presence. But there is also Isabel’s belief that the child balances a cosmic wrong – the three miscarriages – and that God has sent the baby to alleviate their suffering: Isabel floats further and further into her world of divine benevolence, where prayers are answered, where babies arrive by the will of God and the working of currents

. The baby is a gift

. Isabel persuades Tom to say or do nothing. The child’s mother is probably dead, she reasons. What good could telling do anyone? And besides, she has only recently buried her third child and her milk returns. They will pass the baby off as their own. So, they call her Lucy, meaning ‘light’. Tom buries the dead man.

There is little to trouble this arrangement except Tom’s conscience, and Isabel has to mount an argument to bring him into line whenever he suggests they should have acted otherwise. So, the real complication occurs during a visit to Partageuse, when Lucy is introduced to the family and is due to be christened. They discover, to their horror, that Lucy belongs to a woman they know, Hannah Roennfeldt, widow to Frank, who fled from an alcohol-fuelled mob during Anzac Day revelries. Believing he is German they taunt and then chase him. To escape, he sets out in a boat with his daughter to protect her. Tom and Isabel easily join the dots and draw a conclusion. They have done something terribly wrong.

This is a skilfully written novel that touches upon primal human emotions. Stedman’s writing is both poetic in its evocation of the spiritual struggles of its characters along with its primary moral themes, but remains unobtrusive in the level of its language and construction. What makes the story compelling is we understand the grief of the characters and the moral bind in which they find themselves. Even if we have never experienced the horrors of war or the loss of a child, we understand the presence of the past in our lives and our connections with others we love, especially children. Tom bears not only the burden of the war, but his relationship with a distant father whom he never entirely understood. Hannah, too, has had to achieve independence from a father who seeks to control her through his money.

Along with this are the religious elements of the novel, closely linked to the novel’s moral themes. Light abounds in this book, and it is not difficult to understand that sometimes it assumes a divine quality. The light is not just the light of the lighthouse. It is also a protective light that shines out equally for all who pass it. But it is a light, as is made clear, that is for others to see. It does not shine on the island. It is only away from the island, returned to church and community, that Tom and Isabel can face the moral implications of their actions. Their island is literally divorced from the Christian world. Name after the Roman god, Janus, a god of doorways who faces in two direction, it represents the moral grey area Tom and Isabel now inhabit. Their actions saved a child. They gave love to the child and a good life. But what they did was also illegal and they have created great pain for others. It is not surprising that Stedman chooses to invoke other religious tropes to play out this moral drama: Solomon’s wisdom famously rested on his decision regarding a child and competing parents.

But this is where the religious elements of the novel may play less successfully for a more secular audience. Unmentioned in Stedman’s narrative, but certainly in my mind as I read the novel, was the story of Job who is tormented and tortured by God for the sake of a bet with the devil. That story reminds us that attributing divine benevolence to the intercession of pain makes the attribution of that pain to the same power logical, also. If God provided a gift

to mitigate the loss of three children, then God logically had something to do with their loss, even if we can excuse him from everything that follows: Isabel and Tom exercised free will in keeping Lucy, but they did not when she had three miscarriages.

Some might dismiss these secular sensibilities, since this is drawing material into the novel that isn’t there. But the problem for me lay in that all the pain the characters face and all their decisions lie squarely in the secular world. Women miscarry sometimes and we are given an explanation as to how baby Lucy arrived at the island, which had nothing to do with God’s providence but the fear and prejudice of drunken men. Yet the novel seems to only intensify the spiritual attributions in its quotidian denouement. The argument here must rest between the spirituality of feeling against a real spirit with guiding intent, and I think Stedman walks that line reasonably successfully, since it is in her characters’ sensibilities that their spirits mature against grief, along with an acceptance of the past. Instead of a full choir, Stedman’s characters placate themselves with a series of homilies: You only have to forgive once. To resent, you have to do it all day, every day

; …to have any kind of a future you’ve got to give up hope of ever changing your past

.

In the end, the story’s a real tear-jerker. It hits all the right emotional beats and it explores every moral crevice a little girl with a lighthouse can shine light. This makes for a story brimming with sentimentality, but the scenario is interesting enough to be compelling and its attendant moral no-man’s-land is littered with enough moral quandaries to keep a reading group going for hours.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed Facebook

Facebook Instagram

Instagram YouTube

YouTube Subscribe to our Newsletter

Subscribe to our Newsletter

No one has commented yet. Be the first!