The King Must Die is a retelling of the early part of the Theseus myth, from the secret of his parentage, his journey to Athens and the subsequent acknowledgement by his father, Aegius, King of Athens, that Theseus is his son and heir, to his decision to become one of the tributes to Crete, finally ending with his return to Athens after slaying the Minotaur. For the full Theseus story, you also need to read the sequel, The Bull From the Sea, which covers Theseus becoming the King of Athens and his later adventures.

Renault takes Theseus out of the pages of exaggerated legend and makes him a real person from the Bronze Age. The thing that struck me the most as I read was the lack of fantasy elements. Yes, Theseus and many of the other characters believe in their gods or goddesses; that they have an influence on human affairs and take an active role in everything that happens. Renault’s Bronze Age characters look for signs and portents from their gods and superstitiously believe that any misfortune is a sign of displeasure. But in every instance, she gives a natural explanation instead of a supernatural one, and the story is one of human relationships. The most obvious example is the Minotaur, himself. In the legend, the Minotaur has the body of a man but the head of a bull. He is the product of an unfortunate relationship Minos’ Queen had with a bull. In Renault’s retelling, he is a human child, born from an adulterous relationship the Queen had with a bull dancer. An ornate bull’s head is worn by the King in ceremonies, as the bull is the emblem of the royal family.

One of the things Theseus realises is wrong with the Minoan society is that “their rites have grown frivolous and like play.” The Bull Dance, the thing that he and all the other tributes are brought to Crete to perform, started as a sacrifice to Poseiden, a way to placate the god who was thought to live deep under the earth in the form of great black bull. The Bull Dance began as an honour to perform and ultimately to be sacrificed: it has now become a sport, performed by the tributes for entertainment of the ruling class. The idea of a willing sacrifice is repeated many times in this story.

But I’m jumping ahead if I start with Theseus in Crete. He doesn’t get there until the fourth section of the book. Before that we read about his formative years, as he struggles with the uncertainty of his parentage. His grandfather is the King of Troizen, his mother a priestess. But he does not know who his father is, and this uncertainty leads to him constantly needing to prove himself. One of the stories of his birth is that he was fathered by Poseidon, and throughout his life, Theseus believes that the god speaks to him. When he is seventeen his mother finally reveals who his father is by taking him to a huge stone and telling him to lift the stone. This part of the story gave me strong Arthurian legend vibes. Theseus is conceived in secret, raised not knowing his father, and finally has to prove himself worthy by an impossible physical task, lifting a huge boulder to find a sword instead of drawing the sword from the stone. Theseus then has to use his wits to survive on his journey to his father in Athens, with many of his encounters reinforcing the lesson he first learned from his grandfather, that the king must always be prepared to sacrifice himself for his people.

Finally, his journey culminates in his truly becoming the leader of his small group of fellow tributes (they call themselves the Cranes). Theseus believes that he has an obligation to protect and care for them, and to sacrifice himself for them if necessary. To him, consenting to make the sacrifice is an important part of who he is: “It is not the bloodletting that calls down power. It is the consenting.” In an earlier section of the book, in Eleusis, he doesn’t feel obligated to following the customs and fights back against what seems to be his fate: death at the end of a year. In his mind, he did not consent to become the sacrifice, he was forced into the role, and he actively works against those who seek to force the sacrifice upon him.

By the time Theseus and the Cranes arrive in Crete, Minoan society has reached the stage of decadence. The ruling class seem to live only for pleasure, and pay only lip service to their gods and rituals. The King is largely absent from his people and does not concern himself with them, which gives his stepson – Asterion, also known as the Minotaur – the opportunity to try to seize power. But Theseus understands that Asterion wants power solely for the sake of having power:

Any man will want power to get what he desires: glory or lands, or a woman. But the man wanted it for itself, to put down other men, to fatten his pride with eating theirs like the great spider that feeds upon the lesser.

He thinks he can rule without the sacrifice. Theseus uses the decadence of the Minoans and the resentment felt by the common people of Crete to overthrow the Minoans and to ensure that Athens will never again send its youth to be sacrificed for entertainment.

This was a highly entertaining book to read, one that gave me a feeling of what it would be like to live in a Bronze Age society. Highly recommended.

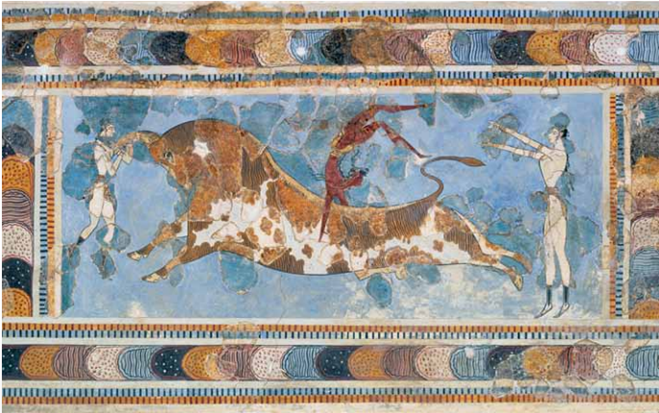

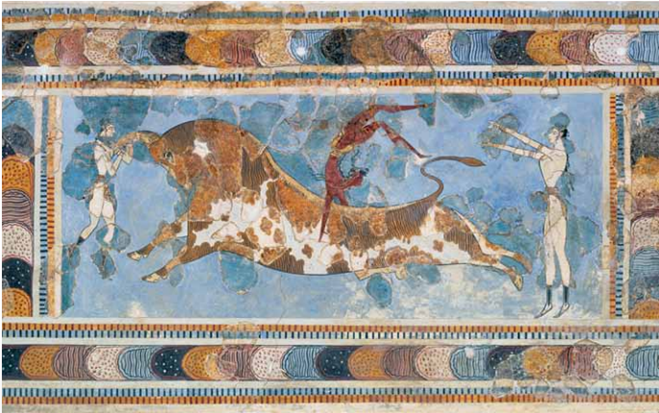

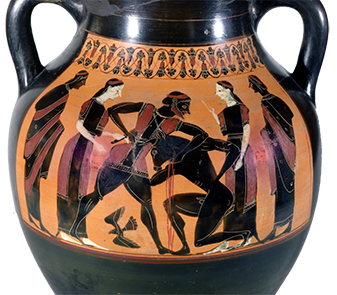

Bull-leaping fresco from the east wing of the palace of Knossos (reconstructed), c. 1400 B.C.E., fresco, 78 cm high, in the Archaeological Museum of Heraklion

This is a composite image, constructed from at least seven different panels found at Knossos by Sir Arthur Evans who excavated the site from 1900 to 1935. The painting shows three people leaping over a bull: one person at its front, another over its back and the third at its rear. Minoans were known to have used ancient Egyptian gender-colour conventions, with white indicating a female figure and brown indicating a male.

This image depicts a typical bull-dance done by Theseus and his fellow tributes in The King Must Die, where one dancer would be chosen to leap over the bull while another waited to catch him at the end of the leap, and other dancers held the bull steady by his horns.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed Facebook

Facebook Instagram

Instagram YouTube

YouTube Subscribe to our Newsletter

Subscribe to our Newsletter

No one has commented yet. Be the first!