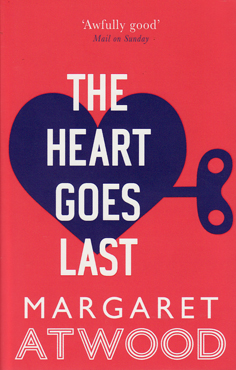

Towards the end of The Heart Goes Last, Jocelyn says to Charmaine in a remarkably upbeat ending, So, joy and fresh days of love.

It’s a slightly odd thing to say, and if we’re not already alert to that, our attention is drawn to the line by Charmaine who thinks it’s weird, too. A vigilant reader should suspect that Atwood has borrowed the line from the Bard himself. And so she has. It’s a line spoken by Theseus in the last scene of A Midsummer Night’s Dream. This shouldn’t be surprising. The book is littered with allusions to the play that become more obvious as the structure of the story is revealed. And besides, one of the three epigraphs to the book is a quote from the play concerning the insights of lovers. Another is from Ovid from the story of Pygmalion and Galatea (although she wasn’t actually given that epithet in Ovid’s original version) In doing this Atwood forthrightly identifies the literary nature of her writing. But does this affect our reading or understanding of her story?

I read Atwood’s Hag-Seed last year which is based upon Shakespeare’s The Tempest. That book was written as part of a project with other writers for the Hogarth press. The story is set in a prison and has as its Prospero a stage performer whose role as artistic director of a drama festival has been usurped. He resorts to teaching an acting course in prison and from there he plots his revenge. The broad parallels to Shakespeare’s plot are obvious. However, I thought Atwood’s retelling added little to the play, and while knowledge of the play allowed a reader to nod knowingly at the progression of her plot, there was something laboured in the writing, I thought. Perhaps I mean constrained.

So, as I progressed through this story and it became more and more obvious what Atwood was doing, I had to ask myself that question: does understanding these allusions and structures bring anything more to the story than it might have already had?

Before I consider that question, a bit on the story itself. Stan and Charmaine are the protagonists. They exist in a version of our own world sometime in the near future when another financial crisis has hit. Up to fifty per cent of the population is unemployed. The impression at the beginning is that this is going to be a story of a dystopian future. It is. Stan and Charmaine, like many others, have lost their home. In fact, they are better off than most. They still have a car and Charmaine still has a part-time job. But being homeless, they must avoid the desperate hordes and criminal gangs who will either steal from them, rape them, kill them, or perform some combination of these. There is a slight sense of Mad Max in all this. So, The Heart Goes Last has all the hallmarks of that kind of dystopian story. But this is nothing like the MaddAddam trilogy or The Handmaid’s Tale. This is not a meditation on the breakdown of civilisation or the overpowering influence of a patriarchal state. Its scope isn’t that large.

Instead, the patriarchal state is reduced to the machinations of Positron. The Positron Project has been made possible due to the desperation caused by the financial crisis. Positron offers safety, food and full employment for those accepted behind its locked walls. Positron has been established around a prison. As part of its social solution, applicants must submit themselves to one month of imprisonment out of every two. During the other month, they will be given a home and employment. During their month in prison they are given alternative duties and are treated well. After all, their wardens know that the people they guard this month may be guarding them the next. This arrangement, it turns out, is essential for the working of the community and its economic viability.

Naturally, Positron must make money to provide. Among the industries being run behind the locked gates is an experimental business in sex robots. But that’s not all. But there are more sinister overtones, too. What’s been happening to the original prisoners; those who the project inherited, not selected? There’s more to this community than meets the eye. Once inside, no-one is allowed to leave.

This may seem to sum up the story, but it’s really only a prelude to the real story of sexual misconduct, sexual abuse and repression. In fact, the scenario Atwood presents of a medical procedure that will force its recipient to imprint on the first person (or object with eyes) they see – is potentially more horrifying than the fate endured by women in The Handmaid’s Tale. Yet, strangely, this is a lighter story. Why?

This brings me back to that question about the literary underpinnings of the novel. Ed, the head of Positron, is its Pygmalion character, willing to manufacture women robots for the sex trade for his own financial and sexual gratification. His intention to also create a line of Elvis and Marilyn sex-bots for the fetishistic pleasure of the wider community perhaps even says something about the Pygmalion-drive of fandom itself. All this is rather silly, and Stan’s involvement with the Elvis entertainers and green men, or Veronica’s sexual perversion for a blue teddy bear – it’s the first thing with eyes the poor woman saw after her medical procedure – suggests Atwood wants us to take this lightly, even if there is something sinister behind the scenario.

Part of this lightness lies with the structure of the novel, which broadly follows that of A Midsummer Night’s Dream. In that play Lysander and Helena escape into the Athenian woods at night after Helena has been sentenced to death by her father, Egeus, for refusing to marry Demetrius. The lovers are waylaid by fairies in the forest who use a magic potion which at first causes confusion, but is eventually used to right all wrongs. Demetrius is made to stay in love with Helena instead, and the play ends with a marriage and celebration. The play progresses from what is potentially tragic to a comedic end.

This is where the dystopian potential of this novel is not fully realised. The dark potential for violence at the beginning of the novel is lost, made irrelevant like Egeus’s exception to his daughter’s marriage. Positron, like the forest outside Athens, offers the opportunity for plot twists and sexual confusions that become comic, with a denouement every bit as magical and propitious as that offered by Shakespeare. Atwood isn’t concerned with the social breakdown at the beginning of the novel, which increasingly seems, as the novel progresses, to have been a plot device. There is a sense that the serious points that Atwood makes about sexual exploitation and personal liberty are somewhat trivialised. I felt that the use of Shakespeare’s play as a structural template contributed to this.

This is an argument that might raise objections, since the implications of sexual exploitation of women here is, as I have said, potentially worse in some instances than that of The Handmaid’s Tale. Yet the exploitation is also as much a part of the denouement as the magic flower from Shakespeare’s play, used both to cause trouble and to solve it. There is a sense that having walked you to the edge of the cliff and shown Hell in that dark chasm, Atwood has offered a fun ride across the expanse on a flying fox, instead.

For all this, this is a book I enjoyed, even if I found the ending somewhat disappointing. I enjoyed the sexual hijinks and confusions, the readerly joy of turning the page and wondering “what’s next?”, and the fun of the story as well as the mortifying potentials it offered. The thought of Ed, the book’s Pygmalion, injured with his penis stuck inside a malfunctioning sex robot, was actually funny. There’s a lot of stuff like that. Actually, this was a pretty strange book.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed Facebook

Facebook Instagram

Instagram YouTube

YouTube Subscribe to our Newsletter

Subscribe to our Newsletter

No one has commented yet. Be the first!