Those familiar with Geoffrey Chaucer’s Canterbury Tales will realise immediately, merely from the title, that Karen Brooks’s latest novel, The Good Wife of Bath, has a connection with Chaucer’s character, the Wife of Bath. In fact, Brooks’s novel, as historical fiction, is a feminist retelling of the prologue to the Wife of Bath’s Tale, drawing also upon the tale told by the wife, Alyson. If you are considering reading this novel I would strongly recommend – although it is not absolutely necessary – that you familiarise yourself with Chaucer’s original prologue and tale. Chaucer wrote in an earlier version of English, now called Middle-English, without standardised spelling, so some people will find him a difficult read. If that’s the case, I recommend a modern translation by Neville Coghill, particularly because it is the version used by Brooks in her novel. Read in translation, the Wife of Bath’s prologue and her tale are very quick reads. It’s worth this small effort, as I hope this review will show. Because Brooks’s novel is witty, funny, dramatic and really well told. With Brooks’s character, we can imagine how the Wife of Bath might have told her own story.

Brooks’s Wife (for reasons that become plain when you read the novel) is called Eleanor, not Alyson. This review will contain no spoilers, so I won’t go into why Brooks has done this. In The Good Wife of Bath Alyson is, instead, Eleanor’s closest friend. Initially, however, their relationship is acrimonious. Alyson is the step-daughter of Eleanor’s first husband, Fulk Bigod, sixty one years old, who she is forced to marry when she is only twelve. This was young but not illegal in the Middle Ages. Ironically, Alyson is six years older than Eleanor, who has now become her step mother through marriage. Eleanor has been forced into this marriage after Father Layamon is caught trying to ‘swyve’ her. While he did not succeed and he was the adult, it is Eleanor, as a girl, typical enough for these times, who finds her reputation at risk.

‘Swyve’ is a Middle English word and its context in the story makes it easy to understand that it means to have sex. Brooks peppers her novel with Middle English words with readily apparent meanings, although there is also a short glossary at the end of the book. Of most importance is Alyson’s use of the Middle English terms ‘quoniam’ and ‘queynte’. In the case of the latter, which she uses most often, Brooks is using the word as a literal translation of ‘cunt’: “he pressed his face into my tunic, his breath hot against my queynte, which was, I confess, becoming rapidly heated as well.” However, the word did not necessarily have this literal meaning in Middle English, but rather suggested something pleasing, elegant, curious or even ornamental. Our word ‘quaint’ may be derived from ‘queynte’, or the two words may have been used as puns in the Middle Ages. This usage was common enough that Renaissance writer Andrew Marvell could repeat the pun in his poem, ‘To His Coy Mistress’: “then worms shall try / That long preserved virginity, / And your quaint honour turn to dust, / And into ashes all my lust.” Chaucer’s use of the word – his intention just as readily understandable by its context – is therefore somewhat euphemistic. The fact that Brooks also inserts the more modern form ‘cunt’ into the text occasionally, but over the course of two specific pages uses both forms – ‘queynte’ and ‘cunt’ – is slightly strange, but it shows us that Eleanor understands her own sexuality and owns the term in all its gynaecological reality. Eleanor is a woman with whom women in the twenty-first century might sympathise. She desires independence and she is openly, unashamedly desirous of sexual gratification.

Of course, such an open admission in the Middle Ages was not possible for a woman who also desired social acceptance. When the young Eleanor finally consummates her marriage with Fulk Bigod, she reflects, “It was a duty, another expectation placed upon us by God and man.” This is in stark contrast to the Eleanor who eventually marries her fifth husband, Jankin, at the age of thirty three. In fact, it is at her fourth husband’s funeral that she first notices Jankin’s alluring qualities and is overcome by lust:

My eyes travelled, noticing anew how broad his chest, how chiselled his legs. How he bulged in his hose in a way that made my insides molten. Though I’d appreciated so many of his qualities before, only now, before my dead husband, did I appreciate the bits that made him so very, very manly. I swallowed.

The Good Wife of Bath, page 289

This older Eleanor has more in common with the Wife, Alyson, of Chaucer’s poem. Of her five marriages, the Wife says:

- Yblessed be God that I have wedded five!

- Welcome the sixthe, whan that evere he shal.

- For sothe, I wol nat kepe me chaast in al.

- Whan myn housbonde is fro the world ygon,

- Som Christen man shal wedde me anon,

- For thane, th’apostle seith that I am free

- To wedde, a Goddes half, where it liketh me.

‘The Wife of Bath’s Prologue, lines 44-50

- Blessed by God that I have wedded five!

- Welcome the sixth, whenever he appears.

- I can’t keep continent for years and years.

- No sooner than one husband’s dead and gone

- Some other Christian man shall take me on,

- For then, so says the Apostle, I am free

- To wed, o’ God’s name, where it pleases me.

On sexual matters, the Wife is direct and unblushing, suggesting that genitals were made for pleasure:

- Why sholde men ells in hir books sette

- That man shal yelde to his wyf hire dette?

- Now wherewith sholde he make his paiement,

- If he ne used his sely instrument?

- Thanne were they maad upon a creature

- To purge urine, and eek for engendrure.

‘The Wife of Bath’s Prologue, lines 129 - 134

- Why else the proverb written down and set

- In books: “A man must yield his wife her debt”?

- What means of paying her can he invent

- Unless he uses his silly instrument?

- It follows they were fashioned at creation

- Both to purge urine and for propagation.

The thinking embraced by the Wife feels modern: the idea of female independence and sexual emancipation. When she paraphrases arguments first put into the mouth of the Wife of Bath by Chaucer in the fourteenth century, she nevertheless feels contemporary. Here are three statements by Brooks’s Eleanor followed by Chaucer’s Alyson for comparison:

“There’s no finite number of husbands for women, nor wives for men, so why not multiply them?”

- No word of what the number was to be,

- Then why not marry two or even eight?

- And why speak evil of the married state?

“One in bed, the other in my heart and head”

- No sooner than one husband’s dead and gone

- Some other Christian man shall take me on

“If seed is never sown, then how can fresh virgins be grown?”

- And certainly if seed were never sown,

- How ever could virginity be grown?

The fact that Brooks, as a modern writer, draws upon Chaucer’s text, may suggest that she merely gives these values a new audience. But it is not as simple as that. Rather, the two texts, read together, create an interesting juxtaposition beyond mere entertainment. Brooks’s novel is in dialogue with Chaucer’s poem, weighing desires for revenge and dominance against the possibility for true reform and equality.

Imagine that from the start that The Good Wife of Bath, and Chaucer’s prologue and tale of the Wife of Bath had been written with the intention they be read together: perhaps, even, that Brooks’s novel – and presumably the life of Eleanor and her relationship with Chaucer – came first; that when Chaucer wrote ‘The Wife of Bath’s Tale’ he really did base his character on Brooks’s Eleanor, with the full knowledge his own self, as characterised in this modern retelling, possesses. This is the metatextual premise that Brooks’s story encourages. Of course, being a novel, Brooks has necessarily a lot more detail to flesh out. But her story also includes events that don’t appear in Chaucer’s poem which fundamentally change the story. In fact, about two thirds of the way through, the story changes entirely, propelling it beyond the ending suggested by Chaucer’s Alyson. In Brooks’s telling of it, Chaucer knows these later events, too, even when he comes to appropriate Eleanor’s story for his own ends. As readers, we begin to imagine gaps in Chaucer’s original: elisions; details – incriminating details – that have been left out. These ‘elisions’ offer a new perspective on Chaucer’s tale, highlighting, for a start, that the Wife’s representation is made by a man, with all the problematic questions that that raises. The novel thereby interrogates assumptions of Chaucer’s time that may, or may not be, promoted within the text. In her author’s note at the end of the book, Brooks explicitly asks questions implied by her story:

. . . was she [Alyson] simply a ventriloquist’s dummy? Or was Chaucer giving the women of his time a platform, offering something more than what folk of the Middle Ages expected from the female sex? Was he being ironic? Was it satire? And if so, who was he satirising? Men? Women? Marriage? All of the above?

The Good Wife of Bath, Author's Note, page 533

Brooks’s Chaucer is a good friend of Eleanor, and despite his rise in society and her lowly status, he maintains their friendship for decades, even when Eleanor is angered by him and refuses to see him. Brook’s Chaucer is sympathetic and supportive of Eleanor’s position over her multiple husbands. Nevertheless, he is also instrumental in arranging Eleanor’s first marriage to Fulk Bigod when her reputation is at stake. The complexities of Brooks’s representation of Chaucer allow her to examine Chaucer’s work from Eleanor’s point of view and offer a means for modern readers to reconcile their values with some of the more problematic aspects of Chaucer’s text.

First, is Chaucer’s representation of the Wife, herself. The Wife, as an advocate for female independence, is not an entirely a laudable character. Apart from the stances she takes, which would have been challenging in the fourteenth century – open sexuality, her learned responses to patriarchal values and their supporting texts, and her insistence that she has as much right to remarry as a man – she proves herself to be manipulative. And far from seeking equality, she wants to dominate her husbands in the manner that she desires, herself, to avoid. She withholds sex, uses false and aggressive accusations to control her husbands, and feigns infidelity to make her third husband jealous, all to achieve dominance. Her talent lies also in turning texts of male authority against patriarchal power. For instance, by twisting the story of Job and his patience, she can tell her third husband:

- Oon of us two moste bowen, doutelees;

- And sith a man is moore reasonable

- Than woman is, ye moste been suffrable.

‘The Wife of Bath’s Prologue, lines 440 - 442

- One of us must be master, man or wife,

- And since a man’s more reasonable, he

- Should be the patient one, you must agree.

In truth, Brooks’s Eleanor has the same characteristics. She uses sexual jealousy to manipulate her third husband and accuses him of murder, whether true or not, to gain control of his business, which he runs poorly. It is Alyson who acts as her moral compass: “This marriage,” Alyson tells Eleanor, “this set you have against your husband, your desire to quash him and emerge the victor, it’s changed you, Eleanor.” While Eleanor is similar to Chaucer’s wife, she is also more complex because she begins to desire a more principled path in her quest for self-determination, rather than be debased by it. She wants something better than merely to turn the tables.

The idea of turning the tables may find sympathy with many modern readers. Indeed, the Wife’s intelligence is admirable and an argument that her social position as a woman in fourteenth century society requires her to act in underhanded ways to subvert patriarchal power also has merit. But this is not the point Brooks is making. When Eleanor discovers that her own story has been appropriated by Chaucer and that she has been caricatured in this way, she is furious. She won’t talk to Chaucer. Far from wishing to dominate men, Eleanor rather desires autonomy: to live free of the restrictions and impediments placed against her for being a woman; that make it so hard to earn a living from a trade in which she has proved adept: wool spinning and weaving:

I wanted authority, aye, but not over my husbands. That made me no better than them. What I really wanted, what I’d learned through experience, was authority over myself. I wanted respect.

The Good Wife of Bath, page 453

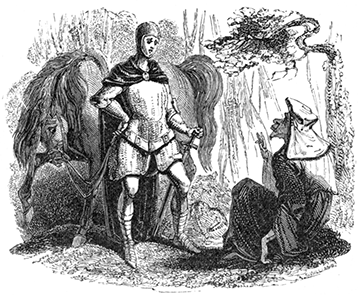

This is where reading the two texts together becomes interesting. But first, to continue this point, it is useful to consider Chaucer’s version some more. Beyond the prologue, which is what Brooks’s novel mostly draws upon for its own plot, is the tale told by the Wife of Bath. Her tale is about a Knight who rapes a young girl. He is sentenced to death by King Arthur. But the queen intervenes to save him. She sends him on a quest to find out what women want most, and he has a year and a day before he must return to court with an answer to save his life. The knight is given all manner of answers as he travels: that women want wealth, pleasure, nice clothes etcetera. Finally, just before he must return in failure, the knight meets an old, ugly woman. She promises the knight she will tell him what he needs to know as long as he agrees to do what she asks of him. The answer the old woman gives him is much as we might expect from the Wife who is telling the story:

- Wommen desiren to have sovereynetee

- As wel over hir housbond as hir love,

- And for to been in maistrie hym above.

‘The Wife of Bath’s Prologue, lines 1038 - 1040

- ‘A woman wants the self-same sovereignty

- Over her husband as over her lover,

- And master him . . .

However, this is not all there is. This is not where the tale ends. Because the Wife’s story is a retelling of a popular tale from the Middle Ages, of Sir Gawain’s marriage to Lady Ragnelle, another version of the common literary trope of the ‘loathly lady’. In most versions, an ugly old woman appears at a moment when her help is needed. She agrees to help once she is promised that she will be married, or a promise is made that will lead to this demand, as happens in the Wife’s tale. Chaucer’s Wife of Bath emphasises the ugliness of the old woman, especially through the knight’s pleas to be released from his obligation to sleep with her once he is forced to marry her. A description of this character trope is more graphic in the story of ‘Peredur Son of Evrawg’ in The Mabinogian:

She held rough thongs for beating the mule, and she had a rough, unlovable appearance: her face and hands were blacker than pitch, and yet it was her shape rather than her colour that was the ugliest – high cheeks and a sagging face, a snub, wide-nostrilled nose, one eye speckled grey and protruding, the other jet black and sunken, long teeth yellow as broom, a stomach that swelled up over her breasts and above her chin. Her backbone was shaped like a crutch; her hips were wide in the bone, but her legs were narrow, except for her knobbly knees and feet.

‘Peredur Son of Evrawg’, The Mabinogian, (trans. Jeffrey Gantz), Penguin Books , 1976, page 248

But the loathly lady is magical. She has the ability to change her appearance. In Chaucer’s version, she gives the knight a choice: he can either have her as a young, beautiful wife whose fidelity cannot be trusted, or ugly as she appears, but wholly faithful. It is the knight’s decision that provides the true denouement to the Wife’s story: he allows the old woman to make the choice herself. Given a choice, the loathly lady chooses to be both young and beautiful, as well as faithful. This is the solution that suggests the happiness that choice and equality allows. It contrasts to the ending of the prologue, in which the Wife shames her fifth husband, Jankin, into submission, after he hits her for tearing his book, full of misogynistic stories. The Wife hits him back, and he submits with words that may ring hollow for modern audiences: “So help me God, I never again will hit you, love.” (“Fool that I was, I believed him,” remarks Brooks’s Eleanor in the same situation). Nevertheless, as a show of his submission, Jankin cedes his property and its management to Alyson. The contrast is clear: the Wife gains autonomy through the same violence practised by her husband, while the knight, who begins his journey by raping a girl, ends it by willingly giving his wife a choice. This is the difference between Chaucer’s wife and Brooks’s Eleanor, too.

Eleanor’s marriage to five men allows a broad enough scope in the narrative for Brooks to explore this notion of what women truly need and want from their lives. None of Eleanor’s marriages are ideal. Her first three husbands are much older than her and all die from sickness and age. Her second husband marries her only for her property, while her third husband, though kind and enlightened – he has seen her talent and wants her to manage his business – is homosexual and therefore unable to offer Eleanor the physical gratification she craves. Her fourth husband is a philanderer, as suggested by Chaucer’s tale, while her fifth, Jankin, a scholar who has helped Eleanor learn to read, is also a misogynist with a quick temper and violent inclinations. Yet in retelling Alyson’s story, Brooks is exploring similar possibilities: of equity in marriage, as well as expressing the desire in the latter part of the novel that women may be autonomous and make choices in their own lives.

In exploring these possibilities Brooks subtly offers a reversal of the loathly lady paradigm in Eleanor’s first marriage, since Brook’s intends not just to paraphrase Chaucer but to question the impulse to dominate. Fulk Bigod has little to recommend him. He is an old, dirty looking man who smells. His reputation around the town is akin to a fourteenth century Boo Radley:

He’d been on the edge of the Green when we first danced around the maypole and played games on May Day morning. We’d nudge each other, laughing and nodding towards him, the man with no friends, knowing his mission to find servants, another wife, would fail. Ever since his last wife died a few years ago, the story was he’d been desperate to remarry. But the villagers kept their daughters away and refused his increasing offers in exchange for another bride.

The Good Wife of Bath, page 19

Fulk Bigod is rumoured to have murdered his first wife. There are a lot of unkind rumours about him. He is an outcast. But Eleanor, disgraced by her liaison with Father Layamon, has no choice but to wed him. The circumstances are not great for her. And yet, things turn out to be not so bad. Like the loathly lady, Fulk Bigod is initially represented by exteriors. His house, for instance, has the shit of the farm animals everywhere, the thatch on the roof needs repair, the doorframes and window frames are splintered and the place is choked by weeds and vines. Inside, the furnishings are old, the crockery chipped and the fireplace smokes, causing noisome fumes. But as in the story of the loathly lady, Fulk Bigod changes in Eleanor’s eyes. As she gets to know him, as she helps tidy his house, as she speaks to Chaucer about him and learns his real story, he is transformed. But instead of the loathly lady, Fulk Bigod is likened to Cupid to Eleanor’s Psyche, instead. In Greek legend Psyche marries a monster in order to protect her city. Asked never to look upon him, Psyche one night holds a lantern to her husband and discovers that he is, in reality, the beautiful Cupid, not a monster. This is Fulk Bigod, a man of noble intentions and actions, who is kind and enlightened enough to trust in Eleanor’s intelligence and her capacity to run his farm. It’s important to the story because Brooks suggests through this first marriage, whatever follows, that harmony, respect and trust between the sexes is possible.

It is this interrogation of Chaucer’s original intention that makes The Good Wife of Bath a modern and humane story. With a believable historical backdrop covering the reigns of Edward III and Richard II, with appearances by historical personages such as John of Gaunt, friend and patron of Chaucer, Isabella of France and John Wycliffe, responsible for an early translation of the Bible into English, as well as a chief adherent of Lollardism. The Lollards questioned the authority of the Pope and restrictions placed upon women, and their cause is mentioned in whispers. Brooks cheekily subtitles her novel “A (mostly) true story”, and you will find that glimpses into the political, religious and social life of the fourteenth century is fairly faithful to the novel’s historical basis. And the novel also follows the story Chaucer lays out fairly faithfully too. But there is so much more to the novel than a retelling: all the things this review avoids mentioning in order to avoid spoilers, for a start. And all those things Chaucer presumably omitted when he wrote his prologue and tale based on the life of Eleanor, presumably, if you want to play along with the premise of this book. It’s called The Good Wife of Bath because Eleanor wants not to be ‘moral’ in a patriarchal sense, but to reject patriarchal judgment and be honest, decent and honourable on terms that are fair, humanistic and decidedly modern. I was hoping for a good story when I started this book, and I got that. But The Good Wife of Bath is learned and topical too, despite its medieval setting. Go out and find a translation of Chaucer by Coghill, read it, then read this!

The Canterbury Pilgrims - North Reading Room, Library of Congress

The two images below depict the pilgrims on their way to Canterbury to visit the shrine of St Thomas Becket. An aspect of the novel this review does not cover is the humorous representation of the pilgrims as modern-style tourists, buying holy relics at the gift shop. Eleanor embarks on several pilgrimmages throughout this novel, usually during a time of crisis. The pilgrims appearing in Ezra Winter's murals, below, represent Chaucer's pilgrims and are labelled beneath each image:

Highsmith, Carol M, photographer. North Reading Room, west wall. Mural by Ezra Winter illustrating the characters in the Canterbury Tales by Geoffrey Chaucer. Library of Congress John Adams Building, Washington, D.C. , 2007. Photograph. https://www.loc.gov/item/2007687162/.

LEFT TO RIGHT: The Miller, in the lead, piping the band out of Southwark; the Host of Tabard Inn; the Knight, followed by his son, the young Squire, on a white palfrey; a Yeoman; the Doctor of Physic; Chaucer, riding with his back to the observer, as he talks to the Lawyer; the Clerk of Oxenford, reading his beloved classics; the Manciple; the Sailor; the Prioress; the Nun; and three priests.

Library of Congress, North Reading Room, east wall. Detail of mural by Ezra Winter illustrating the characters in the Canterbury Tales by Geoffrey Chaucer

LEFT TO RIGHT: The Merchant, with his Flemish beaver hat and forked beard; the Friar; the Monk; the Franklin; the Wife of Bath; the Parson and his brother the Ploughman, riding side by side

Another Related Book

RSS Feed

RSS Feed Facebook

Facebook Instagram

Instagram YouTube

YouTube Subscribe to our Newsletter

Subscribe to our Newsletter

No one has commented yet. Be the first!