We have no reviews for the Harry Potter novels on this website and we’re not likely to – I read them years ago – unless someone else wants to contribute some. But with Donna Tartt’s The Goldfinch we might have the next best thing for fans of the be-speckled one. I’m sure that in years to come someone is going to write a thesis about the influence of the Potter series on Tartt: they may claim that it is essentially fan fiction; further still, they may argue it is an extension of the Potterverse. If that seems far-fetched, I would point out that I never saw the link between the Twilight Series and 50 Shades of Grey (I admit I have read neither), but apparently there is one. The Goldfinch is like the book Potter fans might seek as they grow into adulthood.

So, let’s start with a rather whimsical comparison before I move on to more important things, like what the book is about and what I thought of it. First, Tartt’s Theodore Decker wears glasses! What’s more, another character, his friend Boris, calls him ‘Potter’ because of his resemblance to Harry Potter. Also, Theo loses both his parents in violent circumstances and is first sent to live with the Barbours, but eventually is taken in by a Dumbledore-like Hobie, a furniture restorer who spouts wisdom. When Theo’s dead mother appears to him, he can only see her in a mirror, just as Harry can only see his dead parents in the Mirror of Erised. Theo has to face forces who threaten to destroy Hobie, and is eventually drawn into a battle to save his world. What’s more, objects are imbued with the sense of their history and contain a ‘soul’, like a residue of the lives with which they have come into contact. In Harry Potter, Voldemort distributes his soul among seven horcruxes. And just as the Potterverse draws from various historical periods to achieve the aesthetic of its magical world, The Goldfinch achieves an aesthetic typical of dark academia, of an older period existing in the present, notable in Hobie’s restoration workshop, through the novel’s focus on Renaissance art and Theo’s interest in literature, like Dostoyevsky’s The Idiot.

There is no denying that there are echoes of J.K.Rowling’s novels in Tartt’s epic. (In fact, when I got this far into writing this review, I decided to Google it. Sure enough, others have also made similar connections.) Yet The Goldfinch is also a standalone novel, long, and rich in the detail one might expect from a nineteenth-century novel that tells an involving story.

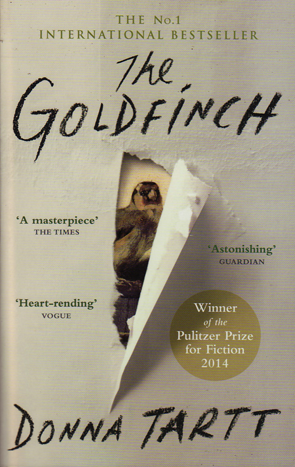

Theodore Decker has been suspended from school and is required to attend an interview with his mother and the school Principal. However, on their way to the interview it begins to rain, and since they are early, they take refuge in an art museum where Theo’s mother draws his attention to great works like Rembrandt’s ‘The Anatomy Lesson’ and Fabritius’ ‘The Goldfinch’. Theo’s attention is also drawn by a pretty red-headed girl in the company of an older man, and while his mother takes an opportunity to return to Rembrandt’s painting, Theo decides to try to talk to Pippa. It is in that moment of separation that a terrorist attack rocks the gallery. An explosion kills his mother. Dazed, Theo stumbles upon Welty, the man formerly attending Pippa, who gives him a ring and asks him to take it with a message to his business partner, Hobie. He also begs Theo to take Fabritius’ ‘The Goldfinch’ to protect it from men who have been looting the gallery in the confusion. This is the catalyst for a chain of events which are to define Theo’s life.

Theodore Decker is a far grittier character than Potter. He falls into depressions, becomes drug dependant and is not beyond theft or fraud. When he meets Boris as a boy in Las Vegas, they shoplift, smoke, sniff glue and experiment with drugs. As Theo grows older and becomes Hobie’s business partner, he defrauds customers by representing reproduction furniture as originals in an attempt to save the business. And Theo never returns the painting, despite having taken it at Welty’s request to save it from theft. He wraps it in newspaper to hide it and eventually hires a storage facility for it. He thinks he has things under control, but he soon realises that others have designs upon the painting, also, and he hasn’t covered his tracks as well as he might have hoped.

The Goldfinch has all the style and detail of a nineteenth century novel. The movie, adapted by John Crowley, plays with the narrative sequence to balance the past narrative of Theo’s childhood and his present dilemmas, as well as to place greater emotional emphasis on Theo’s relationship with his mother. The novel, apart from the opening chapter, is almost entirely linear, offering the reader the chance to become immersed in Theo’s world. With little foreshadowing, we are as uncertain as Theo about what might happen. Despite Theo’s failings, it is easy to understand the pressure of his limited choices and the horrors he has faced. Faced with the uncertainties about his fate should the painting be discovered in his possession, and exploited by a father caught in his own world of trouble, Theo is a vulnerable character who demands the reader’s sympathy.

So, the The Goldfinch attempts to offer a more complex moral universe than Rowling’s novels. The simple question of whether good may come of bad actions, and the opposite, is pertinent to Theo’s relationship with the painting. The truth of Theo’s initial impulse – that he might save the painting – is distorted by his failure to return it and the desires of others to own it. Is it possible that his situation, no matter how dark, might result in good?

But Tartt’s exploration of the notion of moral relativism becomes increasingly problematic throughout the novel. This is largely due to her effort to link the painting and other objects – old furniture or Theo’s mother’s earrings, for instance – with a concept of soul and morality. It is not enough for Tartt to juxtapose the fleeting lives of humanity with the more permanent works of art that are expressions of their creators. Instead, objects are imbued with a soul by their long histories and the lives that are worn upon them. Real antique furniture, Theo is taught, is worn asymmetrically, bearing the marks of its history that give it its soul. Reproduction furniture lacks this, and Hobie’s ‘changelings’ – old furniture he has cobbled together from the remains of other pieces along with the new – are curiosities at best, and at worst, soulless Frankenstein creations.

Instead of offering us a trite assertion that the past must be preserved, Theo instead meditates upon the notion of ‘beauty’ itself: a transcendent link to a numinous world; an insight into the soul of those enlivened by their connection to beautiful objects and their preservation. Beauty – through the agency of art – is an ‘other’ that is at once separate to the self, but potentially working upon the grain of the soul, to use a metaphor worthy of Hobie’s workshop. Hobie tells Theo, beauty alters the grain of reality.

This notion of ‘beauty’ is not dissimilar to Keats’s in ‘Ode to a Grecian Urn’ – Beauty is truth, truth beauty,—that is all / Ye know on earth, and all ye need to know.

– and the novel is thematically similar to the poem: human existence is fleeting but art offers truth and beauty which transcend our lives and is potentially timeless. Before the explosion in the museum, Theo’s mother speaks to him of the loss of much of Fabritius’ work in an explosion four centuries earlier:

People die, sure [. . .] But it’s so heartbreaking and unnecessary how we lose things. From pure carelessness. Fires, wars. The Parthenon, used as a munitions storehouse. I guess that anything we manage to save from history is a miracle.

It is possible to be unnerved by this ambivalence to human life and suffering; it is somewhat cold and esoteric. Beautiful things – art, architecture – represent a collective human soul but the individual life is short and pointless:

For humans – trapped in biology – there was no mercy: we lived a while, we fussed around for a bit and died, we rotted in the ground like garbage. […] But to destroy, or lose, a deathless thing – to break bonds stronger than the temporal – was a metaphysical uncoupling all its own, a startling new flavour of despair.

By setting the transcendent as ‘other’ to humanity, Tartt’s narrative attempts to walk a line between modern secular despair and nihilistic denial of purpose, and a desire for transcendent truth which has supplanted traditional religious impulses with notions of purpose and self, drawn from Romanticism. Yet the novel fails to reconcile human despair to beauty. Purpose and morality remain other.

Theo, himself, is driven to the depths of self-destruction and nihilistic thought as he struggles with the horrors and pressures of his life. He sees the apocalypse of death in his everyday world. Recalling the nature mortes his mother showed him in the museum, Theo sees the human condition in nihilistic terms as one of putrefaction:

The writhing loathsomeness of the biological order. Old age, sickness, death. No escape for anyone. Even the beautiful ones were like soft fruit about to spoil.

Theo is filled with despair; his life spins out of control and there seems no hope for him. In fact, this is a rather dark novel steeped in the realities of crime, drugs and personal tragedy. Yet Tartt’s denouement elides these realities in favour of the rather more esoteric meditation on the meaning of beauty and the soul, and the problem of understanding morality through limited human perspectives. While the novel eschews any absolutist morality, it relies upon similar morel tenets as that of some religions, in that moral authority resides outside the self rather than within. Hobie’s assertion the line of beauty is the line of beauty

represents another kind of outward looking faith that merely replicates the circular logic of Exodus: I am what I am

.

In the end, my impression of this book is that it is an immersive story with a sympathetic character and engaging plot. Yet the resolution seems contrived and unsatisfying because Tartt cannot attribute moral agency to her characters. And because of that it’s hard to see the point of Theo’s journey, despite his large claim that he has had his own Damascus

, another religious allusion to the conversion of St Paul. Theo lives in the real world of drugs and crime, but the reader is expected to accept an aesthetic doctrine as the panacea to Theo’s problems and modernity’s ills.

Fabritius’s painting remains determinably at the centre of the story, a thing like the furniture that Hobie works with, accreting character and history, but remains removed from the lives which it affects. Theo describes the greatness of the painting as Transubstantiation where paint is paint and yet also feather and bone

: that the greatness of the painting is that it can at once exist in the imagination and also deconstruct its own pretension to reality. I think Tartt has attempted something similar with her novel. Unlike the bird and the painting however, Theo remains separate to the moral agency of art and beauty. The failure lies, I think, in that Tartt cannot logically reconcile Theo’s moral quagmire with her thesis, and is forced to rely upon a more nebulous explanation: magic. Art becomes The magic point where every idea and its opposite are equally true

. But this is moral relativism twisted out of shape. The best and worst of what we can be is relative to the outcome or the situation or what have you, and personal choice and agency become irrelevant: We don’t get to choose the people we are.

Tartt seems unable or unwilling to reconcile those extremes, leaving Theo’s moral redemption not his own. I suspect part of what people found disappointing in the movie was the unsatisfying conclusion that this thinking imposes on the story. It was more difficult to conceal in the movie. But the problem existed first in the novel. I was left wondering whether Tartt had, in the end, abandoned true character development for aesthetic principles, and whether that was enough for such a long story that draws upon the ‘hero’s journey’ structure and, of course, Harry Potter.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed Facebook

Facebook Instagram

Instagram YouTube

YouTube Subscribe to our Newsletter

Subscribe to our Newsletter

No one has commented yet. Be the first!