The Fraud is Zadie Smith’s first historical novel. Sometimes it is difficult when finishing a book like The Fraud to immediately identify if the seemingly disparate elements of the story’s construction are cohesive. We expect each element of a novel to serve a purpose even if this is not how real life works: that if anything is to be introduced into the story it serves the progression of plot, characterisation or ideas, like Chekov’s gun, which should never appear unless it will later be fired.

If there is a criticism to be made of The Fraud, it instinctively rests on this feeling: that the novel has many seemingly disparate parts that are difficult to reconcile. Towards the end of the novel some chapters do not flow as smoothly as they should. Smith is attempting a lot. She is trying to write about a famous court trial, dramatize the life of a now-obscure writer and his coterie of writing friends, follow the moral and intellectual growth of her protagonist, Eliza Touchet, suggest the complexities of Eliza’s position in her cousin William Ainsworth’s household, as former lover both to him and his wife, address the problem of class in Britain and the exploitation and immoralities of the slave trade, tell the history of the Tichborne family in Jamaica and their role in the exploitation of slaves, as well as touch upon nascent revolutionary movements within England. It’s a lot to cover, even with a novel of this length. Smith herself has written, “When I tried to explain to anyone what all these subjects had in common, I did not sound like a person writing a historical novel as much as a person who had entirely lost the plot.”

I might even say that Smith’s characterisations are not always of an even quality. Some characters feel like avatars for a particular stance. Charles Dickens, that most famous of nineteenth century novelists, appears frequently in the story, much to Smith’s chagrin, it seems (see her article Zadie Smith, ‘On Killing Charles Dickens ’, The New Yorker, 3 July 2023), but there is little of that well-loved author here: he feels like a facet of a personality; a controlling workaholic with little time for friends; merely a moralist whose wealth has placed his views beyond the sentimental working class of own characters. Henry Bogle, the son of a Jamaican slave, Andrew Bogle, is merely an angry young man with a soap box, even if you like his soap box. But Smith knows how to create complex characters, too. Eliza Touchet inhabits a complex moral and emotional universe. She is a respectable widow running her cousin’s household while he writes his novels, as well as his former lover: and former secret lover to his now dead wife, Frances, as well. Eliza will take up the cause of Abolition and struggle with moral precepts she cannot, herself, escape. We are encouraged to believe that Eliza’s intellectual and moral journey makes her most closely aligned with Smith’s. She secretly writes a novel that bears the same title as Smith’s own book. Even a minor character like Sarah Wells, second wife to William Ainsworth, is drawn more completely than we may initially expect. She may be from low stock (her parents professions being “’Boot-black’ and ‘Prostitute’”), and she may seem unsophisticated in her willingness to believe the claims made by the Tichborne Claimant, but she shows herself to be a steely, worldly woman who understands her position. When she takes Eliza into the poorest parts of London, she not only shows self-awareness, but an independent and imperturbable strength.

The narrative thread rests on two main historical realities, a famous court trial held in the early 1870s and the story of William Ainsworth. William Ainsworth was a nineteenth century contemporary of Charles Dickens. He wrote thirty nine novels and took over the editorship of Bentley’s Magazine when Dickens gave it up. His big boast, which Smith allows him to make, is that his novel, Jack Sheppard, outsold Oliver Twist. Nevertheless, by the end of the century, Ainsworth’s novels were entirely out of print. Even Eliza, his first reader, is appalled by their quality and gives up attempting to edit them or make suggestions. To make the point, Smith even quotes passages of his prose. If they’re representative, he was terrible. But Ainsworth is a part of the Kensal Lodge set, a group of writers including Dickens and Thackeray, and artists like George Cruikshank, who meet and discuss their work. Eliza keeps house for Ainsworth, despite his having recently married Sarah Wells. Eliza’s own husband and son have died from scarlet fever and now Eliza wonders what she is for: she feels herself facing the ‘void’, that existential sense of purposelessness.

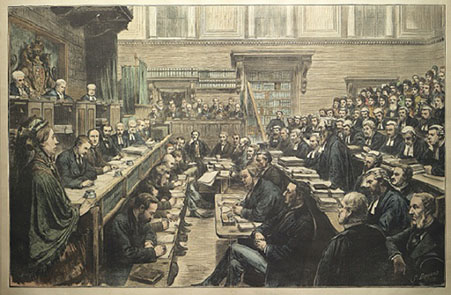

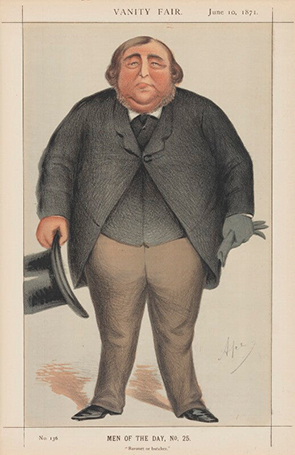

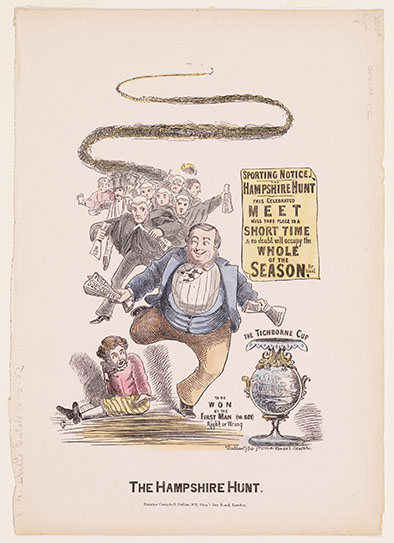

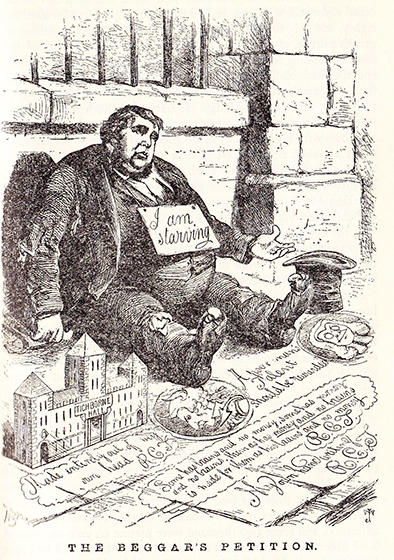

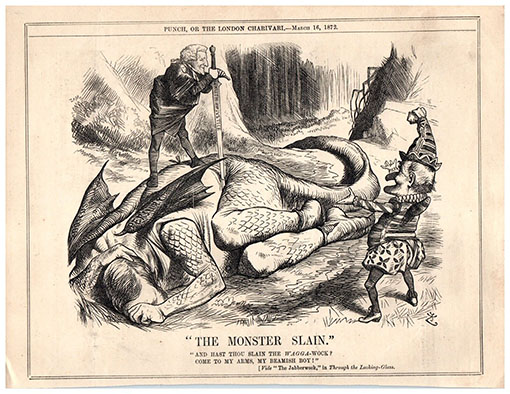

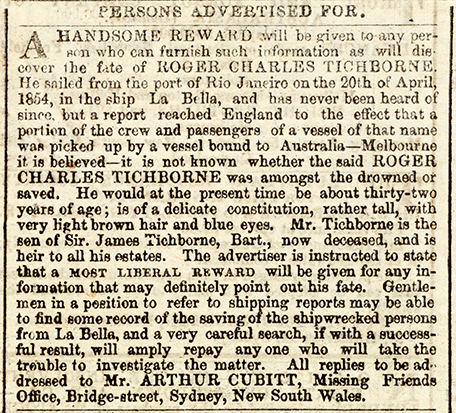

The second important historical context for the novel is the trial for perjury of the man known as ‘the Claimant’ to the public, who is eventually identified as Arthur Orton, also known as Thomas Castro in Australia. He claimed to be the heir to the Tichborne-Doughty estate: that he was Sir Roger Tichborne, thought to have died when his ship, the Bella, sank enroute to Jamaica in 1854 when Sir Roger was twenty-five. Sir Roger’s mother, Lady Henriette Tichborne, could not accept that her son was dead, so it was only natural when there was news that some members of the ship had been rescued and taken to Melbourne, Australia, she would try to find him. Lady Tichborne published a number of advertisements in Australian newspapers and eventually a man working as a butcher in Wagga Wagga (there known as Thomas Castro) claimed to be her son. He returned to England and despite his dubious claim, she accepted him. His claim was dubious because of a few elementary facts: he was overweight and continued to gain weight after his return to England, so if he was Sir Roger his physical appearance had changed dramatically. Also, Sir Roger had been a fluent French speaker – his first language – and even spoke English with a French accent. The Claimant knew no French and spoke with a distinctly British working class accent. Nevertheless, Lady Tichborne believed him and all was fine for ‘Sir Roger’ until she died in 1868. The rest of the family did not believe the Claimant. Even so, he sued Colonel Lushington, the current resident of Tichborne Park, to have him evicted, which, had he been successful, would have established his identity in law. However, the Claimant’s case failed after it was revealed he did not have tattoos that Sir Roger was known to have had. He was charged with perjury which precipitated the trial that features in this novel. News from the trial held wide appeal. It was closely followed, much like that of O.J. Simpson: it dominated the papers, it inspired cartoons, and eventually, stage plays and novels.

Alongside the story of the Claimant is the story of Andrew Bogle. Bogle’s father had been tricked into slavery and Bogle was born a slave. He worked for Edward Tichborne, Sir Roger’s uncle (later to be known as Edward Doughty due to the terms of an inheritance) on his Jamaican plantations, and knew Sir Roger when he was young. Bogle supports the Claimant. His testimony mesmerises Eliza. She instinctively feels he is an honest man even though she is sceptical of the Claimant, himself. During the trial prosecutors would accuse Bogle of feeding the Claimant personal information about Sir Roger in order to support his ruse. As a novelist, Smith refuses to untangle the contradictions.

This is a relativism in The Fraud that makes it a distinctly modern novel. The Claimant’s case may seem weak but the novel offers no definitive position on its merits. Smith has claimed, perhaps somewhat facetiously, that she left England for ten years because she did not wish to write a historical novel: “any writer who lives in England for any length of time will sooner or later find herself writing a historical novel, whether she wants to or not.” Smith felt historical fiction was nostalgic and “aesthetically and politically conservative”. However, The Fraud avoids the indulgence of nostalgia and is acutely relevant because it exceeds the bounds of its historical subject. With reference to the work of writers like Marguerite Yourcenar, Daniel Kehlmann and Hilary Mantel, Smith says she came to understand,

Not all historical fiction cosplays its era, and an exploration of the past need not be a slavish imitation of it. You can come at the past from an interrogative angle, or a sly remove, and some historical fiction will radically transform your perspective not just on the past but on the present. These ideas are of course obvious to long-term fans of historical fiction, but they were new to me.

Zadie Smith, ‘On Killing Charles Dickens ’, The New Yorker, 3 July 2023

Smith’s novel lives up to this insight: it is both a layered exploration of the world of the nineteenth century as well as achieving a kind of parodic equivalence with the world of modern America – of Trumpism if you’re willing to see it in the text – and our era of post-truth politics.

As modern readers we are both entertained by the story of the trial and the seemingly gullible followers of the Claimant, as well as the broad parallels with Trump’s specious claims and his followers’ devotion. Despite his weak case, the mounting evidence against the Claimant only proves his authenticity to the Claimant’s true believers: “. . . such dry and inconvenient facts were of no consequence here, in this ocean of feeling”. And despite his high social status – if his story is to be believed – the Claimant’s case becomes a cause célèbre for the working class. The Claimant’s working class manner makes him relatable, and he becomes a symbol of working class grievance against the system. This may seem a rather subtle parallel to our modern world for some, but at times Smith quite blatantly makes the connection between the Claimant’s case and Trumpism. She uses a poem, ‘The Faker’s New Toast’ as an epigraph to Volume Eight of her novel, which ends each stanza with a refrain “And a trump”, “Like a trump” and “Of a trump”. The poem was a canting song that imagined the reversal of class fortunes in Britain and held writers like William Ainsworth (who used Dick Turpin as a character in several of his novels, and is Eliza’s cousin and former lover) as a hero. Here, the word ‘trump’ is most likely used for its informal nineteenth century British meaning: ‘a fine or reliable person’ (Collins Dictionary). But the modern context is unavoidable. When followers of the trial who refuse to believe evidence or paradoxically feel it proves the opposite of what it suggests, their defiance has echoes of Trump’s supporters. The Claimant’s supporters hold up signs, one of which reads ‘Fools and Fanatics for Kenealy’ (Kenealy was the Claimant’s lawyer) recalling the badge of honour Trump supporters made of Hilary Clinton’s pejorative “deplorables”.

But this satirical touch is not all there is to the novel. Again, there is so much happening here, it is easy to be overwhelmed and believe the whole thing doesn’t quite work. But the structure of a novel can be like a complex origami piece: pull this piece and that piece together, or blow here, and what seems abstract takes shape. There is a moment early in the story when William Ainsworth returns from Europe after an absence of nine months. In that nine months Eliza has begun an intimate relationship with Frances, Ainsworth’s wife, and now she must repress those feelings. Eliza envies Ainsworth, not for the interesting places he has visited and sights he has seen, but the freedom Ainsworth possesses as a man to be able to move across borders on his own, to see the world and expand his mind. When Ainsworth’s second wife, Sarah, wishes to attend the Tichborne trial, she must seek permission, and only receives Ainsworth’s permission because Eliza agrees to act as a chaperone.

For me, that was the origami trick that puffed this novel into a shape. Like Virginia Woolf advocating something as simple as space – the independence of a room of one’s own – as necessary for a woman to produce prose, freedom is contingent for a full humanity, yet it may be curtailed on the basis of gender, or race or even wealth. The Claimant’s case may be bogus, but it is no less aspirational than Edward Tichborne’s decision to set aside his own identity and become a Doughty in order to inherit the wealth and estate of a distant cousin.

Each character has some association with notions of freedom and its attendant moral dilemmas. The Tichborne wealth is predicated upon slavery. Andrew Bogle has been a slave and seems willing to lie to overturn the historic injustice done to him by an imperial system and by the Tichborne’s specifically. And just as Edward Tichborne/Doughty is no less aspirational than the Claimant, neither is Eliza in her own desire for money in her hope for independence. Eliza is disillusioned with her life and wants more freedom as a woman. But what is she to do to remain moral when she receives an inheritance from her deceased husband’s estate that she knows has potential other claimants?

We sense as we read that there are certain ‘truths’ in this novel that transcend facts. These ‘truths’ attend issues like slavery, the right of women, the aspirations of the working class and freedom. Henry Bogle, Andrew Bogle’s son, tells Eliza that freedom is not contingent upon it being granted: “my freedom is as fully my inheritance as it is any man’s.” His sense of freedom echoes Rousseau – “Man is born free and everywhere he is in chains” – and his choice of word, “inheritance”, seems loaded. The whole Tichborne case is essentially about inheritance – about money – but Henry Bogle is making a moral argument based upon the notion of human rights rather than a legal claim: “But it is not the prisoner’s right to open his cell that is in question, Mrs Touchet! It is the gaoler’s fraud in claiming to hold a man prisoner in the first place.” Henry’s words ring the keynotes of the novel. Where lies the fraud when it is an act against the systemic injustice of the system?

The issue of fraudulence, naturally, runs right through the novel. The Claimant might be a fraud. But William Ainsworth is no less so, writing upon subjects he knows nothing about and is too lazy to study. He introduces idioms of speech he has no experience with into the mouths of his characters in imitation of other writers. Cruickshank, the popular illustrator is something of a fraud, too, because he charges others with this fault: he claims he gave both Ainsworth and Dickens the ideas for their most popular novels. Even Eliza must face this prospect when she initially chooses to conceal from others the annuity she has received from her husband’s will, to the possible detriment of others.

Smith’s narrative exposes these small fraudulences, but the essential fraud lies with wealth, class and the empire upon which they are predicated. Marriage for the wealthy is an act of “adding up” not just of reputation but of wealth. The maintenance of the empire is merely the protection of the sources of wealth. Slavery may be abolished in Jamaica, which is the source of Tichborne wealth, but a wealthy author like Dickens is willing to support Governor Eyre’s extra-judicial execution of over four hundred activists there, despite his being “ever a friend of the weak and the poor”. The immoral dimension of slavery and repression is hard to project above the exigencies of economics. There is an underlying implication throughout the novel that wealth and its acquisition may be morally fraudulent.

Despite Zadie Smith’s reservations about historical fiction, and despite some minor lapses in the cohesiveness of the narrative, her first foray into the genre is both fascinating for its historical minutiae, as well as being an accessible story and of interest to modern audiences.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed Facebook

Facebook Instagram

Instagram YouTube

YouTube Subscribe to our Newsletter

Subscribe to our Newsletter