The Fifth Season is a novel with an audacious subject: it’s the end of the world!

Yeah, I know …

Many cults have predicted the end of the world, many supervillains in our stories seem intent on ending the world (although who the hell knows what they get out of that?) and general doomsaying pervades our culture to the point that we are likely to yawn a little because – let’s face it – when confronted with an event so cataclysmic, so difficult to imagine happening (yet maybe not so), and with no means by which you or me or the average fantasy-reading junky can forestall this possibility, then a little yawn is forgivable. But I’m not talking about a world-ending event like the destruction of Alderaan by Governor Moff Tarkin’s imperial government in Star Wars. Well, not entirely. N.K. Jemison is not so crass. When nations or empires fall, the last gasp is bound to have been foreshadowed by a long decline, like Rome finally succumbing to the Visigoths. There is a story to every death and The Fifth Season, the first book in Jemisin’s Broken Earth Trilogy, is the beginning of that story. And the thing is, the end of the world is not always the end of the world, at least as we imagine it in science fiction stories with impossibly powerful lasers. One impression we get from Jemisin’s writing is that we humans are an incredibly self-centred bunch, in which our own ending is promoted as a cataclysm:

This is what you must remember: the ending of one story is just the beginning of another. This happened before, after all. People die. Old orders pass. New societies are born. When we say “the world has ended,” it’s usually a lie, because the planet is just fine.

This is a story of Earth set far into the future. It has survived the worst we have done to it, but it is now in a state of unstable tectonic movement and seasonal change. So, it’s a post-apocalyptic story with a fantasy twist. Jemisin is imagining something far different from Mad Max. Her world is what has emerged long after the society we now have has been destroyed. Even so, the ending of Jemisin’s prologue signals a destruction as painful and slow as the Roman Empire’s and as complete as Alderaan’s. By paraphrasing T.S. Eliot’s poem ‘The Hollow Men’, (“This is the way the world ends / For the last time”) Jemisin suggests a destruction that is complete and terrible: a destruction in which the planet is not “just fine”, and the finality of its ending is unanticipated, because this is the world of The Stillness in which cycles of destruction and regrowth are dreaded, but accepted as normal.

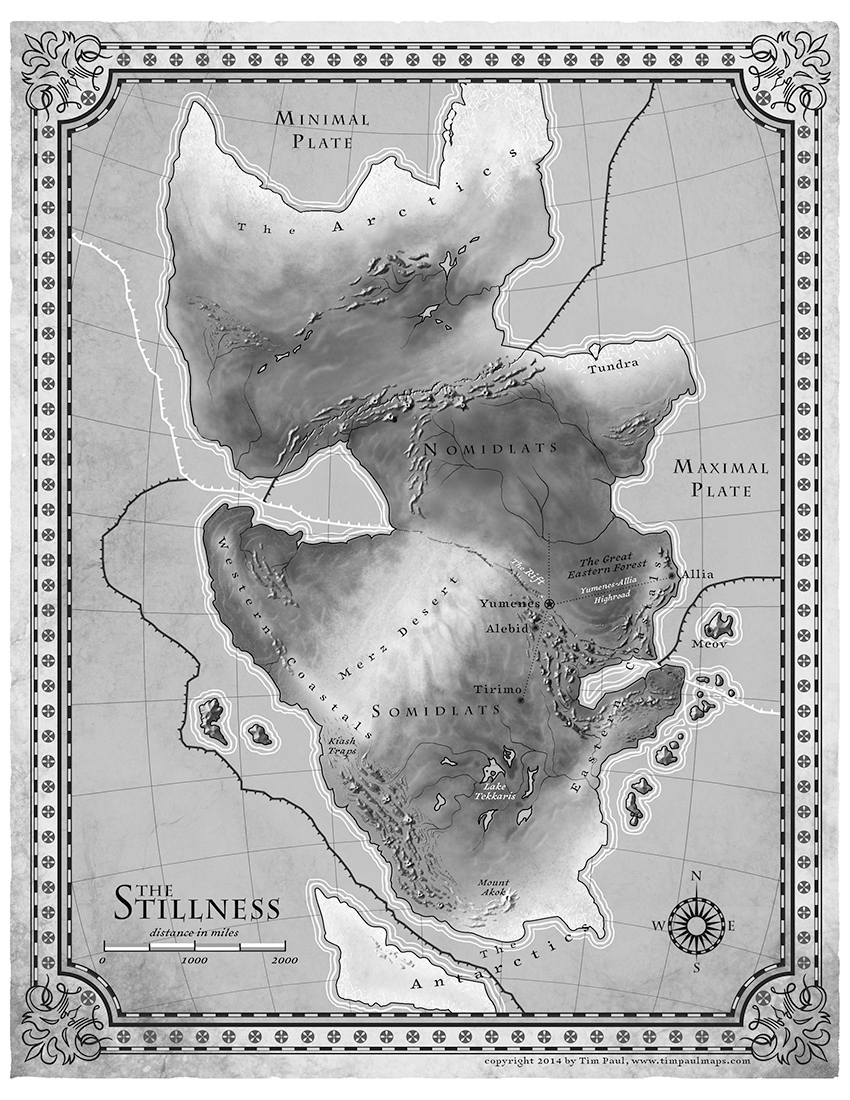

The Stillness, we are told, “is a land of quiet and bitter irony.” Certainly, its name is a misnomer. At the moment this world is mostly a single continent (see the map), but it is a changeable place: “It moves a lot, this land. Like an old man lying restlessly abed it heaves and sighs, puckers and farts, yawns and swallows.” At one point in its past the world consisted of several continents – our world – and one day it will split apart again. The story feels like it could be something from our own pre-history, like we’re reading the story of a make-believe people who lived at the time of Pangaea in a period when the Earth was far less stable. But this world is a result of our own civilisation: a ‘deadciv’ in the parlance of The Stillness. The Earth’s continental plates press against one another, producing earthquakes, tsunamis and volcanic activity that, every so often in its human history, has brought about destructive ‘fifth seasons’ which cause suffering, death and even the collapse of ‘comms’ – communities – that always try to prepare for the possibility of another Season and the death and violence which may ensue, but do not always survive.

Like any human civilisation, culture, government and power stem from the circumstances of the world. In our own world, politics and power historically have been organised around the problem of scarcity and the competition to acquire land and resources, apart from ideological or religious tenets which also lead to conflict. By the end of The Fifth Season, the world seems emptier. We know who the players are but not necessarily what their ultimate goals are. In The Stillness the locus of conflict resides with the power of the orogenes who can commune with the earth, tap its latent power, and cause seismic ruptures at will: they can quell earth tremors but they also have the potential to cause them. Across The Stillness a series of Outposts are manned by orogenes who quell seismic activity in their region. Balancing their power are the Guardians, originally children of orogene parents who have no power of orogeny, themselves. Fitted with an implant that can disrupt orogene power, they guard orogenes in the Fulcrum, a city within the city of Yumenes, where orogenes are trained to control their power so that they might prevent disasters and serve the interests of their comms, and where they are indoctrinated to accept their place in the world. It is a world in which orogenes have an ultimate power and can do much good, but they are also feared and reviled by communities where they are known by the derogatory term, ‘roggas.’ Their communities will as likely kill them if they are discovered while still children, well before the Guardians can take them into their care, because orogenes also have the power to do much harm. And because people have been taught to fear them. The story of Misalem, for instance, is the story of a powerful orogene who threatens to destroy a city because he is mad or evil. Forget that there are holes in this piece of lore. You can fill in the blanks if you read the book. The point is, the lore and legends of this land serve to control the power of orogenes as much as any direct force used against them. As this novel begins, Essun, an orogene who keeps her power a secret, has just discovered her son, Uche, murdered by her husband. Jija has been raised like most to fear orogenes, and he has just realised what their son is. The Guardian, Schaffa, who takes Damaya from her home to be trained at the Fulcrum, expresses his love and admiration for the young girl whom he will mentor. But first he breaks the bones in her hand to make her understand who is in charge. An orogene who cannot be controlled, and who cannot learn to control themself and serve the Fulcrum will be readily killed by their loving Guardian when it is needed. In essence, orogenes are powerful, but they are controlled, exploited even, and for many, even enslaved.

This is a world in which politics is in conflict with nature, itself, and its primary goals, as expressed in the novel, are to find the means of maintaining power over those who have real power. This includes the orogenes, naturally, who are aligned with nature, but ultimately that control extends to the earth itself, expressed in the anthropomorphic legend of Father Earth. Father Earth is a real bastard. At least that’s what is expressed in the language of the people of The Stillness, whose imprecations against ‘Evil Earth’ pepper their speech, often as expletives. And there is a fear that orogenes are weapons not of the Fulcrum, “but of the hateful waiting planet beneath their feet.” In the lore of The Stillness, Father Earth was a conscious being who created humans as a necessary tool: “Clever hands for making things and clever minds for solving problems …”; but turned against humankind when they slipped from his control.

This is the world of The Fifth Season and it is a fascinating achievement. But the thing about The Fifth Season is that this is a book that is difficult to discuss in terms of its plot without bumping into some major spoilers for readers who are yet to read it. All I can say is that I found this book a refreshingly different experience to reading other fantasies – I admit I don’t read many, and it also has elements of sci fi – while it still remained firmly within the fantasy genre through its world-building and its own version of ‘magic’ – orogeny – around which the story is built. For this reason, you won’t read anything here about the story of major characters like Syenite or Alabaster, two powerful orogenes, or of their mission, or the strange Stone Eaters or the obelisks, or many other characters like Hoa, Tonkee and Innon, who are instrumental to the main plot of the novel. When you imagine the plot which I am not discussing you are free to think of the rebel alliance from Star Wars because there is some truth in that, even though it is quite wrong to make the comparison. Like Luke Skywalker, we have an origin story here, too; of a character coming into their powers, and what happens when they learn that the world they live in is not quite what they thought it was.

I’m going to leave discussing the plot as vague as that.

But what remains most interesting throughout the book is that problem of power: real power and power acquired through politics, manipulation and misinformation. The lore of the land is quoted at the end of most chapters. This and the two appendixes at the end are useful guides to the world of The Stillness. Of interest, for me, is the term ‘stonelore’. We learn in the Prologue that the lore and legend of this world was originally written in stone, quite literally: “Chiselled words are absolute.” Stonelore tells the story of The Stillness; of its origins and its people, as well as the many ‘Seasons’ which have occurred to destroy and recreate the world, and it teaches the people of The Stillness not to trust orogenes outside the Fulcrum’s control. It is a form of absolutism – chiselled in stone – designed to create a sense of community, but also to control and even allow the enslavement of members in that community through vilification and fear. Alabaster tells Syenite (I know I said I would not discuss these characters, but even words written in stone may change it seems) “They kill us because they have stonelore telling them at every turn that we’re born evil.” Alabaster, an orogene at the level of ten rings, the most powerful in the world, speaks of stone tablets damaged in the past because they may not have conformed to the needs of the powerful, or other stones found in the ‘deadcivs’ (comms or cities destroyed by previous Seasons) which have produced stones that drastically contradict the lore now taught.

This is a neat paradox in a world called ‘The Stillness’ which is everchanging. The notion that lore and truth are embodied in stone is paradoxical, since stone and the earth are in a constant state of flux in The Stillness. This may be ostensibly a fantasy novel, but Jemisin has neatly touched upon the political underpinnings of law, of convention and belief in our own world, which so often presume an immutable authority as their basis, whether this be through God, truths that are held to be ‘self evident’, or other doctrines upon which power is predicated. It did not escape me that the ‘evil’, ‘mad’ Misalem (representing “the Misalems of the world”) is a near homophone for Muslims. The stories we tell are powerful, especially when told as a means to control or vilify others.

If none of this has convinced you that The Fifth Season is a book worth taking a look at, you may wish to consider its reception in the literary world. A book winning an award is not a reason to read a book, but awards exist because they are nevertheless persuasive for sales. If you consider yourself Jemisin-curious, you may have heard of the writer’s impressive reputation. But if you are yet to be enlightened, here it is: The Fifth Season won the Hugo Award in 2016, and the subsequent books in the series, The Obelisk Gate and The Stone Sky, also won it. It was the first time ever that an author won the award three years in succession, and it was the first trilogy ever to have been awarded the Hugo for each volume in a series. Jemisin has now won the Hugo five times (also for Best Novelette, Emergency Skin (2020), and for Best Graphic Story, Far Sector (2022)). She has also won the Locus and Nebula awards, and all her books have either won or been nominated for the Hugo, Nebula and Locus Awards at the time of writing.

But that doesn’t necessarily mean you, as a reader, will connect with this book. All I can offer you is a glimpse into this world, as I have done, and a peek at the characters as they go about their business, as through the chink of a door, while leaving the main attractions for you to discover, in the room beyond. And finally, I wish to give you a sense that this is sophisticated fantasy/sci fi novel, but that it is also a window into our own world: a window on how we treat the environment now, and what concerns we should have about that; and the means by which power is created and maintained. These are not all the book is about, but they are so much of what this book is about.

The Broken Earth Trilogy

RSS Feed

RSS Feed Facebook

Facebook Instagram

Instagram YouTube

YouTube Subscribe to our Newsletter

Subscribe to our Newsletter

No one has commented yet. Be the first!