You once made the observation that some words were considered more important than others simply because they were written down. You were arguing that by default the words of educated men were more important than the words of the uneducated classes, women among them. Do what you are good at, my dear Esme: keep considering the words we use and record. Once the question of women's political suffrage has been dealt with, less obvious inequalities will need to be exposed. Without realising it, you are already working for the cause.

Edith ‘Ditte’ Thompson to Esme Nicoll, page 271

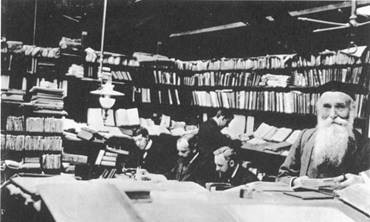

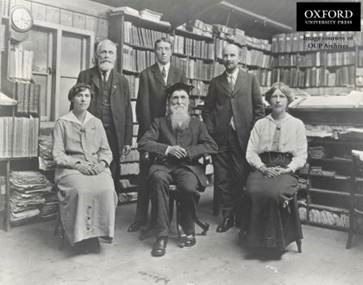

The compilation of the Oxford English Dictionary commenced in 1857 when the Unregistered Words Committee of the Philological Society of London called for a new dictionary to succeed Samuel Johnson's 1755 Dictionary of the English Language. This took a lot longer than had been first anticipated and neither of the first two editors made much progress. Twenty-two years later, Dr James Murray was appointed as its third editor, and progress was finally made on the work, with the first fascicle (A to Ant) published in 1884. The first of the eventual twelve volumes was published in 1888, containing A to B. The final volume was not published until 1928. One word which should have been in that first A-B volume in 1888 was ‘Bondmaid’, an archaic word meaning slave girl. In 1901, an enquiry from a subscriber revealed that ‘Bondmaid’ had been accidentally left out of the dictionary. Many other words were missing from the A-B volume, but these were deliberate omissions. ‘Bondmaid’ had been intended for inclusion but was somehow lost. As Dr Murray wrote in a letter to a contributor Not one of the thirty people (at least) who saw the work at various stages between MS. And electrotyped pages noticed the omission. The phenomenon is absolutely inexplicable, and with our minute organisation one would have said absolutely impossible; I hope also absolutely unparalleled.

‘Bondmaid’ was eventually published in the 1933 Supplement to the Dictionary.

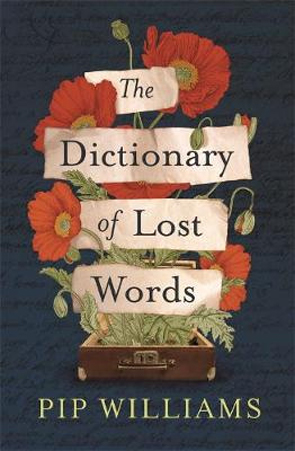

Pip Williams takes this missing word and uses it form the basis of The Dictionary of Lost Words. Against the historic backdrop of Dr Murray's Scriptorium, she introduces Esme Nicoll. Esme is the daughter of one of Dr Murray's assistants. She is motherless, and her father brings her to the Scriptorium with him each day. She plays under the table while her father and others work on the slips which make up the contributions to the Dictionary. One day, when Esme is about six, a slip falls down under the table. Other words have fallen before and have been reclaimed by the person who dropped them. This word, ‘Bondmaid’, is not claimed and Esme puts it in her pocket. It is only a single page, not a bundle of pages as are most of the words earmarked for inclusion in the Dictionary. Esme knows that the Scriptorium receives many duplicates of words and thinks that this page must be one of the duplicates and is superfluous to need (a phrase she hears many times as duplicate slips are thrown in the fire). It is the first of many words Esme collects over the years, many of them words related to female experiences, rejected by the middle-class men who are the main compilers of the Dictionary.

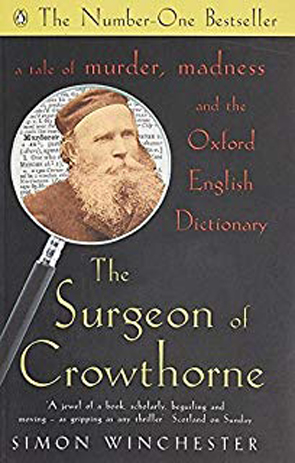

I have previously reviewed The Surgeon of Crowthorne by Simon Winchester which tells the story of the compilation of the Dictionary. But that book focusses on Dr Murray and on one of the most prolific and eccentric contributors to the Dictionary, Dr William Minor. While an excellent book, it does give the impression that the Dictionary was a male only affair. It doesn't have much to say on the women who also worked on it, such as Edith Thompson who was a historian and author, as well as being a consultant for the Dictionary. She and her sister Elizabeth (a writer) were credited with over 15,000 quotations for the A-B volume in 1888. She was also a sub-editor for "C" and proofread from "D" onwards. In The Dictionary of Lost Words, she becomes the character "Ditte". She had been a friend of Esme's mother, and becomes Esme's godmother, and later a friend and mentor.

Esme grows up with a love of words and their meanings, and is uninterested in pursuing the type of life which would be typical for a woman of her class. She is also uninterested in marriage, preferring to work with her father on the Dictionary. But while she loves her work, Esme also notices that some words are left out, and that there is a distinct bias in the words included. Each one individually doesn't mean much, but overall, they add to reinforce the idea that words connected to men's endeavours are of more importance than those connected with women. The words which refer to women that are included are most often those that describe a woman's function in relation to others, such as ‘wife’ or ‘mother’ or ‘whore’ or ‘scold’. As Orwell tells us in Nineteen Eighty-Four, controlling language is a way of controlling thought. If the only words deemed to be of importance are the words of men, the lives and actions of women become of lesser of importance. Women are kept at a level subservient to men. An early example in the book is the word ‘literately’, meaning ‘learnedly’. Dr Murray rejects the word for inclusion in the Dictionary, as it only has one example, in a book by a woman. However, he accepts ‘literata’, another word which is sourced from only one book, but written by a man. At another point, a servant uses the term ‘expecting’ for a pregnant woman. Esme looks in D-E, finds the word but not this meaning. ‘Menstruation’ is in the Dictionary, but all its meanings relate to ‘unclean’ and ‘polluting’. Words commonly used but not written anywhere are not included in the Dictionary, such as ‘knackered’, a word Esme realises contains more meaning that ‘tired’. Esme begins to feel that these words are just as important as the ones Dr Murray collects, and sets out to collect all of the lost words, the words which would not be captured by the Dictionary.

Her quest brings her into contact with the suffragette movement, and she realises her work is more important than she first thought. Even if women do eventually get the vote, she realises that the fight will need to continue to address many different inequalities in her world. Inequalities such as access to education. Elsie Murray for example completes her studies for a degree in 1909, but as she does not wear trousers, she is not allowed to graduate.

Even the suffragette movement has an inbuilt bias. As Esme's friend Lizzie, servant to the Murray's observes at one point - All that ruckus the suffragettes make, it isn't for women like her and me. It's for ladies with means, and such ladies will always want someone else to scrub their floors and empty their pots … If they get the vote, I’ll still be Mrs Murray's bondmaid.

When women were first given the right to vote in the UK in 1918, it was restricted to women over the age of thirty who met the minimum property qualification. It was not until 1928 that UK women were given an equal franchise with men.

Overall, this is an excellent book for anyone interested in words, the ideas behind the words we choose to give importance to, and in the biases inherent in our language. The backdrop of the book is a rapidly changing world, with the suffragette movement growing in strength and the First World War looming, both of which impact on Esme's world as she grows to adulthood. Pip Williams has taken a minor incident from the history of The Oxford English Dictionary and has crafted a beautiful book out it. Highly recommended.

Related Book Reviewed on this Website:

RSS Feed

RSS Feed Facebook

Facebook Instagram

Instagram YouTube

YouTube Subscribe to our Newsletter

Subscribe to our Newsletter

No one has commented yet. Be the first!