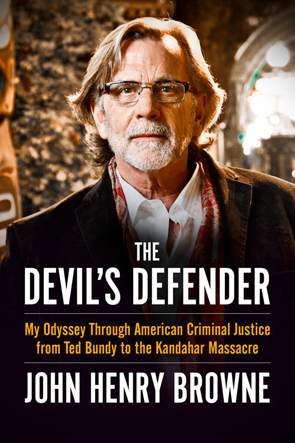

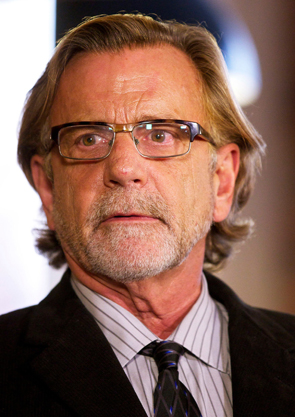

Oh hey, why not read a memoir to break up your monotonous staccato of existence? How about a neurosurgeon who dices up blameless children in his introspection-heavy book Do no Harm? What about a dashing tale of special forces gallivanting in Vietnam, We Few: U.S. Special Forces in Vietnam? I read The Devil’s Defender: My Odyssey through American Criminal Justice from Ted Bundy to the Kandahar Massacre by lawyer John Henry Browne. It’s an incredible read. Browne was in a Guardian video that followed lawyers from defence counsels of particularly notorious murder cases. The attorneys introduced in the video all had this glassy countenance, distantly reflecting on their intersection with a terrible crime, ones instantly identifiable with surnames alone: Ng, Venables, Bundy. Browne was there looking like a man who jizzes cognac, adorned with rouge scarf and horn-rimmed glasses. He’s 6'4" (193 centimetres) with big articulate eyes like a counterfeit Jeff Goldblum, the only trace of aging being a sagging mouthpiece. He looks and sounds like the single uncle who chooses his words carefully out of a constantly swirling mental pool.

The whiplash of Marsh’s sullen introspection to the gung-ho obliviousness of Brokhausen made me weary of autobiographies in general. Will I get a lap full of emotional baggage or pointless dribble about “estrogen kitties”? It turns out, neither, but that doesn't mean the book isn’t thoughtless, a stream of objective bullet points about the legal process. You can tell it’s a recollection of events that have been stewing within him for a while. And Browne’s thoughts, expressed with a fierce intelligence, are carried with a certain confidence that makes you inherently trust his intuitions.

Trusting lawyers. That's a bit of an oxymoron isn't it? We sort of expect them to be the world’s largest invertebrates, soulless grifters of the system. Americans’ contempt for attorneys transcends black liquorice and communism. I remember angrily staring at the back of the attorney’s head during jury duty. I didn't know them. I didn't want to be there. All I knew was that I must hate with the same indignant passion as racists.

One element Browne does well is making his job look not just morally admissible, but entertaining. To most people the formalities and the choreographed dance of affidavits and appellants retains all the thrill of decaffeinated coffee. Personally, jury duty was so achingly boring I was looking for the sharpest object in the room I could drive through my neck. Only the judge cracking jokes with the security officers could compare in raw entertainment value with imagining my crimson streams splashing across horrified onlookers. Court is a game of selling a convincing narrative to the jury. Cases are stripped down to established truths and ambiguities to be questioned. Browne compares the whole ordeal to theatre, an outlook consistent with his reputation as an aggressive and charismatic criminal defence attorney. One of his closing statements was, “Ladies and gentlemen, would you leave your dog with that woman for the weekend?” You would expect the judge himself to give Browne a thorough fatherly spanking but his client was acquitted.

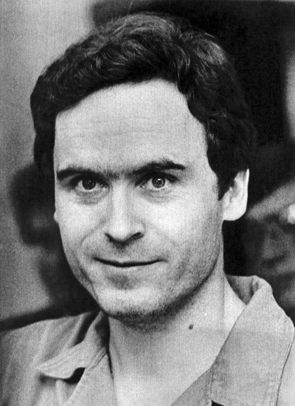

The main appeal of this book is of course Browne’s role as serial killer Ted Bundy’s legal counsel. His dealings with Bundy span several years from recollections during in-person prison visits or mail correspondence, most of it presented whole in the latter half of the book. Like in court, Browne does a choreographed dance, this time with his client. The relationship is a simple attorney-client affair, and Browne doesn’t delude himself in thinking Bundy is anything but a manipulative sociopath. But despite this wall that their roles necessitate, the instances at which their personal lives intersect include some perineum-tightening moments. In one instance, Bundy imitates Browne’s outfit by purchasing and wearing identical clothing. The gradual transition in Bundy’s mannerisms and the personal myth of innocence that he tries to maintain throughout the legal proceedings is an uncomfortable point.

For true crime fans this book carries a lot of appeal, but not in the contemporary sense. It lacks lurid crime scene descriptions or play-by-play recollections on how Bundy must have killed. The book also isn’t imbued with that voyeuristic appetite suppressant prose so common today, a whiff of exploitation that emanates from both books and podcasts. The human drama is there unadulterated, and it is Browne’s empathy for his clients and the victims, instead, that permeates the pages, its apogee being the barefoot bandit case.

There’s a sort of visceral response most us have when it comes to the placidity of a horrible crime’s court proceedings. When there’s little ambiguity in the defendant’s guilt the whole song and dance seems superficial, unnecessary even. And for most of us, I think, with the severity of the crime, it transforms into a moral issue. We all revert to puddle-drinking Neanderthals the moment abhorrent headlines are smeared across the box. We suddenly stop caring about bureaucratic overspending or miscarriages of justice. We want justice to be done and bending the rules isn’t as unjustifiable as we told ourselves. According to conservative US estimates, 4% of executed prisoners have been innocent. If a cup of milk has a 4% change of giving me norovirus I'd hammer throw the jug into a neighbour’s yard. And these aspects of a fallible system are what has carried Browne to fight for his clients, from flimsy cases to corrupt police.

Browne, for all his paternalistic reassurances about the legal system, even struggles with Bundy’s case. His budding passion about social justice, his reverence for JFK, his role in representing detained civil rights protestors and the Black Panthers, and his formative transformation in fighting a fallible justice system, are all reduced to the same primitive urges, as with all of us. Browne is aware that more murders occurred in Florida after Bundy’s first prison escape, naming off successive victims with uncomfortable clarity. He even wonders if he should have smuggled in a gun and shot Bundy himself, a stark contrast to his long-standing convictions about civic rights and the death penalty. It’s a far cry from his trail-blazing domestic violence cases or his role in reforming Oregon’s prisons by experiencing incarceration first-hand.

The Devil’s Defender is a compelling memoir, a sincere and introspective look into an attorney’s work within the confines of a flawed justice system and a tested moral compass. His righteous and at times arrogant recollections are softened by his furious introspection and sincere motives in defending the indefensible.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed Facebook

Facebook Instagram

Instagram YouTube

YouTube Subscribe to our Newsletter

Subscribe to our Newsletter

No one has commented yet. Be the first!