Before you start, some other resources on this website

The Count of Monte Cristo was first published in the Journal des Débats in eighteen parts, from 28 August 1844 to 15 January 1846. It’s a long novel which may daunt modern readers. My World Clouds Classic edition, the version I read, comes in at 1055 pages of closely packed small type. A penguin edition I also have tops out at 1243 pages. Estimations of the novel’s word count vary on the internet, and that might be, in part, due to some abridged editions available. I estimate its length at close to 500,000 words. Apart from its length, the novel also has a host of major and minor characters, which is why, before I get into this review, I will direct you to another page on this website you may wish to look at later. It has links to a character map, brief character descriptions, as well as a chapter by chapter summary of the entire novel for those interested, and who think this might help them in their reading.

[Visit The Count of Monte Cristo Page]

Film versions and the novel

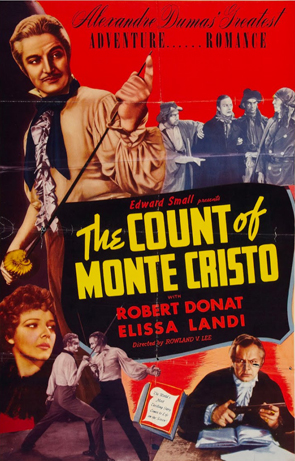

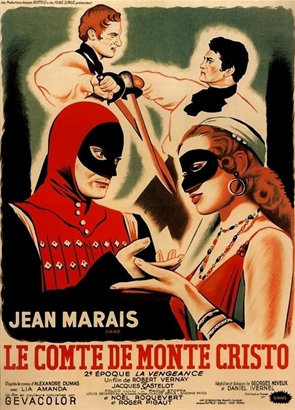

I looked up film versions of The Count of Monte Cristo before I started this review. This is, in part, because my path to the novel was through James McTeigue’s 2005 dystopian thriller, V for Vendetta. In that movie V, a former inmate at a government facility, escapes and transforms into a sophisticate bent on revenge against those who put him there. But V is more than a revenger. He is also a revolutionary determined to bring down a repressive government. He wears a Guy Fawkes mask to hide his identity, as well as the terrible scars he acquired in a fire at the government facility. This becomes a symbol of his cause. V hides out in a chamber populated by all manner of cultural artefacts banned by the government. V takes Robert Donat’s portrayal of the Count as his model, from the 1934 film version of The Count of Monte Cristo. He replicates a scene of Donat’s sword play during the film, while watching the movie. (Click here for a review of Alan Moore’s graphic novel that inspired the V for Vendetta film). There have been at least nine major films of The Count of Monte Cristo and three television series based on Dumas’s book (although I suspect there are more than I’m finding) as well as sequels or spin-offs, such as the 1940 Son of Monte Cristo, starring Louis Hayward, and The Wife of Monte Cristo from 1946. That film is set during the period after the novel when the Count becomes a kind of masked superhero fighting for ordinary Parisians. When he is wounded, his wife (Haidee from the novel) takes over his masked role. From what I can tell – because I certainly have not watched all these films, only snippets on YouTube – is that there is an emphasis on swordplay to resolve the plot. Certainly, in V for Vendetta, V is adept with a sword. What is interesting in this is the vast difference between the way a story is told in novels and in film. Or, more precisely, how the need for visual excitement in film can distort a story and turn it into something else in popular culture. How, after all, could a new Monte Cristo film be made that doesn’t have sword play after Donat’s version? Donat’s 1934 film wasn’t the Count’s first appearance – there were two silent films before that – but Donat’s version created that expectation in this character, I think.

The fact is – and this is the reason for this long digressive opening – there is no sword play in the novel, nor is there even a duel with pistols. The 1975 movie version with Richard Chamberlain, for instance, has the Count face off against Albert de Morcerf in a duel. Like Hamilton, he deliberately aims his pistol wide and Albert de Morcerf honourably does the same. But in the novel, Albert challenges Beauchamp and then M.Danglars to duel him for the sake of his father’s honour. When it becomes apparent to him that the Count is the man he is really after, he challenges him to a duel with pistols. The Count is morose. He cannot kill Albert, the son of his former lover, Mme Morcerf (also known as Mercedes), nor can he refuse the challenge out of honour. He is resolved to die at Albert’s hand, which will end the long years of effort and planning to achieve his revenge. But Albert calls off the duel beforehand when he discovers that the Count was justified in his actions against his father. The Count is relieved. In the eyes of Albert’s friends, it is a shameful moment. That is as close as the novel comes to duelling of any sort. But if that kind of action has been your expectation, it has come from the story’s film history, not from Dumas. And this is not unimportant; it is not pedantry. By adding the swordplay and other action, film versions change the character of the Count, misrepresent his philosophical approach to his undertaking, and deny their audience the subtle appropriateness of each revenge undertaken. In fact, the character in the films, one might argue, is closer to Dumas’s source material. Dumas based his novel on the true-life story of Francois Picaud, who was imprisoned in 1807 under circumstances that are closely mirrored in Dumas’s plot. He was released after Napoleon’s defeat and undertook a series of revenges, stabbing two victims, burning the café of another and even resorting to poison. Yet Dumas’s Count does not kill anyone. He finds out their secrets, he understands their character, and he uses his knowledge and wealth to set them on a path to destroy themselves.

Plot outline

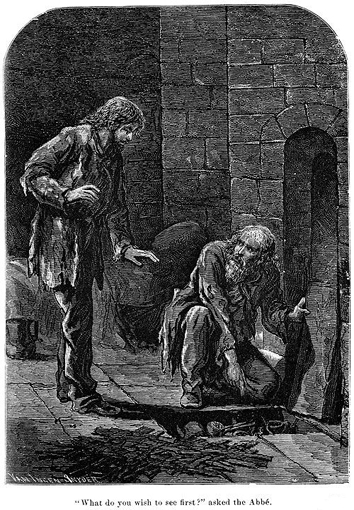

I’ve written a full summary of the plot which you can find by following the link above, but for the purposes of this review, I’ll offer a shorter version. The novel is set during the period of the Bourbon Restoration, roughly 1815 through to about 1840. When the novel begins, Napoleon has been exiled to the island of Elba. When he escapes he makes his last bid for power, commonly known as The Hundred Days, before Napoleon’s final defeat. The novel begins with Edmond Dantes captaining his employer’s ship back to harbour after the ship’s captain unexpectedly dies. But before his return he visits the island of Elba where Napoleon now resides, to honour his captain’s dying wish, to deliver a package to Marshal Bertrand. Dantes is not political, and does not anticipate the trouble this will cause. At the hands of a jealous lover and a jealous shipmate, along with the self-interested decision of a magistrate, he will be wrongfully sent to the island prison, Chateau d’If, where he will spend the next 14 years of his life. It is here that Edmond befriends the Abbe Faria. Faria educates Edmond, tells him of a great fortune hidden on the island of Monte Cristo, and eventually provides him the means to escape. When Edmond escapes, he finds the vast fortune, adopts a new identity, the Count of Monte Cristo, develops a large support network of allies, and undertakes a long process to insinuate himself into the lives of those responsible for his imprisonment. Through his new identity, he begins the machinations by which he will ruin his enemies. Against a banker who prides himself on his financial acumen, he will attack his finances; against a decorated soldier, he will attack his reputation; and against a man of the law, he will seek to criminalise him and ruin his family.

Philosophical underpinnings of the book

Edmond Dantes, as the Count of Monte Cristo, uses his brains and his wealth to achieve his ends, not his sword or pistol. He is dangerous because he knows more about each of his opponents than they believe anyone could know. His wealth buys him information, buys him access and provides him with the means to enact his plans. He is an arch manipulator because he understands those whom he targets and he is patient. His mantra is ‘wait and hope’. Sophisticated Parisian society seems parochial compared to Dantes’s breadth of knowledge, his foreign tastes and foreign companions. When M. de Villefort threatens him with the law, Edmond demonstrates a greater knowledge not only of French law, but laws from every place in which he has resided. When he speaks to Villefort’s wife about poisons, it is clear he has an unnerving knowledge of poisons and their application. He is dismissive of European poisoners who source their poisons from too many places and administer them directly. He speaks of the Abbe Adelmonte, who would poison a lettuce leaf which he would feed it to a rabbit. And when the rabbit died, the carcase of the rabbit would be fed to another animal, and so on for up to five different animals, before the meat was finally served to a victim. By the time the victim died, there was no evidence that could incriminate the poisoner. The conversation is not only instructive for Mme Villefort, who will become a poisoner of other members of her family, but it serves as a neat metaphor for the kind of revenge the Count intends. When the Count speaks to Franz d’Epinay about revenge, he expresses his feeling that the guillotine or killing a man in a duel is too quick a death to satisfy the needs of revenge. He advocates the principle of an eye for an eye. If the crime has inflicted slow and torturous pain, that is what must be administered in return.

This is important to understand the philosophical underpinnings of the book. Dumas is writing in a period in which the tenets of Christianity are still held strongly, but in which society has been changed by the French Revolution and the tenets of the Enlightenment. Edmond is a man of the Enlightenment, with a pluralistic attitude to culture and class. He seeks enlightenment from Eastern culture, is learned in many areas and speaks several languages. Yet Edmond Dantes is an uneasy amalgam of different philosophical positions. His return to society is through the agency of wealth, education and patience. He values knowledge and learning from the modern world – in one chapter he employs the new telegraph system to stunning effect - but guiding principles are based upon Christian religious precepts. While Dantes has overcome the horrors of imprisonment, he believes he has done this through God’s Providence. The treasure he finds seems to be a demonstration of this, but he also looks to God’s Providence through the course of his revenge plans, too. Indeed, some of his plans are far more sophisticated than sticking a sword in someone would require, so the chances that they might come undone, or that a means might not be found to achieve them, might make it seem reasonable to accept the hand of Providence is at work. When one aspect of Dantes’s revenge goes horribly wrong – the revenge extends to those he did not intend – he returns to the decommissioned prison, Chateau d’If, from which he escaped years before, and seeks a sign that he should continue down his path of revenge; that he is still divinely commissioned. Another religious precept tested by the Count’s actions is the notion that the sins of the father are visited upon the son. It is another Old Testament idea, that the action of sin can have consequences from one generation to another, and that sinfulness can be inherited. The Count of Monte Cristo is a generational book, so it lends itself easily to this problem. M.Noirtier, Villefort’s father, has murdered a man while president of the Bonaparte Club. While Villefort does not hold the same political ideas as his father, Villefort is guilty of having tried to murder his own infant son. That son, having been rescued and grown up, unknown to Villefort, has become a criminal. This is an essentialist view of humanity, that we are what we are, and seems to condemn humans to a universe in which nature cannot be overcome. This may be problematic for modern readers. The novel also measures the idea of sins of the father against the range of the Count’s revenge. A revenge that seeks restitution for a wrong done so many years ago cannot help involving others, such as children, who were not alive when the wrongdoing occurred. As a result, Eugenie, the daughter of M.Danglars, risks being married to a criminal and financially ruined. Valentine risks being poisoned by her own mother. Albert de Morcerf’s reputation is at risk, not to mention his own life, in his vain but noble attempts to protect his family’s reputation. For these reasons, as readers, we see that there should be limits to revenge, but we must also accept, if we are to traverse the Count’s world and remain on his side – a willing suspension of disbelief, if you will – that there are moralities that transcend human law; that a man can represent more than an avenging hand, but also God’s justice. To this extent, the Count’s moral universe is at odds with secular values and Enlightenment principles.

To read this novel, then, we understand that this is a world view we accept, at least while we remain within the book's covers, if we wish to be swept along by the entertainment: to credit that the moral righteousness of the Count’s course is a matter of Providence that supersedes human laws (if you consider the tenets of some forms of modern terrorism, you might understand why I feel this is an unsettling proposition). Therefore, if one accepts that finding the treasure is a matter of Providence, then one may also accept God’s hand in each of the Count’s undertakings. But that does not get us away from the fact that the Abbe Faria gives a detailed account of the history of the treasure – that its provenance is distinctly human – and that Dantes’s finding it and utilising it results from his own volition and intelligence. All, this becomes problematic to discuss in a review, because obvious rebuttles would occur to those who believe in Providence against these observations, and I’m merely pointing out the complexity of the character, not trying to argue a position. Nevertheless, there is also a fair question to be asked concerning the sins of fathers, when all children in this novel, excepting Benedetto, born from Villefort’s adulterous liaison with Mme Danglars, follow consistent moral compasses. It is a problem raised and asserted, but in the end, one feels Dumas, himself, may have been agnostic on the matter.

Why I recommend this book

The Count of Monte Cristo is a book of its time, but it still has a huge appeal for modern readers. I sometimes think that historical fiction, or books written in another historical period like this one, are a little bit like science fiction, in that they transport us to a different world with different values. In short, they can be escapist. The Count of Monte Cristo is a great escapist fantasy. It satisfies our basic desire, to see wrong righted, and our base desire, to see those who do wrong suffer for it. It follows a classic Hero’s Journey structure, giving it a familiar direction that appeals to a modern audience (think Star Wars: a terrible wrong is done – Luke’s aunt and uncle are killed by the Empire – and he uses his skill and bravery to balance that wrong with moral restitution; blowing up the Death Star). Given its length, the novel is not consistently enthralling. I found the scenes in the prison during the first section gripping. There is a lot of tension as Dantes’s sneaks between cells and plans an escape with Abbe Faria. There is always a chance they will be caught. The section where the Edmond Dantes first appears as the Count in Italy, during the Italian carnival season, is possibly the slowest point of the book, from the point of view of plot progression. Some important characters are introduced in this section – of most importance is Albert de Morcerf whom the Count needs to ingratiate himself with for his long-term plans – but the plot tends to meander with long descriptions of the Italian carnival, until Albert is kidnapped by Luigi Vampa and his bandits. Nevertheless, you get a great sense of the excitement of the Italian carnival while reading this section: the frustration of finding a carriage; the excitement of dressing up; the sexual frisson of participating; the colour and excitement in the streets. It’s still a good read and the scenes in Italy, particularly around the Colosseum and at Vampa’s hideout, are intriguing and entertaining. Even so, the long digression to tell the story of Vampa and his sweetheart, while interesting to read, now feels like padding after finishing the book, with a clear understanding of the broad outline of the plot.

However, once past this, the second half of the book commits the reader to the revenge plots and becomes quite gripping. And while it adheres to religious notions that some modern readers might question, it is also quite modern in other respects. Mme Danglars likes to bet on the stock market. The Count likes hashish and recommends its medicinal qualities (this aspect was removed in some abridged versions of the book). And Eugenie, daughter of M. and Mme Danglars, does not wish to marry. Rather, she wishes to be an independent artist, and is clearly having a romantic affair with her female music teacher. But most of all, I recommend this book simply because it is so good. The plot sometimes seems complex, but as you read you realise that you have been following long, satisfying story arcs. Digressions become meaningful.

As for the characters, they are sometimes of uneven development. This may be partly due to the way the novel is structured. It can easily be divided between the period before and during Dantes’ incarceration, along with his finding the treasure, and the period after that, about nine years after, in fact, when we first meet him again in Italy and he has become the Count. We assume his nine missing years have been devoted to his physical and intellectual transformation. Other characters have changed too. M.Danglars has become an aristocrat banker whom we hardly recognise. It is hard to account for his transformation. Fernand Mondego has become Count de Morcerf. His transformation is more fully realised than Danglars’s, but the changes are initially jarring. The love affair between Valentine and Maximilian may recall to modern readers the love affair between Cosette and Marius from Les Miserables: they even meet in the same style, like Pyramus and Thisbe, separated by a wall and gate, and sometimes they seem just as insipid from a modern point of view. Their love is uncomplicated, their attraction little understood. Sometimes, characters who are meant to be complex may seem too single-minded. Maximilian’s desire to commit suicide seems unrealistically determined and prolonged, while Albert’s determination to fight anyone and everyone over his father’s honour is possibly only understandable from the point of view of another time and place, not our own. Nevertheless, the characters live and breathe. The Count of Monte Cristo is not a perfect book, but its flaws are small, or else they are simply swept along by what is undeniably a great story. And that’s why you should read this book. It’s a book you can enjoy, and it will take you long enough that you begin to feel like the characters and story become a part of what you think about each day. You will have favourite characters and there will be others you dislike. And in the end, you will feel like you have read something entertaining and satisfying. What more can you ask from a novel?

RSS Feed

RSS Feed Facebook

Facebook Instagram

Instagram YouTube

YouTube Subscribe to our Newsletter

Subscribe to our Newsletter