The title is most intriguing: The Corner that Held Them; it’s what first drew me to this book. Being ‘held’ is not necessarily violent, but one connotation of the word implies restraint and control. And ‘corners’ can be places of shame or punishment: to be put in the corner. Remember Dirty Dancing?: “Nobody puts Baby in a corner.” The implications become more intriguing when you know just a little more about this book. It’s the story of nuns living in a convent in medieval Norfolk, from its founding in 1163, through the years of the Black Death in the 14th century, and just past the peasant revolt of 1381. This is an intelligent historical drama, full of ideas, which is also a compelling read.

Though nothing like it in style or purpose, the long timeline of the novel reminded me vaguely of Ken Follet’s The Pillars of the Earth. More accurately, parts of the novel reminded me of the psychological strain of William Golding’s The Spire. Follet’s novel is the story of building a cathedral while Golding’s focusses on the building of the titular church spire. Each represents more than religious devotion. And given its timeline, The Corner that Held Them is also a multigenerational tale. So while its story is therefore loosely structured around a few key characters, this is the story of the convent and the times in which it operates. In reading it we may question how our own humanity and freedoms are defined by the community in which we live.

The opening scene is immediate and gripping. Alianor de Retteville lies naked with her lover, Giles, when her husband, Brian de Retteville, armed, bursts in with his two cousins. He slays Giles in front of Alianor. Alianor, for her part, accepts she is about to be killed so she just lays there, her nakedness defiantly on display, which embarrasses the men out of their rage. They let her live. She lives another ten years, although we are never offered any further insight into what she thinks of her marriage, or how she feels bearing two more children for her husband before she dies in childbirth with a third. As is the way with human nature, Brian de Retteville surprises us by choosing to honour his wife with the establishment of a Benedictine priory with Alianor’s fortune, also contributing half his own fortune to this cause in his will, much to the chagrin of his two children.

We are only five pages in.

The narrative shifts to the priory: the story of its early prioresses, its financial woes, the dissatisfaction of peasants displaced from their land so the priory may be built, and the arrival of the Black Death. On a first reading, the first chapter may seem daunting; a reader may wonder where the story is heading or how many changes and characters will need to be accommodated by memory: floods, hornets’ nests, bestiality, the breaking of vows and the election of a new prioress all happen within half a page. A few particularly succinct lines skip us through 49 years:

In 1208 came the Interdict.

In 1223 lightning set fire to the granary.

In 1257 the old reed and timber cloisters fell to bits in a gale

But be patient. This novel is highly rewarding. It settles into a story and it is full of incident, intrigue, human folly, humour and insight. It may not have a single main character with a single story, or a traditionally structured plot, but it evokes a way of life and a period, and elicits questions about women’s autonomy, the place of religion, the exploitation of the poor, as well as our humanity and sense of purpose in life.

To begin with, it would be easy to read The Corner that Held Them as anti-religious, but I don’t think that does the book justice. The book is critical, but Sylvia Townsend Warner was intellectually complex and unconventional for her time. She was an active Communist Party member and lived many years with another woman, Valentine Ackland. They considered themselves married even though that was not officially available to them. They were anti-fascists and in 1936 the two women volunteered in a British medical unit in support of the Republican Army in Spain during the Spanish Civil War. Even so, Warner became a Catholic in 1952, four years after the publication of this novel. What reads as criticism of the church may also be read as a subtle engagement with doctrinal debate of the 14th century church.

The convent at Oby falls short of its religious ideals, beset as it is by debt, the social changes brought about by the Black Death, as well as the peccadilloes of its individual members. The convent has a religious mission, but it exists in a world in which finances are real, food must be grown, tradesmen must be paid and the convent must be organised. Each of the prioresses face these problems, including the silliness of some of the nuns. Salome breaks her leg when she becomes convinced she can fly (the television series The Flying Nun began in 1967) while Adela de Retterville, from the convent’s founding family, is sent to them as a novice without a dowry and possesses no common sense at all. And the patriarchal control of the bishop and the religious mission of the convent are ideological constraints which circumscribe their lives in ways they find hard to imagine or articulate: a box, if you will. But the convent’s day to day administration and mundane challenges are a box too, which limits the efficacy of their religious mission. Warner isn’t interested in lampooning religion. At times she is critical, but she is rather interested in the challenges of this time and the humanity of people living this life.

“For each one of us lives in a microcosm, the solidity of this world is a mere game of mirrors, there can be no absolute existence for what is apprehended differently by all.”

The Corner that Held Them, page 238

What we understand as readers – what the nuns fail to understand in their limited temporal sphere – is that the priory is out of touch with the changing realities of its world. The Black Death, having killed off a large proportion of the workforce, has changed the economic and social power of peasants, and is even breeding discontent among manor serfs. Sir Peter Crowe, the convent’s first priest, leaves the convent to replace the dead priest at Waxelby where lay people have begun to administer sacraments and hear confession. Sir Peter, at least, cynically understands the threat: “what can be more humbling than to know that the sacramental work is efficacious without regard of him who performs it?” The Black Death has left a hole in the clerical population (Philip Ziegler’s The Black Death, (1969) offers a very readable account of this period in which the clerical population died at a greater rate than any other section of the population). Sir Peter states the problem succinctly: “What is at stake is whether the Church is to keep her hold over the souls of her children.” The church is facing a crisis of purpose and relevance.

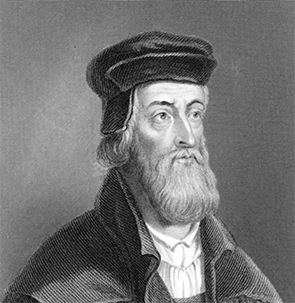

Sir Peter’s concerns are the closest any character comes in the novel to directly addressing the issue of Lollardism. The word was later coined in the 15th century as a derogatory term, but the tenets of Lollardism, a proto-Protestant movement led by John Wycliffe, began in the 14th century during the period covered by this novel. Wycliffe was a Catholic preacher who was dismissed from Oxford, during the year this novel ends, for criticising the Catholic Church. The Lollards famously advocated for a Bible in English, which would diminish the authority of priests to interpret it for the laity. But in their later petition to parliament in 1395 they reject the accumulation of wealth by church leaders, their involvement in secular matters, and supported the doctrine of universal priesthood, thereby questioning the special status conferred upon priests to hear confession. This is the historical context which is largely absent in the thinking of those in the priory: what Sir Peter is clearly concerned about.

The convent is a prime example of what the Lollards campaigned against. It is primarily consumed by profane concerns. Upon her election, Prioress Alicia’s all-consuming priority is to build a spire atop the convent’s church. On the face of it, it is an act that gives glory to God. But Alicia spends years organising funding and masons, never letting go her obsession, even throughout the period of the Black Death. She uncharitably anticipates the death of a nun whose passing will contribute money for the spire. Another young nun, Matilda, is highly popular and her success in the convent is anathema to Alicia, who irrationally sees Matilda as a rival to her languishing project. The spire becomes the measure of Alicia’s tenure as prioress rather than any spiritual or charitable work. And so it goes with the convent in general. Once the spire is finished, succeeding prioresses turn to other temporal concerns, like the perennial problem of debt, unpaid dowries and the politics of the church. One even covers up a murder.

What makes this novel cohesive isn’t a central protagonist. Instead, it coheres around key characters and a set of ideas. For example, apart from Alicia’s long prioress-ship, one of the main characters in the novel is Ralph Kelso, a false priest: ironically, given the opportunity afforded by the departure of Sir Peter Crowe who has left and the convent to defend England against Lollardism, Ralph is a character embodying Lollard principles. Ralph turns up at the convent one day during the period of the Black Death, looking for food. Without thinking why, Ralph claims to be a priest and accepts the vacant position. His presence creates tension in the plot: not just the ordinary tension of will or won’t he be exposed, but the implications about the state of the souls under his care who have relied upon his sacraments and guidance: “The absolutions were void, the rite was sacrilege. He was damning himself and abetting the damnation of others”. As readers, our attitude to this situation will no doubt be affected by personal belief, but Warner has contextualised it within its historical moment.

However, Ralph’s story does not stand alone and so it comes to mean more than the religious dilemma it raises. Warner parallels Ralph character with other characters. Jackie, for instance, is the son of Ursula, the convent’s cook. She is also a former nun who lapsed. Jackie’s illegitimacy means he can never be a priest, even though he will receive the education and possesses the intelligence that would make him fit for the role, like Ralph. Like other characters, Jackie’s life and opportunities are circumscribed by birth, wealth, church doctrine and tradition. Ralph’s position as the convent’s priest suggests Jackie’s lost potential. Instead, Jackie takes another path, leaving the convent, while Ralph remains for years, beginning to feel that he is wasting his life:

He had as much ability as other men, as much endurance, more health and strength than many. If he could get rid of his fat he would be in excellent condition. But his life had been aimless as an idiot’s, in his youth running from place to place with an idiot’s delight in motion, and now, like an idiot, set down in the chimney-corner.

The word ‘corner’ appears four times in the novel. Ralph’s ‘chimney-corner’ seems a bleak place of aimlessness and waste. Suddenly, we are wondering again about the title, except Warner has introduced the idea of ‘corners’ before this. During the period of Alicia’s spire, it begins to feel like a cursed project to her, while her bishop uncle loses his position over his dubious methods of providing funds for it. Alicia does not find solace in her religion, but feels imprisoned:

And here I am, she thought, fixed in the religious life like a candle on a spike. I consume, I burn away, always lighting the same corner, always beleaguered by the same shadows; and in the end I shall burn out and another candle will be fixed in my stead.

It is these perceptions, brilliantly realised in Alicia’s case by the metaphors of the candle and the corner, which suggest a cohesiveness through the novel’s insights, rather than through the traditional mode of character and plot. The nuns of the Oby convent seem too concerned with issues of the world to hold with our standard stereotypes of nuns. They rarely find purpose in religious observance, which seems unedifying and, at best, contrived. We see this in the self-deluding practices of various characters who struggle to transubstantiate religious faith into religious experience. For instance, Bishop Walter believes himself to be a man illuminated by visions, but his experiences seem somewhat tainted by the effort he undertakes to ‘enhance’ them:

Throughout his life Walter Dunford had availed himself of his naturally strong sense of the supernatural, and had been constantly assisted by visions and by voices, sometimes almost believing, and never quite disbelieving, and always convinced that even if he did a trifle enhance and exploit these adjuncts from another world it was by God’s will and for God’s purpose that he did so . . .

This willing self-delusion is practised by other characters, even Ralph. When Lilias reports that she has been visited by Saint Leonard and struck down by that saint in a vision, Ralph adopts a similar rationalisation. Suspecting that in reality another nun, Dorothy, has struck the saintly blow, Ralph reasons that,

. . . very probably Dame Dorothy’s soul had had its moment of necessity in striking that blow from behind. The blow was necessary if Dame Lilias was to be freed. Everything is planned by divine intelligence: a cipher is begotten and born . . .

In essence, religious or even miraculous occurrences are represented as God’s agency even when their provenance is self-serving or banal.

In fact, the only moments when characters approach a spiritual experience lies within the secular world, beyond the aegis of religion. The false priest, Ralph, would rather eat, conduct his relationship with the bailiff’s widow and go hawking. But it is his love of hawking which brings Ralph to his love of poetry, a vehicle for a kind of spiritual elevation. When he seeks a new hawk from the widow of Lord Brocton, Ralph is shown an epic poem written by Brocton, the ‘Lay of Mamillion’, which Ralph is asked to take and introduce to the world. As he reads it he is transfixed by the ordinary moments of life expressed in the poem which elevate his mind to numinous reveries. The convent, by contrast, merely sustains his earthly needs – he first came to the convent for food – but it offers nothing of spiritual satisfaction: “he found that he did not live by bread alone, and in a house that was a model of sober carnality he began to worship the spirit.”

Henry Yellowlees, appointed as custos to the convent by Bishop Walter, has a similar experience. Henry sees purpose and reason only in the works of man. In Nature, which should be a testament to God’s glory, Henry perceives only change, ruin and purposelessness:

The clouds were gone, only a few shadows were left, hastening to the northward. Brilliant, senseless, irresponsible, the landscape stretched before him. What soul was there, what trace of praise to its Maker? What trace of reason, what trace of purpose, except where man’s sad hand had etched it?

While travelling to Esselby to collect a rent debt for the convent Henry stays one night at a leper-house where the chaplain of lepers encourages him to sing a Kyrie with him. It is a new style of music in Henry’s experience and its beauty is a revelation. The Kyrie requires three voices and the chaplain calls a leper to join them. Although Henry is initially reticent in the leper’s presence, the beauty of the music they create together transports him: “Henry lay awake, recalling the music, humming it over again to the burden of the chaplain’s snores, with half of his mind in a rapture . . .” Later, it will be Henry’s knowledge of music, not his religious knowledge, that will earn him a promotion from a new bishop.

In addition to this, the only characters who gain insight beyond the tenets of Christianity are those who travel beyond the confines of the convent, whether it be Alicia who sees her new spire from a distance, Ralph who is introduced to poetry, Henry who finds music or Jackie who finds an entirely different life. Over and over the religious life as it was officially conceived in the 14th century is found to be limiting: nuns are distracted by mundane concerns, ambition or avarice. The power of the prioress is consumed by politics, the dictates of money or self-delusion. Implicit in this is the religious debate of that period of which the nuns seem unaware: Lollardism. After all, they are taken by surprise by the peasant revolt. There is a subtle distinction, then, between characters who travel and those who remain: of those who get to look outside the box and those who don’t. Hermione Hoby stated in a Harper’s Magazine article:

The book has no ending; it just ends. An equally conclusive ending could be found by closing your eyes, riffling back any number of pages, and designating a spot with your finger. Just as death so often does, the end comes abruptly, without fanfare.

I couldn’t more disagree more. The novel ends at a point of conflict, a misunderstanding and a twist. Everything that has happened converges upon a fateful decision. Lilias believes she has been struck by Saint Leonard. As a result of this encounter she desires to be an anchoress, yet her decision has been frustrated by the bishop for years. The question of whether she and her travelling companion learn anything, makes the story of this seemingly minor character central to the novel.

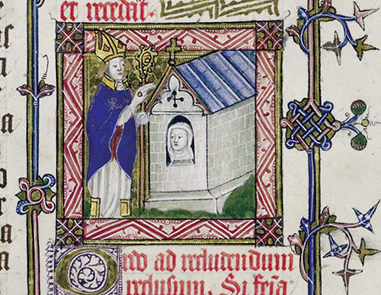

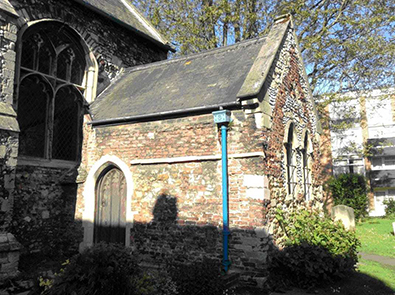

In 1534 the English parliament passed the Act of Supremacy, which cut England’s ties with the Roman Catholic Church and made Henry VIII the supreme head of the English church. In 1536 he began one of the most significant religious and social changes in English history by dissolving the monasteries, including priories, convents, and friaries. As a result, Anchorites, who were considered by many to be central to religious and community identity, no longer had a role to play. Anchorites were usually attached to a church or convent, and lived in cells where they could focus upon a spiritual life. Nuns or priests who wished to become anchorites had to be granted permission by a bishop. A ceremony was held, much like a funeral, which effectively made them dead to the material world and gave them saintly status. They would usually live in their cells the rest of their lives.

In essence, to be an anchorite is to accept voluntary imprisonment, whatever arguments may be made for the spiritual life and its benefits. This is what Lilias seeks and what Sibilla, who is the niece of the bishop who denies Lilias, feels she must help her achieve. As readers, we are positioned to ask ourselves whether this kind of life is a free choice within the bounds of patriarchal religion – far more women chose to become anchorites than men – or whether it is another corner: the ultimate corner to back oneself into.

The Corner that Held Them is highly original and well written. Despite some claims that the book does not have a plot, this is not true. If you are of a mind to prefer books with main characters then Prioress Alicia can keep you company for at least half the book, while the false priest, Ralph, will see you almost to the very end. But by that time you won’t care who is and who is not currently in the action. By that point you’ve come to know everyone – no character is inconsequential – and you are likely to love this novel’s thought-provoking ending as much as I did.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed Facebook

Facebook Instagram

Instagram YouTube

YouTube Subscribe to our Newsletter

Subscribe to our Newsletter