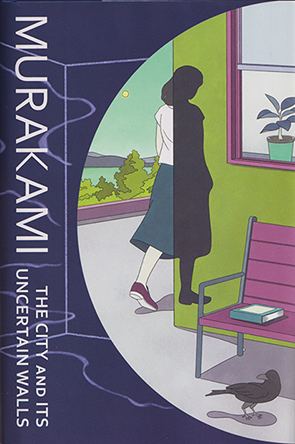

The City and its Uncertain Walls (CUW) is a peculiar work. It’s a rewriting of a novella Murakami published in 1980 which he says he was unsatisfied with, but in this new version he has expanded it to include two parallel stories featuring a mysterious walled town the protagonist enters as well as a town he works in as a chief librarian. Like other works by Murakami, it posits an alternative world. In 1Q84, Aomame enters an alternative version of the year 1984 after she leaves a highway via an emergency stairway. We always know when Aomame is in this alternative world because there are two moons there. In The Wind-Up Bird Chronicles Toru enters wells which represent his subconscious or unconscious state, and an alternative reality. Protagonists in Murakami’s novels often find a means to enter an alternative world where they must confront issues about their lives. In CUW Murakami’s unnamed narrator enters a mysterious town surrounded by a wall. The narrator and his unnamed sweetheart from the first part of the book have imagined the town into existence during the early days of their innocent romance. The girl tells the narrator that she is not her real self, merely a “stand-in” or “wandering shadow” of her real self who exists in this town. To enter the town, she tells him, people must separate from their shadows, and they are prevented from leaving the town by a vigilant gatekeeper. The narrator finds his former sweetheart when he finally enters the town, although her ‘real’ self doesn’t know him because he has fallen in love with her shadow in the outside world. She assists him in his job as the town Dream Reader. The town’s library has no books, only dreams encapsulated in eggs, held on the library shelves. The role of the Dream Reader is never definitively defined, but it is a role essential to the town’s existence. Around the town, unicorns wander, suffering and dying from the terrible cold of winter, while in spring the survivors engage in vicious battles for the right to mate. Time seems arrested or of no consequence. The only clock in the town has no hands to show the time.

This is the world of Murakami’s walled town. Perhaps it is of note (because Murakami writes about it in his afterward and continues to discuss it in interviews about the novel) that this book was largely written during the Covid lockdown. Murakami writes in his afterword:

I started writing this novel in March 2020, just after the coronavirus began its rampage across Japan, and finished it nearly three years later. In the interim I rarely set foot outside my home, and avoided any lengthy trips, and in that weird and tension-inducing situation … I worked steadily, day after day, on this novel (like the Dream Reader reading old dreams in the library)

At one point, as the narrator tries to make sense of the town, he is told that the purpose of the isolated town and its impregnable wall is “To prevent an epidemic”. Further to this, he is told that this is “epidemic as metaphor”, and that what is really being guarded against is an “epidemic of the soul”. This is not to attempt to explain Murakami’s work as a simple metaphor where a=b. This is not a simple story about lockdown, and I think we can only take Murakami’s comments as an insight into the creative process; the way the real world, itself, can impinge upon the imagination.

But that may also be the point. The world imagined by the girl and the narrator becomes real enough that other characters are aware of it and wish to go there. The circumstances of their meeting – each a finalist of an essay competition – and their immature sexuality (aged sixteen and seventeen at the time they meet) may be displaced in this wall-off version of themselves. That’s one interpretation, but it would be easily displaced by any number of interpretations that others will bring to the problem of the town and its wall. After all, Murakami, himself, is somewhat circumspect when it comes to discussing his work. Of the Covid situation, he goes on to say in his afterword, “Those circumstances might be significant. Or maybe not.” But the comparison does speak to the idea of an inner life or identities we hide from the world: that the world of our imagination, may be more real than the self we are forced to present to the world, acknowledging that our public identities necessarily come with their own walls and defences. The girl tells the narrator that he can only enter the town if he can find it, and he understands that she also implicitly means “As long as you are seeking the real me.”

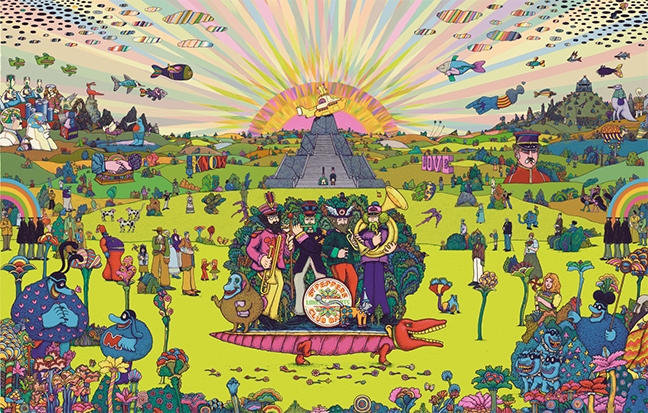

It is this kind of equivocal storytelling that may either frustrate or liberate readers. Those who desire explanation and certitude may find the book difficult, since Murakami’s story never consistently explains its meaning. Throughout the novel it is emphasised that what happens in dreams is more important than real life. Yet there is an indistinct line between dreams and reality. Can we really know what reality is? Does it matter whether we are the ‘real’ identity we assume or our ‘shadow’? All this incertitude is manifested in different ways. Memory is a product of a certain amount of truth but also of fiction and is therefore not entirely reliable. Then there is the matter of facts, like the boy, M★★ who is able to immediately tell someone the day of the week they were born based on their date of birth, and who remembers verbatim the many books he reads in the library each day (the library that sits on the ‘reality’ side of the narrator’s story). But facts are not everything; they don’t explain everything. Because along with the talents of this peculiar boy is his deep need to find the hidden town where his authentic self will find a purpose in the world. M★★ is strongly associated with The Beatles film, Yellow Submarine, by the T-shirt he constantly wears, and the film’s polymath, Jeremy Hillary Boob PhD, who is able to ravel off a multitude of facts in rhyme. Facts are M★★’s life, but there is also a deeper truth they do not explain. Between the ‘real’ town the narrator moves to, to take up his position as a head librarian, and the ‘unreal’ walled town where the library contains only dreams, it seems reality is something we choose rather than merely inhabit passively. For readers willing to speculate, Murakami’s inconclusiveness is liberating. It can be whatever the reader desires or needs it to be.

For Murakami, specifics are always deferred or avoided. M★★’s association with Yellow Submarine calls to mind the utopian dream represented by Pepperland which is invaded by the Blue Meanies, which therefore somewhat characterises our notion of an alternative reality. But the walled town does not possess the psychedelic perfection of The Beatles’ film, nor is it utopian in any manner. Though created through an act of imagination, houses sit derelict and empty in the town. The town is divided into districts representing class divisions, suffering and death continue and the townspeople are controlled by the gatekeeper as well as stories that discourage them from leaving.

But Murakami is capable of shifting gears and making different cultural associations, too. For instance, Japanese readers will no doubt readily make associations between this story and Japanese folklore from Shintoism. When the boy disappears into the walled town, his father and brothers come to speak to the narrator, hoping to find clues as to his fate. They express a belief that he has been “spirited away” enough times that even English readers can make a connection with Hayao Miyazaki’s 2001 animated film Spirited Away, in which ten-year-old Chihiro Ogino disappears into an alternative world after she and her parents pass through a tunnel into an amusement park. ‘Kamkakushi’, meaning the act of being spirited away and hidden by the gods, is the concept at the heart of Miyazaki’s film, based upon the Japanese Shinto religion. Traditionally, families might explain the disappearance of a loved one in this way.

So, Murakami’s tale draws upon Western and Japanese culture, and the story is vague enough that it might mean many things to many people. But there are also enough clues in the narrative to make us think that the walled city is a representation of the inner self, the imagination or the unconscious state. When the narrator tries to map the town, the walls seem to move and appear sentient. Time passes in the walled town, but paradoxically it does not. Days turn to night and then become day again, but time does not seem to progress. Age is arrested. Time is like the ocean, ever changing yet always the same, or it is stopped, or it is a representation of a perfect moment, or it has no meaning. Like a mind, the city is free of the time that it inhabits. It is created through an act of the imagination and it remains elusive as a dream or Shangri-la.

Shadows are explained in the same inconclusive manner. Discarded when one enters the town – like Peter Pan losing his shadow – shadows seem to exist in the outside world as a real but alternative version of the self, like two halves of one identity. They are also likened to the soul, which extends the metaphor of the town beyond imagination or the unconscious to also inhabit the realm of death. This is the purview of ghosts, but it is also a representation of what we may again refer to as a ‘soul’. Mr Koyasu, the former librarian of the ‘real’ town, exists in a state between life and death, and is therefore able to intuit that the narrator has once before lost his shadow. Over and over, no matter how we choose to understand this story, we are presented with the possibility that existence and reality extend beyond the physical and rational limits dictated by jobs and the quotidian existence of our lives: whether that be in a realm beyond life, beyond consciousness or ordinary reality.

I have not read Murakami’s original version of this story from 1980, but it seems reasonable to assume this rewritten version is an improvement. The atmosphere of mystery is heightened because he is able to establish the tenets of the walled town, but then preserve its mysterious, illusive reality at one remove, by parallelling aspects of that town and the narrator’s situation there with the town he moves to for his new position. In both towns his job is in a library in which he does not fully understand his role. In both towns he is largely isolated from the politics and culture of the town, itself. Then there is the boy, M★★, he meets and mentors in the town who is “sixteen or seventeen”, roughly the same age as the narrator when we first meet him. M★★ is a representation of a facet of the narrator’s own identity, a fact made clear during the course of the plot. And in the second ‘real’ town the narrator also finds romance with a woman who owns a coffee shop. Though it is a more mature desire he feels for her, the result is the same: she is psychologically incapable of participating in sex.

Murakami states in his afterword that he originally intended this kind of alternating parallel stories for his rewrite, and that eventually “the two would combine into one.” While this is a strength of the novel, its one flaw is the book’s repetitions: not narrative parallels or allusions, but constant simple repetitions of information or facts about the walled town, or what people have said or done, as though Murakami has not been confident in his reader. Or that in rewriting the story he maintains a certain level of insecurity or doubt about its premise. It’s a small criticism, but it’s an aspect of the novel which is sometimes jarring.

Even so, this is a well-controlled and fascinating story in which the author requires us to suspend our disbelief and to enter his world. There are many facets of the story that are simply not desirable to discuss here: that should be left to a reading of the novel, itself. Because the story is an immersive experience: something to ponder. This is a novel that works best when it engenders reflection; about life and our existence, perhaps. But really, it could mean whatever a reader brings to it.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed Facebook

Facebook Instagram

Instagram YouTube

YouTube Subscribe to our Newsletter

Subscribe to our Newsletter

No one has commented yet. Be the first!