For many years, The Canterbury Tales was something mythical to me. The most well-known and persistent work of Chaucer — himself a seemingly legendary figure — and yet, it was a piece that I’d never known anybody to read. I certainly didn’t know even one person who could identify a single tale from this collection.

I eventually found out who reads Chaucer: college students taking Introduction to English Literature courses. That was where I was assigned to read The Tales, or at least three of the most-beloved (specifically, ‘The Knight’s Tale’, ‘The Miller’s Tale’, and ‘The Wife of Bath’s Tale’). And I finally understood the hype. I told myself, one day, I will go back and read the rest. It took a few years, but I finally did.

Let me be clear up front, this is an unfinished work. Chaucer really bit off more than he could chew; his intention was that the pilgrims traveling to and from Canterbury would tell four stories apiece. As it stands, not all of them even got a first go-around. Two or three tales are not fully finished, and not even the cast of characters is consistent the whole way through. Fortunately, as this is an anthology of sorts, each tale is able to stand on its own, and no aspect of its incompleteness is egregious enough to prevent casual enjoyment.

I’ve hinted at this already, but one of the best elements of The Canterbury Tales is its framing device. A party of assorted travelers tell stories to pass the time on their journey to Canterbury; the nature of these tales tend to be appropriate to the character telling them, and the travelers often banter with each other between stories as their personalities clash. In these moments, you can clearly see Chaucer’s sense of humor peeking through, which I think is what I love most. Not only does he go so far as to insert himself into the scene as one of the travelers, he sells you on the idea that he's simply recording the stories told by the others, because his own tales are far worse by comparison. Heck, his first tale is so bad that he’s asked to stop partway through and tell another. The overall tone is very tongue-in-cheek, and entirely unlike what you would expect from “classic” (read: “serious”) literature. Chaucer knows you're in on the joke.

The tales themselves are . . . quite a mixed bag, both in terms of tone and quality. Describing the tone of The Canterbury Tales, I once quipped that with Chaucer, it was always “either child death or fart jokes, with no in-between.” This may be a bit unfair, but not entirely undeserved. With few exceptions, it would be quite easy to split these tales into two categories:

- Stories about virtuous figures who prove their devotion to God and/or church doctrine, often through hardships borne from completely implausible events

- Farces wherein an unsuspecting character is made a fool of, often via a series of completely implausible events

Despite the clear divide, the presence of the travelers as an interlude between stories is used to great effect, preventing the fatigue of tonal whiplash.

As to quality, I think you experience the greatest highs and lows within the first three tales. The book opens with two of the best: one, ‘The Knight’s Tale’, is an action-filled epic based around a love triangle that’s seemingly impossible to resolve; the other, ‘The Miller’s Tale’, is a narrative so unexpectedly raunchy and hilarious that it persisted through all attempts to censor it. However, this high comes crashing down in the third tale, which decides, in trying to emulate its bawdy predecessor, to play sexual abuse for laughs. Perhaps this was still seen as a fun prank in Chaucer’s time, but it hits much differently now, and it clearly exemplifies just how much this society hated women. Naturally, if a woman is present in a tale, she’s there to be won by the protagonist (although curiously, in most cases, the woman is the wife of another man). If the woman is the protagonist herself, then she is always the most dutiful and mild-mannered of women, because she is an example to be followed. Even the tale told by the Wife of Bath—who would consider herself a proud feminist in the modern day—is extremely problematic in how it presents the idea that a man can unlock the “best” version of a woman simply by selecting all the correct dialogue options.

Ranting about societal norms aside, the tales also occasionally suffer from the pacing issues typically experienced in older literature. Much of the time, this occurs when one of the travelers—very often (but not always!) those affiliated with the Catholic church—goes off-script and very needlessly expounds on their beliefs. That said, I found that, of the tales themselves, only two were difficult reads. One of these is told by Chaucer himself; again, a funny joke that he is a poor storyteller, albeit one that goes on far longer than is amusing. The second is the closing tale, which is less of a story and more of a sermon. Understandably, it is very dry; it also has the distinction of being the longest of the tales, making it a very unfortunate ending note. Although it is hard to blame Chaucer for this, because again, the parts that were finished were only supposed to represent Day 1 of 4.

I’ve provided a lot of caveats one should be aware of before you dive into The Canterbury Tales; still, I think this is definitely worth a look, even if you don’t intend to consume it in its entirety. Make no mistake: in most cases, this is an absolute blast to read. For one, 95% of the work is written in jaunty rhyme (which in and of itself is impressive; I can’t vouch for how many of these tales were Chaucer originals, but certainly this was likely the first time many of them were put to paper). But on top of that, when you think Canterbury Tales, you imagine the finest, high-class parables; and that’s not what you get. What you get is toilet humor, and love and loss, and drunken shenanigans, and religious martyrdom, and quite a lot of sex. In other words, it’s incredibly human; and to me, it’s the most connected I’ve ever felt to people long-gone, who felt the same feelings and faced the same problems that we still struggle with to this day, and likely always will.

The Canterbury Pilgrims - North Reading Room, Library of Congress

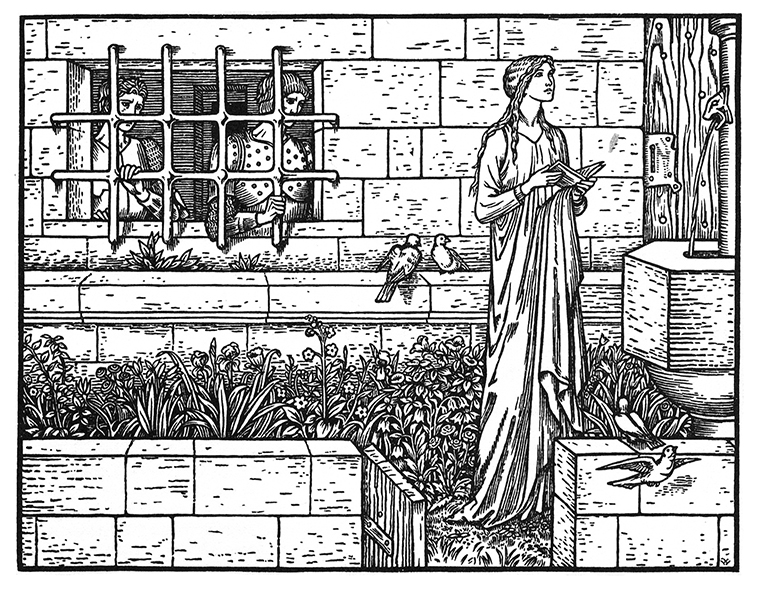

The two images below depict the pilgrims on their way to Canterbury to visit the shrine of St Thomas Becket. Chaucer uses the pilgrims journey to Canterbury as a framing device for his work. Each pilgrim is meant to tell stories to pass the time.

Highsmith, Carol M, photographer. North Reading Room, west wall. Mural by Ezra Winter illustrating the characters in the Canterbury Tales by Geoffrey Chaucer. Library of Congress John Adams Building, Washington, D.C. , 2007. Photograph. https://www.loc.gov/item/2007687162/.

LEFT TO RIGHT: The Miller, in the lead, piping the band out of Southwark; the Host of Tabard Inn; the Knight, followed by his son, the young Squire, on a white palfrey; a Yeoman; the Doctor of Physic; Chaucer, riding with his back to the observer, as he talks to the Lawyer; the Clerk of Oxenford, reading his beloved classics; the Manciple; the Sailor; the Prioress; the Nun; and three priests.

Library of Congress, North Reading Room, east wall. Detail of mural by Ezra Winter illustrating the characters in the Canterbury Tales by Geoffrey Chaucer

LEFT TO RIGHT: The Merchant, with his Flemish beaver hat and forked beard; the Friar; the Monk; the Franklin; the Wife of Bath; the Parson and his brother the Ploughman, riding side by side

A Related Book

RSS Feed

RSS Feed Facebook

Facebook Instagram

Instagram YouTube

YouTube Subscribe to our Newsletter

Subscribe to our Newsletter

No one has commented yet. Be the first!