Way back, about a hundred thousand years ago, I read this book when I was in primary school. I borrowed it from the school library, as far as I know, because I’ve never owned a copy until now (even from a young age I tended to own rather than borrow books). It’s one of the few books from my childhood that really stuck in my head. I think any author would be happy to occupy their reader’s headspace for nearly fifty years (as a more realistic estimation of the timeline would allow). A few months ago I remembered the book when I had the idea to start a vegetable garden, and I ordered it.

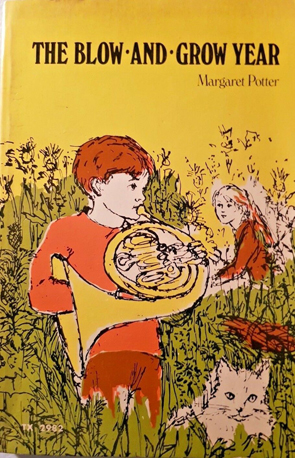

First, here’s what I thought I remembered about the book and why it stuck in my head. I had memories of a family in a large house. One of the children was learning to play a French horn (this detail is helped by my very specific memory of the cover), while another cleared some overgrown ground and grew vegetables. It probably doesn’t sound like an exciting premise for a children’s story, but it made an impression on me that was in some way profound. The children had recently lost their father, a detail that resonated for me, and I understood that their experiences in the year after they move into the new house with their mother healed them. That was my understanding, although it is never explicit in the book. There was something that appealed to me strongly, about the vegetable patch, the hard work, and the way the main character, Jocelyn, grew and changed along with her garden. Whoever thinks kids don’t get things from books – don’t understand anything more profound than what happens at a surface level – is wrong. The vague memory of the story left me with a longing to make things, specifically to grow things I might eat. But a teaching career, family, renovations and life in general have pushed the aspiration further and further into the future.

Until I bought some wood a few weeks ago to put some raised garden beds together.

But to get back to the book . . .

The Blow-and-Grow Year was the second novel Margaret Potter wrote about Jonathan, Jocelyn (the names of Potter’s own children) and their brother James, known as Podge. It followed The Touch-and-Go Year. I never read that book, but a quick read of a summary reveals that it tells the story alluded to at the beginning of this book. The children’s mother, Mrs Sinclair, has recently been widowed, and the children are sent to live with an aunt and uncle while their mother trains to be a teacher. The Blow-and-Grow Year tells their story after that. Mrs Sinclair has her first teaching appointment and the family move to the country where they occupy a large old house that still has possessions from its previous owner, an old lady who has died. A grand piano sits in the house, still, too large to remove after a long-ago extension, and Podge finds a French horn which he immediately takes to, teaching himself to blow it, and even ringing a musician for advice. Jocelyn, is drawn to the piano. She has previously had lessons, but her mother ended them when Jocelyn failed to ever practice. Now older, Jocelyn believes she will be more committed, but her mother is not convinced, and says that Jocelyn must earn the money if she wants to learn again.

This is where The Blow-and-Grow Year would have been the same as any other book for my younger self. There are definite ‘themes’ that tie the plot together. Jocelyn needs to learn personal responsibility and to be less impulsive. She will have to decide whether her desire to return to the piano is sincere, or a whim. And the means by which she tries to earn the money sets her to some hard work: she starts to clear the enclosed garden, overrun by weeds, and meanwhile sells thistles and other plants she picks to flower arrangers at a local market.

But there are deeper needs expressed in this book, also. Podge is happy with his French horn and plays for hours alone. Jonathan makes friends with some neighbouring children who are eager to play tennis with him. But Jocelyn is alone in this new house. The Eltons are an old couple who live in a neighbouring property. There is no-one nearby who is a suitable friend. It isn’t until Sammy and his daughter, Vanessa, arrive in their caravan, that Jocelyn has a hope of making a friend. But complicating that is the growing suspicion that Sammy might be involved in something nefarious: the theft of valuable art sought by the police.

I had no memory of this aspect of the story. It’s a tried and true formula: the child protagonists solve the mystery and capture the bad guys when the police fail to do so. It is, apparently, also a feature of the first book, The Touch-and-Go Year (they prevent a burglary). It certainly provides for an exciting ending, and our child heroes are able to prove their growing independence and nerve. The outcome of the criminal plot also has an effect on the decisions Jocelyn will have to make about piano lessons (there was a reward for the stolen art, after all).

As I read, I was surprised that the garden did not loom as large in the plot as it did in my memory. It’s there at the end, like a desire fulfilled, while the garden is mostly a problem and a slowly emerging interest for Jocelyn before that.

Even so, I could see why this book appealed to me so much as I reread it, even though aspects of the plot I’d forgotten filled up space that was occupied by my memory, even though the book slipped into some fairly clichéd criminal action, and what I wanted most to hear – that everything would be okay and that time would heal – was never specifically said. But it was there in the blowing of the French horn and the growing of that ordinary vegetable garden. There are implicit messages children take from books, too: that being occupied, having a project, learning new things and being stimulated by new people, can heal too. I think this is a skilfully executed story that manages to convey these insights, even to a child, without ever clumsily saying them.

Another thing, too, is the book’s depiction of childhood, which is so different to the childhood of children now. The children in this book learn musical instruments, read, make a garden, sell their wares at the local market, explore, play tennis and hang out with friends. Many modern books tend to reflect the known world that children experience back at them. If you would like your child to experience a novel from a world before personal computers, this might also be an appealing aspect.

If you’re interested in this book, you are unlikely to find it in any bookstore. The copy I bought was published in 1970 and it originally came from a Middle School library in Massachusetts. You will have to buy it online if you’re interested, or find an old copy in a library. Luckily, the copies I’ve seen available online are not expensive.

I really enjoyed reading this again. It still appeals to the child in me.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed Facebook

Facebook Instagram

Instagram YouTube

YouTube Subscribe to our Newsletter

Subscribe to our Newsletter