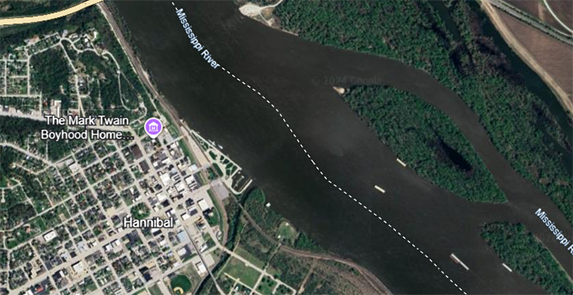

The world of St Petersburg, the fictional town where The Adventures of Tom Sawyer takes place, is based on the town of Hannibal, Missouri, where Samuel Clemens grew up, as well as the childhood experiences of Clemens’ and his friends. Of course, Samuel Clemens is better known as Mark Twain, a nom de plume drawn from his time as a river boat pilot, meaning to mark the depth of a river at two fathoms from a line. Twain’s experiences on the Mississippi River would inform his fiction, both in this first novel and more significantly in its sequel, The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn. If you haven’t been to Hannibal – I have not – a quick check of Google Earth will show you just how close Twain’s house was to the Mississippi River, as well as the islands which were presumably the inspiration for Jackson’s Island – Shuck Island and Pearl Island – where Tom, Huck and Joe Harper go to play at being pirates. That’s part of the appeal of this story: it is primarily a childhood adventure often based around childhood beliefs and imagination, but there is a basis in reality, too. And in telling the story of childhood, there is a feeling that Twain is also telling America the story of itself.

Twain’s two most famous novels have become iconic for this reason, not just in America, but in world culture. They are not just representations of childhood in the period, but a certain vision of America emerging in the 19th century. Tom Sawyer is about childhood lived within the dark threshold of an adult world. Huckleberry Finn, generally considered a more mature and accomplished book, enters that darker world more completely by acknowledging the issues of slavery and race in America. There are allusions in Tom Sawyer to the wider realities of slavery and racism, but it mostly skirts around these issues and focusses on the world of Tom Sawyer and his friends, predicated upon childhood imagination and superstition. Jim, a black slave boy, is barely mentioned. He undergoes a transformation in Huckleberry Finn, reimagined as an adult slave belonging to Miss Watson, Widow Douglas’ sister. This is largely why I’m rereading these books. Recently, Percival Everett has appropriated the plot of Huckleberry Finn in his novel, James, to tell the story from Jim’s point of view. I assume Everett had been drawn to Twain’s novel because it is a part of the fabric of American identity – at least that’s how I’m reading Tom Sawyer after returning to it for the first time since I read it as a child – and that the story of an American identity has been problematised by identity politics during the divisive Trump years. So rereading Tom Sawyer and Huckleberry Finn, it seems to me, is a sensible way to approach Everett’s novel and what it has to say, as well.

Before I talk any more about Tom Sawyer, though, I thought it was interesting to point out that Twain actually wrote four completed novels featuring these two characters. A fifth book, Huck Finn and Tom Sawyer Among the Indians and Other Unfinished Stories, is a series of stories written between 1868 and 1902, which, as the title says, are incomplete. After The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn, published in 1884, Twain published a third book, Tom Sawyer Abroad in 1894. In it, Tom and Huck travel to Africa in a hot air balloon (Jules Verne’s influence by this time is evident), while in the fourth book, Tom Sawyer, Detective, published in 1896, Tom and Huck try to solve a murder. Twain was evidently responding to the burgeoning popularity of crime fiction at that time, which suggests that he was an author sensitive to the zeitgeist. For fans of Stephen Norrington’s 2003 film, The League of Extraordinary Gentlemen, Tom’s stint as a detective may make some sense of Tom Sawyer’s character in that film, in which he appears as a US Secret Service agent who joins the rather eclectic League, which is comprised entirely of 19th century fictional characters.

My returning to read Tom Sawyer was something of a personal experience for me. There are scenes in the novel which had become formative since I read the book as a child. The death of Injun Joe, particularly. I remember going on a cave tour with my parents when I was quite young. I remember the fear – possibly instilled by the warning of our guide – that I could get separated and lost in the cave system. So, when I later read Twain’s novel, I think Injun Joe’s death touched something which was already fundamental in my imagination, and never left me when I took up speleology in my thirties. Now, the overall appeal of the book for me as a reader hoping to be entertained, lies in its representation of childhood; that Tom’s character speaks to childhood experiences that seem distantly familiar or at least desirable. He is brave, resourceful, funny and smart. He has adventures. He creates his own world imaginatively.

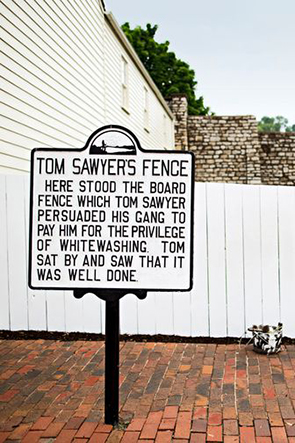

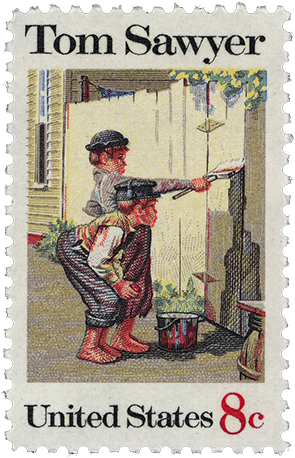

And Tom is a likeable rogue, but he is not malicious. He may trick his friends into whitewashing the fence for him, or he may falsely take credit in Sunday school by buying up the tickets from all the other kids to be awarded a new Bible. But he is also willing to take the blame for Becky Thatcher in school, and he refuses to accept his aunt’s and the town’s prejudice against Huckleberry Finn, whose father is an absent drunkard in the narrative. Tom’s adventures represent a kind of childhood that is now hard to access; one of innocence and a belief in a world transformed by imagination. Tom and Joe Harper re-enact scenes from Robin Hood. They play at being pirates and Indians. Tom and Huck go digging for treasure with nothing to guide their quest but superstitious and romantic stories about bandits and highwaymen. There is something distinctly quixotic about their endeavours.

But I think Twain is offering more than just nostalgic sentiment. First, the boys’ adventures have real world consequences, too. Their fantasies butt against the real-world machinations of the villainous Injun Joe. While Tom and Huck’s search for treasure in random places, even a haunted house, may seem naïve, it results in their actual imperilment as they are seduced by the thought of Injun Joe’s actual treasure. And while Tom may sulkily muse that his own death – preferably temporary – would teach his Aunt Polly and others his true worth, his fantasy is realised when their innocent desire to escape adult control on Jackson’s Island results in their purported deaths; even their funeral.

Throughout the novel there is a nebulous line between the imaginative world of childhood and the real world. The imaginative world of Tom Sawyer, Huckleberry Finn and Joe Harper, it is shown, is not so distant from the world in which adult aspirations find a parallel. In some scenes, Twain shows us that adults are sometimes similar to children. When Tom describes a dream to Aunt Polly in which he seems to have had a miraculous insight into a private scene, she is immediately inclined to believe his lie. Adults, like the children, exist in a world of religion and superstition. Despite Tom’s half-brother’s scepticism, Aunt Polly believes his lie because it accesses a set of religious and superstitious beliefs upon which Aunt Polly shapes her understanding of the world. And we may laugh at Tom’s awkward attempts to attract Becky Thatcher by showing off – tumbling and fighting and being silly – but we understand that Tom’s actions are prologue to adulthood, and that his melancholy, when he falls out with Becky, is just as real as any jilted lover’s.

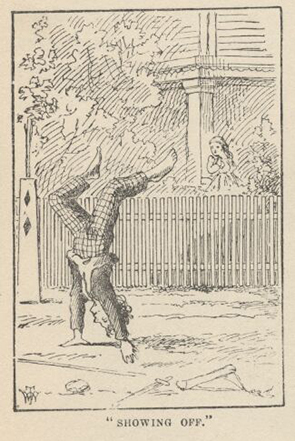

Because we know that Mark Twain wrote a famous sequel to this novel, it is easy to see Tom’s novel as a more innocent text that anticipates a darker reality. But this adult world is evident within this novel, already. Tom’s childishness is aped by adults for a start. When he sits in church, bored, he plays with a beetle, which also attracts the attention of bored adults sitting in the pews. When he sees Becky Thatcher – a girl whom he has been instantly attracted to but does not know – turn up in Sunday School, he immediately starts to show off to get her attention: “cuffing boys, pulling hair, making faces, in a word, using every art that seemed likely to fascinate a girl, and win her applause.” Tom’s actions seem ridiculous, but Twain offers them within the context of an adult world of individuals seeking attention for their own reasons. With the newly arrived Judge Thatcher present, the adults ‘show off’ with the same enthusiasm that Tom and other children are prone to:

Mr. Walters fell to “showing off,” with all sorts of official bustlings and activities, giving orders, delivering judgments, discharging directions here, there, everywhere that he could find a target. The librarian “showed off”—running hither and thither with his arms full of books and making a deal of the splutter and fuss that insect authority delights in. The young lady teachers “showed off”—bending sweetly over pupils that were lately being boxed, lifting pretty warning fingers at bad little boys and patting good ones lovingly. The young gentlemen teachers “showed off” with small scoldings and other little displays of authority and fine attention to discipline—and most of the teachers, of both sexes, found business up at the library, by the pulpit; and it was business that frequently had to be done over again two or three times (with much seeming vexation). The little girls “showed off” in various ways, and the little boys “showed off” with such diligence that the air was thick with paper wads and the murmur of scufflings. And above it all the great man sat and beamed a majestic judicial smile upon all the house, and warmed himself in the sun of his own grandeur—for he was “showing off,” too.

The parallels between Tom and Injun Joe also seem significant. They cross paths several times quite by accident: at the cemetery at night, at the haunted house and in the cave. But what brings their stories together goes beyond chance or the murder that Huck and Tom witness. Injun Joe essentially has the same aspiration as Tom: to become rich. And in attempting to hide his own treasure he finds another, altogether larger treasure, left by a former gang. What separates Tom and Injun Joe is Joe’s level of malevolence. Injun Joe is inexplicitly bad with no redeeming qualities, and it is here the novel raises the issue of Injun Joe’s race without addressing the presumptions of racism. He is an Indian. The Welshman, Mr Jones, a man Huck seeks help from, says that Indians typically notch ears and slit noses; an inhumanity presumably below the morality of white man. In short, Injun Joe seems less than human. So, the terrible fate that Injun Joe suffers is merely a curiosity – the place of his death becomes a site for tourists – and we would be encouraged to feel nothing for him except that we understand Tom and Becky have very nearly suffered the same fate. Injun Joe may be dismissed as an Indian by Mr Jones, but there is an uncomfortable association between Tom and Injun Joe, too. It’s an aspect of Tom’s characterisation that the novel never appropriately addresses.

Even so, Tom’s adventures seem innocent and they have a nostalgic appeal. But I doubt the novel would not have gained its place in American culture if this was all. I think part of its enduring appeal, beyond the story-telling pleasure of a childish picaresque adventure, is its representation of the American character. America had fought a war against the British for its independence, with a second major conflict in 1812. This is central to America’s sense of its place in the world and the idea of American exceptionalism. The American character was defined against the old world of Britain, but in the course of the century after its Independence it was also being defined through its intellectual culture. The French writer, Alexis de Tocqueville, attempted to define the character of America’s democracy in his 1835 book, Democracy in America. Individualism was one of the key values Tocqueville identified in the American character. Walt Whitman’s Song of Myself posited his own individuality as both unique and a part of a greater American enterprise. Lin-Manuel Miranda’s musical, Hamilton, is based on the same premise: the rise of an exceptional individual who comes to represent American Exceptionalism. Likewise, Tom Sawyer is not just a picaresque entertainment. Tom Sawyer is an American type.

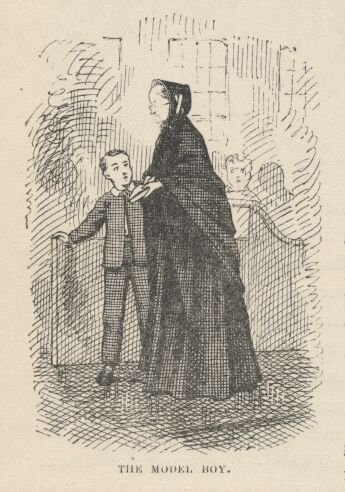

The idea of what America was and what it wasn’t is of importance. America defined itself against the rigidities of the British model – class, monarchy, tradition – while its society sought to reward ingenuity and the individual. The idea that Tom is an American type may seem axiomatic to anyone who thinks about it. But I think Lee Clark Mitchell’s introduction to the Oxford World Classics edition of the novel helps make the idea clearer. Mitchell explains that Twain also wrote Tom Sawyer in reaction to a form of fiction that had become popular, particularly in England: model-boy literature. This was literature written for boys which sought to instil appropriate values in its audience. The genre was particularly entrenched in English culture where this kind of writing reinforced notions of class and empire, and moral precepts were expounded through the agency of a model character. English writers like Robert Ballantyne and William Kingston were representative of a ‘wholesome’ literature that supported the ideals of empire and God, while more sensational stories, published in magazines that came to be pejoratively called Penny Dreadfuls, focussed on adventure without the attendant ‘appropriate’ ideals. As an example, Ballantyne’s novel The Coral Island, published in 1857, is about three boys marooned on an island in the South Pacific. The story expounds the civilising force of Christianity, implicitly upholds the ideal of the British class system, as well as the value of British imperialism. William Golding’s response to Ballantyne’s book was The Lord of the Flies, published in 1954. A group of boys are marooned on an island during a war. While they make efforts to organise themselves into a viable community, their group becomes fractured and they regress to brutal savagery.

Twain explicitly references the Model-Boy as an example of what Tom is not. Tom is popular in the village, but “He was not the Model Boy of the village. He knew the model boy well enough – and loathed him.” Later, as the villagers gather to enter church for a Sunday service, Twain’s narrator draws our attention to Will Mufferson as he attends to his mother:

… and last of all came the Model Boy, Will Mufferson, taking as heedful care of his mother as if she were cut glass. He always brought his mother to church, and was the pride of all the matrons. The boys all hated him, he was so good; and besides, he had been ‘thrown up to them’ so much.

Tom loathes Will and thinks him a snob. Will is deferential to the former generation. He is a constrained boy acting against a boy’s nature for the approval of the adult world. Will represents an older ideal, Tom a new, and it is not too long a bow to draw – though it is nowhere made explicit – to read in this a representation of the British and American characters in opposition. Will is a traditionalist and presumably not worth writing about, while Tom represents the new American breed.

If this seems a stretch, then reflect upon the famous whitewashing scene. It embodies American values of ingenuity and business acumen at a time when a nascent consumer culture was beginning to take hold in America. Tom is an entrepreneur. He is told to white wash the fence by Aunt Polly, but naturally, Tom has no heart for it. Instead, he convinces several boys that whitewashing is a desirable activity and makes them pay him for the privilege of doing it. Tom is a salesman here. He rebrands the activity and sells it. He makes a profit and provides a service, of a kind. Then he takes his profit and reinvests it. By using his profit to buy up the tickets handed out at Sunday School they have received for remembering Bible verses, he is able to gain credit that would otherwise be beyond him, and in so doing, he undermines a system designed to control him. Is this American exceptionalism? Is this form of trading something akin to capitalism? Tom always has a scheme to benefit himself and his friends. He is not bound by the old rules; rather, he bends them to his purpose.

The character of Huckleberry softens the cynicism of this portrait. Tom is loyal to Huckleberry, but Huckleberry is not driven by the same ambitions as Tom. When we first meet Huckleberry he is carrying a dead cat because he believes he can utilise it to cure warts. Tom would have found some more profitable use for it. Huckleberry is an outlier in this novel, even though we have come to associate Tom and Huck together. Ask anyone to tell you who Tom Sawyer’s ‘bosom pal’ is in The Adventures of Tom Sawyer, and they’re likely to answer Huckleberry Finn. Their pairing is famous. But the pedant’s answer is that Joe Harper is Tom’s bosom friend. He is twice described as such, as well as Tom’s “soul’s sworn comrade”. When they go to Jackson’s Island, Huck joins Joe and Tom. What brings Tom and Huck together is their witnessing the murder of Dr Robinson. But Huck’s life is predicated upon a different set of principles to Tom. Huck sees the treasure they find as a burden and wants to give his half to Tom. His desire to return to his life before he is ‘sivilised’ is a poignant example that there are also simpler values that risk being lost in this new world defined by wealth.

I really loved reading Tom Sawyer again. There is sheer joy in the story telling. Tom seems like the forerunner of later boy characters: Ginger Meggs; Peter Pan; Ferris Bueller. Young men who are individuals and are unbound by rules that would otherwise suppress them. But Tom Sawyer is not a perfect book. It would probably have benefitted from being written in first person, as was Huckleberry Finn, given the distinctive personal experiences of the protagonist. Also, as narrator, Mark Twain sometimes intervenes to offer an opinion, or use language that doesn’t quite fit his characters (“If he had been a great and wide philosopher, like the writer of this book …”; “So endeth this chronicle”). The novel is somewhat episodic, too, although I liked this. The story tends to wander from one incident to another until the point when Huck and Tom visit the graveyard with the dead cat. After that, their fates are increasingly entwined by a common purpose: to keep quiet about the murder they have witnessed. The narrative still meanders after this, but there seems to be a general direction it is flowing. The tension in the story caused by Huck and Tom’s pact is a convincing trope to drive the narrative. But at other times it feels like Twain has to work harder to set up his key moments. The scene in which Tom and his friends attend their own funeral is wonderful, but I had a sense as I read the story again that Twain had to go to some effort to establish all the elements in the story to make the moment plausible: going to the island; Tom’s secret return home; the increasing homesickness of Huck and Joe which forces Tom into delaying their going. Even Tom’s pretended dream told to Aunt Polly. Some of it seems contrived with long set-ups for comic effect. Nevertheless, it is all entertaining, I have to admit, and there are many comedic moments, especially involving cats, as I remember. Tom Sawyer is still more than worth a read, and better than most contemporary coming of age stories, in my opinion.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed Facebook

Facebook Instagram

Instagram YouTube

YouTube Subscribe to our Newsletter

Subscribe to our Newsletter