The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn, it is commonly written, is the great American novel. Ernest Hemingway said that, “All modern American literature comes from one book by Mark Twain called Huckleberry Finn.” T.S Eliot, in an introduction to the novel in 1950 wrote, “[it] is the only one of Mark Twain’s various books which can be called a masterpiece.” Huckleberry Finn is a sequel to Twain’s best-selling The Adventures of Tom Sawyer. It continues the story of Tom and Huck directly from that first book. At the end of Tom Sawyer, Tom and Huck find a fortune in a cave and Huck, whose father is an absentee father and a drunk, is adopted by the Widow Douglas who plans to “sivilise” him. The boys would seem to have their lives comfortably set before them, but Huck is not happy with the Widow’s “sivilising” ways and cares little for the fortune that could provide him a comfortable life. For one thing, it has separated him from his easy life as a vagrant, sleeping where he will and doing what he wants. Instead, he must attend church, learn manners and accept that his time is now organised. And another thing, the promise of the fortune brings his abusive father back, hoping to gain control of it.

As for the greatness of the novel, it has always been in dispute and it seems to remain that way. The book was immediately banned by The Concord Public Library in Massachusetts in 1885, and it has been the subject of bans for most of its history. The newspaper, St. Louis Globe-Democrat, wrote that year:

It deals with a series of adventures of a very low grade of morality; it is couched in the language of a rough dialect, and all through its pages there is a systemic use of bad grammar and an employment of rough, coarse, inelegant expressions. It is also very irreverent. . . . The whole book is of a class that is more profitable for the slums than it is for respectable people.

This initial assessment dismisses what is now perceived to be one of the novel’s strengths. Instead of adopting the paternalistic tone of Tom Sawyer – an adult writing about a young boy – Twain chose to write Huckleberry Finn from Huck’s perspective and in Huck’s voice. He foregrounded this intention in an explanatory note, that several dialects had been employed, and that he wrote from an experienced ear:

The shadings have not been done in a hap-hazard fashion, or by guess-work; but painstakingly, and with the trustworthy guidance and support of personal familiarity with these several forms of speech.

Huckleberry Finn was the first novel to be written in a vernacular for the entire novel. Twain sought to capture the flavour and character of the period when the American character of independence and innovation was burgeoning. But in doing this, he was also giving a voice to Huck, whose perspective is significantly different from Tom’s. “We look at Tom as the smiling adult does” Eliot wrote: “Huck we do not look at—we see the world through his eyes.” Eliot’s introduction helped to fashion opinion about the novel and you can read it in its entirety by clicking here.

While we may dismiss the criticisms first levelled at the novel by the St. Louis Globe-Democrat, other criticisms have to be considered more carefully. In 1957 the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) stated that the book was racist, and it has since received criticism for its treatment of race, particularly for its frequent use of the word “nigger”. My personal reason for returning to this novel was that I wished to read James Percival’s James, which is based upon Huckleberry Finn, but told from the perspective of the slave, Jim. In Huckleberry Finn, Jim and Huck form a friendship on the river as they each escape oppression. For Huck, he seeks to escape the controlling violence of his father who locks him in a cabin while he is absent. Jim seeks to escape his present circumstances, too. As a black slave he is little more than chattel, able to be bought and sold without regard for his humanity. His current owner, Miss Watson, sister to Widow Douglas, intends to sell Jim further south, which would separate him from his family. Presumably, Everett’s rewriting of the story from Jim’s perspective is intended to address racial aspects of the novel.

From my own point of view, I think Huckleberry Finn is a story that intends to be critical of slavery and has something to say against racism. Upon this matter, many people will remain divided. In his introduction to the book in 1950 T.S. Eliot wrote:

… the style of the book, which is the style of Huck, is what makes it a far more convincing indictment of slavery than the sensationalist propaganda of Uncle Tom’s Cabin.

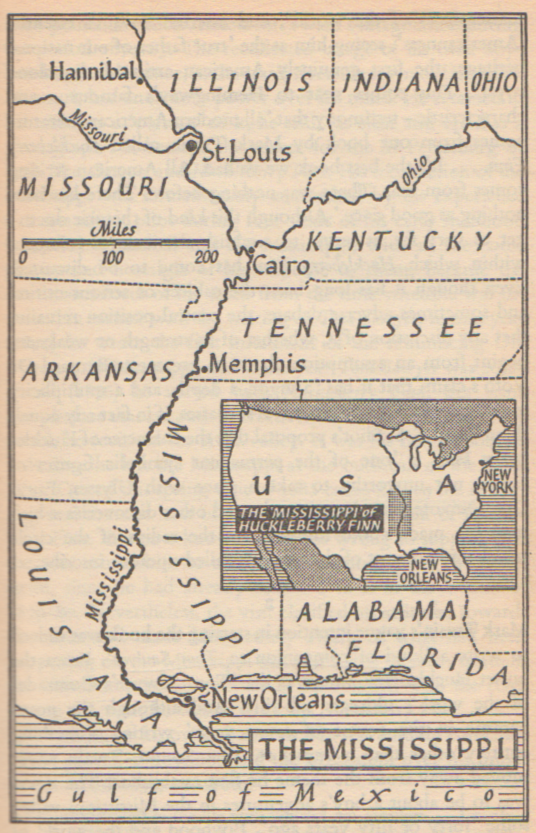

Eliot characterised Huck as a “passive and impassive” chronicler of his world. Unlike Tom, who seeks to shape reality through his imagination, Huck’s story is shaped by the flow of the Mississippi, and he usually cedes authority to those around him. We see through Huck’s eyes and we hear Huck’s voice, but Huck’s greatest moment comes when he struggles to overcome the racial prejudices and truths that have been adopted by his contemporary society. Although, I will qualify that statement to acknowledge that Twain is not always consistent from a modern perspective. Sometimes the narrative becomes more important than the issue – the shear exuberance of Tom’s imagination, for instance, which drives it forward in the novel’s latter stages – and the serious questions of race and humanity become secondary.

To put the question of race into some context, it is important to understand the novel’s setting. The novel is set, according to the original title page “Forty to fifty years ago”. It was first published in 1884, so that makes the setting around 1834 to 1844. As a point of comparison, Everett shifts the time of the story to 1861, the year of the outbreak of the American Civil War, thereby defining the story from a racial perspective, I assume. But Twain chose not to give the story this context. The question of the abolition of slavery had long been debated in America and abroad, but in 1830s America the question had not reached an incendiary point as it later did in the 1850s and 1860s. This, I think, makes Uncle Tom’s Cabin a more political text – it had practical influence over people’s thinking about the question of slavery – whereas Huckleberry Finn, emerging from the hijinks of Tom Sawyer, is a subtler and more problematic in its approach. For instance, it cannot have escaped Twain’s notice that he sets his novel in the 1830s when slavery was being abolished in Britain. The Slavery Abolition Act, which extended the jurisdiction of the Slave Trade Act 1807, was passed in the British parliament in 1833. Huckleberry Finn is set in a period in which slavery was being phased out in England, while it remained institutionally and socially embedded in America for decades more, and then it took a civil war to abolish it. This is a far subtler rebuke of the history of American slavery and racial politics.

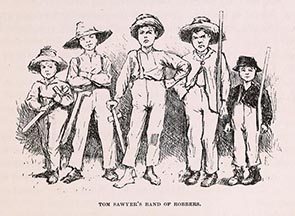

Huckleberry Finn highlights the issues of racism and slavery while Tom Sawyer skirts about the issues. In Tom Sawyer, ‘Jim’ is a young black boy who is barely mentioned, and the portrayal of Injun Joe – an evil Indian – may be problematic to modern eyes but not so within the novel, itself. But Huckleberry Finn emerged from that first novel, and sometimes that is significant when considering the novel’s achievement. While reading Huckleberry Finn, I found myself making comparisons with Tolkien’s The Lord of the Rings (LOTR). This is not a whimsical aside, but a serious consideration of the structure of the two novels. Both novels emerged from a lesser work written to appeal to children. Both novels had to deal with the world created in the original work at the beginning of their new story before they became more serious and their world larger. The long-expected party that begins LOTR recalls the unexpected party that begins The Hobbit. When Tolkien began writing LOTR he had no idea where the story was going. It meandered a little in a world that still seemed appealing to children, except that the second chapter, integrated from earlier drafts in the process of rewriting, raised the stakes of the story. The same is true of Huckleberry Finn. Twain is tied to the events of his last story, and he now has to deal with the expectations of an audience who have embraced the fun of Tom Sawyer. The trick Tom and Huck play on Jim in the second chapter – slipping off his hat while Jim is asleep and hanging it on a limb – leaves Jim convinced (at least he says so) that he has been ridden by witches and he has seen the devil himself. It is an incident reminiscent of the superstitions and fun of the first book. As is Tom’s plan to start a gang to engage in highway robbery. His insistence that his friends sign an oath in blood and do things as they’re done in books is, from Tom’s point of view, de jure. But Twain cleverly breaks the expectations of his reader. For the first time we are seeing Tom outside the narrative of his own story, from Huck’s point of view. When Tom makes a plan for his gang to attack a group of Spanish merchants, “rich A-rabs”, accompanied by “two hundred elephants” and “six hundred camels”, Huck is somewhat sceptical. He still believes in Tom, so he takes him at his word. His reservation is limited, amusingly, to his doubt that “I didn’t believe we could lick such a crowd”. But when the mighty host turns out to be little more than a Sunday school picnic, the gang is limited to stealing hymn books, a ragdoll, along with doughnuts and jam. T.S. Eliot wrote: “Huck has not imagination, in the sense in which Tom has it: he has, instead, vision. He sees the real world …” Huck questions Tom’s reality and records Tom’s response:

… if I warn’t so ignorant, but had read a book called ‘Don Quixote’, I would know without asking. He said it was all done by enchantment. He said there was hundreds of soldiers there, and elephants and treasure, and so on, but we had enemies which he called magicians, and they had turned the whole thing into an infant Sunday school, just out of spite.

This is the moment when Huckleberry Finn becomes its own book. We have seen Tom through Huck’s eyes and we understand that Tom is beholden to a world of book learning that Huck has no tolerance for:

… I judged that all that stuff was only just one of Tom Sawyer’s lies. I reckon he believed in the A-rabs and the elephants, but as for me I think different. It had all the marks of a Sunday school.

Despite its departure from Tom Sawyer the novel remains episodic: a picaresque adventure worthy of Don Quixote. It’s a feature of the novel which I actually enjoyed in Tom Sawyer, and it still works here. And Twain reprises certain plot elements of Tom Sawyer too, like old favourites, for his audience. Huck fakes his own death to escape his father, and when he returns to town he returns in a dress as an unconvincing girl. He escapes to Jackson’s Island where he meets Jim, the setting for the boys’ period of freedom from parents and responsibility from the first book. Like the first novel there is a tension between the civilised world and the world of freedom sought by Huckleberry: to not be constrained and controlled by society; but also, for Jim, hoping to gain freedom and his humanity. Jim and Huck’s escape downriver on the raft opens up the novel to greater possibilities. What was once merely play with Tom is turned into real-life struggles for Jim and Huck. An incident on a stricken steamer endangers their lives. And Jim must constantly hide during the day to avoid recapture. Sometimes, it is life and death.

However, while I find Huckleberry Finn to be an immensely entertaining book, I also feel it is an inconsistent book, despite its purported greatness. It has an ungainly structure, not just because of the transition from the Tom Sawyer narrative to the Huckleberry Finn narrative, but because it is a patchwork of different stories throughout that loosely cohere. I sometimes felt the efforts made by the author to keep the plot ‘flowing’. This is most obvious between the end of chapter 16 when the raft is damaged by a steamboat and the succeeding chapters which feature the feud between the Shepherdsons and Grangerfords, two families Huck and Jim become mixed up with when stranded on shore. Twain apparently stopped writing the novel for about three years at this point, and it feels different when chapter 17 begins. We are being told a different story. Huck has mostly become an observer of action rather than the subject of the novel. No one remembers why or how the feud began, but it is just as hotly contested as ever. Both family’s meet on the neutral ground of church each Sunday bearing arms, just in case. When the son of one family elopes with the daughter of the other, the bloodshed is inevitable.

But the feud is not enough to sustain the narrative beyond a few chapters, and besides, it is a much darker incident than we have come to expect, regardless of the murderous Injun Joe of Tom Sawyer or the two murderers we have already seen on the stricken steamship in Huckleberry Finn, arguing over whether they should kill their companion who has tried to cheat them. Immediately after the raft is struck by the steamboat, Twain relegates the role of the river, which has hitherto been a catalyst for story, to a series of meetings and incidents that are more picaresque in their nature.

The chapter after the Grangerford/Shepherdson feud is abandoned we are introduced to two new characters, fleeing from angry crowds whom they have duped. The whole centre section of the novel is dominated by these two conmen who join Huck and Jim. One claims to be the French Dauphin who would have been Louis XVII, but for the French Revolution. The other, as if to match this disingenuousness, claims to be a descendant of the Duke of Bridgewater, and rightful heir to that title. The King and the Duke’s have various schemes to scam money from townsfolk along their way. They collect money to reform pirates; they perform a truncated and much bastardised version of Shakespeare’s Romeo and Juliet (much more amusing than the fatal feud); and even claim to be the heirs to the recently deceased Peter Wilks so that they might steal his hidden fortune from his family. This is all fodder for the plot, but Twain seems to have a serious point, also. The King and the Duke are like grown-up versions of Tom Sawyer, with his schemes to dupe people in the original book: to make others pay to whitewash his fence or to gain credit by falsely qualifying for a Bible at Sunday school. In essence, Twain has returned to the original impetus for his stories as he pushes the plot forward. But in Tom Sawyer, Tom’s schemes reveal something of the American character: of independence, of intelligence and of seizing opportunity. But the King and the Duke take matters beyond that. They are charlatans; tricksters; scammers. Merely by the appellations they adopt, Twain seems to suggest a corruption of the old world and the tenuous claims for power made by royalty and the interests of old foes like England. It is a step beyond the entrepreneurial efforts made by Tom; a step implied by their comic fate.

The strange thing about reading Huckleberry Finn is that it always remains entertaining and brilliant, but there is a lingering sense that the novel goes off track a little after the incident in which the raft is struck by a steamboat. As though the more serious elements of the novel, like the issue of slavery, is never quite a fit for a book that grew from Tom Sawyer. Nevertheless, Twain gives Huck a great scene in which he struggles with the moral questions of slavery, as he understands them. As modern readers, we have to understand that for Huck, Jim is someone’s property, so helping Jim to escape is tantamount to stealing. Jim is sold by the King and locked up in a hut on the property of Silas Phelps. Huck is aware not only of the moral question of helping Jim, but the contempt he will suffer from those he knows: “It would get all around, that Huck Finn helped a nigger to get his freedom; and if I was to ever see anybody from that town again, I’d be ready to get down and lick his boots for shame.” Huck wonders if he is essentially bad, even though, as a modern audience, we would think that helping Jim gain his freedom is a good thing. Huck cannot pray because he cannot lie to God about what he feels. What sways Huck is Jim’s humanity and friendship, as he has experienced it during their time together.

And I got to thinking over our trip down the river; and I see Jim before me, all the time, in the day, and in the night-time, sometimes moonlight, sometimes storms, and we a floating along, talking, and singing, and laughing. But somehow I couldn’t seem to strike no places to harden me against him, but only the other kind.

Twain has given his character a genuine moral struggle to overcome here, and Huck chooses to support Jim based on friendship, if not a sense of equality. Huck’s self-loathing is born from a belief that he has not learned enough, has not received the correct indoctrination, a lack for which he ironically blames his act of ‘wickedness’ on ignorance: “There was the Sunday school, you could a gone to it; and if you’d done it they’d a learnt you, there, that people that acts as I’d been acting about that nigger goes to everlasting fire.” Huckleberry Finn uses the ‘N-word’, as it is now politely referred to, and it is rightly jarring; so much so that the NAACP called it out in 1957. But here we see that it is possible to question the tenets of slavery, even if the character who makes the struggle cannot fully articulate the problem. For me, this was one of the greatest moments of Huckleberry Finn; its most mature realisation as a work of art.

But that’s not how things remain. Like the LOTR, Huckleberry Finn reverts somewhat to the tone of its predecessor. In LOTR the hobbits return to the Shire to find that Sharkey, the leader of a gang of ruffians, has taken over. We learn that Sharkey is, in fact, the wizard, Saruman, who has escaped from Orthanc. But ‘Sharkey’, as a name, seems more childish, even if it is meant to mean a ‘man of skill or cunning’. There is a change of tone in the narrative as the novel draws to a close, as though returning to its more comforting roots. Even so, for the first time we see the newly-returned hobbits use the skills they have learned on their adventures to expel Sharkey. That’s the point, after all, for what point would there be in the adventure if the characters had learned nothing? But it seems a different matter in the case of Huckleberry Finn. No sooner has Huck made his momentous decision to help Jim escape, than Tom Sawyer strolls back into the story, as though we’ve really been waiting for the fun guy to return, all along. Tom is the nephew of Mrs and Mrs Phelps, who have Jim imprisoned in their hut. Huck has already introduced himself to them as Tom in order to get nearer to Jim. It helps that they know who Tom is but don’t know what he looks like. For Huck, helping Jim will be a simple matter of getting him out of the hut and putting distance between him and the Phelps property. Except that Tom has other ideas.

Eliot defended this last section of the novel, and I agree that it remains amusing, because it is satirical of romantic literature, and it is simply silly. I like that. Yet, while this last section of the novel is highly entertaining, returning us to the hijinks of Tom Sawyer, the entertainment is fuelled by Tom’s imaginative world of books to the detriment of Jim’s real-life dilemma, that he is an imprisoned slave and his life appears to be on the line. Tom hits upon one crazy idea after another, lifted from the pages of books like The Count of Monte Cristo; romantic notions about how Jim should act as a prisoner. He must keep a journal on a shirt, he must saw off the leg of the bed to release his chain, he must have a rope ladder hidden away even though the cabin is at ground level, and he must needlessly dig himself out with a knife. “You got to invent all the difficulties” Tom tells Huck. All this is done over a period of weeks when Jim could simply escape. At one point, he even leaves the cabin in which he is imprisoned to help Tom and Huck move a heavy grindstone inside so that he might carve a coat of arms upon it! Not only is this closing section of the novel an awkward return to a narrative that we left behind with the “A-rabs” and elephants early on, but Tom seems to display a blatant disregard for Jim’s safety for the purposes of his own entertainment (the denouement, notwithstanding). It is entertaining stuff, because Tom seems an innocent and it is crazy, but there is also a feeling that Tom is Twain’s surrogate here, comically adding difficulties to spin out the plot. It’s a nice satire of prison literature, but it leaves the reader feeling concerned for Jim until the ending is revealed.

Some of this may make it sound like I dislike Huckleberry Finn. I do not. I understand that it is a book of its time, and so we should expect that some of its values will not align well with our own. And it is not a perfect novel by any stretch. But it is still entertaining and I enjoy many of the elements of the story which I can also find reason to criticise. In short, there are still reasons to read this book. First, it is genuinely entertaining. Also, Twain was deeply familiar with the Mississippi River and the novel is a good representation of the life around the river at that time. So, it is an interesting historical document, too. And if that is not enough to want to read the novel, it may be that, like me, you are interested in what Percival Everett has done with the story: so it is worth reading Huckleberry Finn before moving on to James. However, the novel deserves to remain relevant on its own merits, whatever shortcomings it has been judged to have, or will be judged to have in the future.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed Facebook

Facebook Instagram

Instagram YouTube

YouTube Subscribe to our Newsletter

Subscribe to our Newsletter

No one has commented yet. Be the first!