Tusker Smalley, a former Colonel in the British military stationed in India, dies at the end of Staying On while his wife, Lucy, is at the hairdressers getting her hair blue-rinsed. It’s hardly a spoiler to say this since we are informed of this fact in the very first sentence of the novel. Tusker receives a letter from his landlord, Mrs Lila Bhoolabhoy, and he dies just after he has sacked his Indian servant, Ibrahim (again), and locked his dog in the garage, irritated with the animal. Staying On subsequently returns to the events leading up to Tusker’s death as well as the earlier years of Lucy’s and Tusker’s marriage, in which the key decisions and successive disappoints that led to their staying on in India after Independence in 1947, when everyone else they knew returned to England, are teased from the narrative.

Staying On is one of those almost perfect novels you rarely come across. It is surprisingly funny as well as tragic. It portrays the end of English power in India through the experiences of the Smalleys, but their relationship is also touching, believable and complex in its own right. It hints at the new India arising, through aspirational capitalists like Mrs Bhoolabhoy, at the absurdity of life through the sexual proclivities Frank Bhoolabhoy is forced to endure at the hands of his wife and the drunken irrational outbursts of Tusker, himself. This is a novel that reminded me as much of Tom Sharpe as Graham Greene.

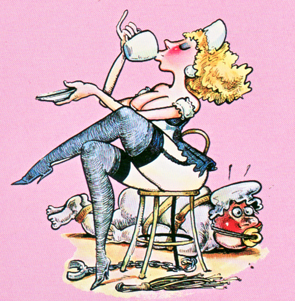

If a criticism is made of the novel it might well depend upon the reception of Paul Scott’s portrayal of Mrs Bhoolabhoy, I feel. I found it funny, especially since it reminded me of Tom Sharpe, but there are legitimate criticisms that might be made about that. Sharpe was purely a comic writer, so caricature, exaggeration and a healthy dose of wild absurdity were necessary. Scott’s novel has elements of Sharpe in the first half, particularly, but it eases into a more sombre tone as Lucy’s concerns about her own fate if her husband dies – left alone in India with little money to support her – become pronounced. Mrs Bhoolabhoy’s sexual demands upon her husband are reminiscent of the sexual behemoths that dominate their weaker men in Sharpe’s novel, often providing the catalyst for mayhem and misadventure, death and violence on an hilarious scale. When Frank Bhoolabhoy wakes stark naked in bed with his wife one morning, his mouth and nose half-smothered in her immense breasts

he is surprised because he has no memory of how he got there:

He wondered whether while he slept she had crept into his room and carried him over her shoulder to her own bed, stripped him of his pyjamas and then lowered him on top of her. Since he had daily waking evidence that he probably spent most of his sleeping hours in a state of readiness, he supposed it would have been quite possible for her thus to have availed herself of the opportunity to enjoy what otherwise went to waste without his having to wake up and consciously co-operate.

Frank’s attempted affair with Hot Chichanya while visiting Ranpur is no less a lesson in the sexual power of Indian women to emasculate:

Next evening she greeted him in full Koshak Dance uniform which apart from the whip which he eyed unhappily would have been interesting to divest her of but it seemed for the moment that she intended to remain fully clothed while Mr Bhoolabhoy ‘and these two other nice boys’ danced round her in a circle. The two other boys wore nothing but red leather boots and red y-fronted briefs.

Lila Bhoolabhoy literally has a stranglehold upon her husband, demonstrated aptly in his contorted efforts to extricate himself from her bed in the morning as she sleeps: One just slipped the head away from the grappling hold inch by inch.

She owns the Smith hotel in which the Smalley’s are accommodated and she asserts her authority over Frank whenever she feels the need. Frank is not only her husband but also her manager, and she thinks nothing of asserting her professional authority over him as nuptial dominance. It is possible to be critical of this aspect of the novel, since Lila Bhoolaboy’s relationship with her husband – indeed, her very character – skirts close to the more simplified caricature appropriate for a Sharpe novel. It’s problematic, since Lila also represents the drive of modern India, with her desire to better herself by buying into a hotel consortium. Caricature is often the handmaiden of satire, and the book sometimes promotes sympathy for the Smalleys and the old India under the British by denigrating the new India.

At the same time, Scott’s novel is structurally neat, since the Bhoolaboy’s provide some parallels to the Smalleys. Tusker Smalley is a man who stayed behind after the British rule ended primarily because he had few options. Unlike Lila Bhoolabhoy, he is not an ambitious man, and Lucy feels she has been left in the position of a box-wallah’s wife, forced to associate with the Indians since they are the only British couple left in Pankot, in a world of,

. . .emerging Indian middle class of wheelers and dealers who with their chicanery, their corrupt practices, their black money, their utter indifference to the state of the nation, their use of political power for personal gain were ruining the country or if not ruining it making it safe chiefly for themselves.

Yet the heart of the novel remains the relationship between Tusker and Lucy, disappointed and sad though it may be. Scott’s treatment is perfect. Tusker, an old-man-given-up-on-life, having allowed his circumstances to diminish to fit his means and his ambition, but curmudgeonly, nevertheless; Lucy, a woman who loves her husband but is haunted by memories of England, her thwarted ambitions for a stage career and her teenage memories of a man she barely knew, Toole. Tusker’s curmudgeonly nature is comically realised in a scene in which he reads a history of Pankot by Mr Maybrick. Every time Tusker finds an inaccuracy he cries Ha!

, which grates on Lucy’s nerves, until he finally asks her to confirm the last person buried in St John’s cemetery. Mr Maybrick, Lucy confirms, to which he replies, There you are! He’s got that wrong too. He says here it was old Mabel Layton.

Lucy, on the other hand, demands our sympathy. If Frank Bhoolabhoy’s life is consumed by his wife’s ambitions, Lucy’s has been diminished by Tusker’s lack of ambition:

. . . the reason I have no friends, because all our friends are your friends, Tusker, not mine, and – yes, I will say it - they are all black and I want you to realize that it has been much on my mind recently that if you had not recovered from your attack I would have been left alone here, alone.

Notwithstanding the racist overtones, Lucy’s plea speaks of her isolation and disempowerment. Her husband was diminished when his career ended after Indian Independence, followed by his own ineptitude. She has seen her social circle not only evaporate, but she has suffered a complete reversal in her social status as a result. For a woman of secret passions and longing ambition, it is sad that the best that can be said of their marriage is that she had been a good woman

, meaning a wife.

It is possible, given modern social concerns, that some might question aspects of the novel’s portrayal of women, particularly Indian women, as well as racist attitudes in its characters. But Staying On should be read with an open mind and an understanding that it represents a period in history and people whose declining social status makes their attitudes and concerns realistic. Many Indian’s were ruthlessly exploited under the British Raj, and the reversal of fortune suffered by Lucy and Tusker would be difficult for them. The caricature of Lila Bhoolaboy aside, these are real people who deserve our sympathy and understanding on a personal level. Paul Scott’s treatment of his subject is skilled, well-structured and entertaining.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed Facebook

Facebook Instagram

Instagram YouTube

YouTube Subscribe to our Newsletter

Subscribe to our Newsletter

No one has commented yet. Be the first!