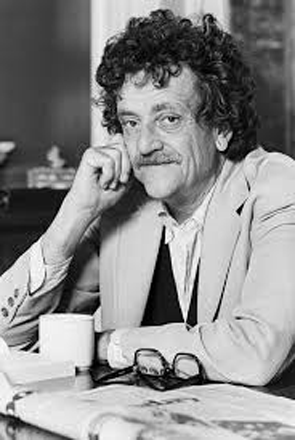

Anyone who has read Kurt Vonnegut would be familiar with his eccentric style. In his most famous novel, Slaughterhouse 5, Vonnegut makes the bombing of Dresden the central event of the book which he claims was more destructive than the bomb dropped on Hiroshima. Vonnegut survived the bombing by hiding in the slaughterhouse of the title. Yet the book is not a straight historical fiction or autobiographical account. Billy Pilgrim, Vonnegut’s surrogate in the novel, is also captured by aliens and transported to the planet Tralfamadore.

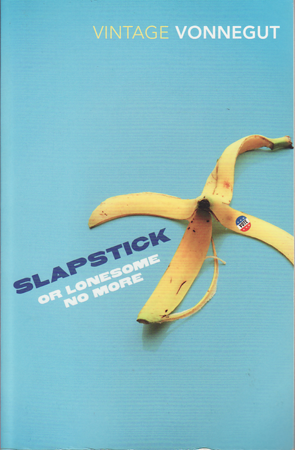

Slapstick or Lonesome No More exhibits more of that same eccentricity, although it is not as accomplished and lacks the passionate drive of Slaughterhouse 5. Slapstick is predominantly written from the point of view of Dr Wilbur Daffodil-II Swain, a former paediatrician and President of the United States, a position which is now irrelevant, since the country has collapsed into a collection of warring states headed by local despots and kings. Swain’s final act as president is to sign over the land covered by the Louisiana purchase of 1803 from Napoleon Bonaparte to the King of Michigan for a dollar. In the end he never receives the dollar. Other than that Wilbur Daffodil-II Swain is tired and defeated, living out his final days in the Empire State Building, with the island of Manhattan almost deserted because of the ‘The Green Death’ which has swept the city. Faced with the additional problems of variable gravity – some days people can barely walk, other days gravity is so light all men have erections – and swarms of Chinese now shrunk to microscopic size but far in advance of American ingenuity, the increasingly irrelevant president has nothing left to do except write his memoir. If Slaughterhouse 5 was marked by its vehement anti-war sentiments, Slapstick or Lonesome No More is marked by a disaffection with the promise of America and a meditation on the meaning of family.

Vonnegut explains in the opening sentence of his prologue, This is the closest I will ever come to writing an autobiography.

Vonnegut tends to fictionalise his own life or insert himself somewhere into the narrative of his books. In Slapstick… the connection is with the death of his sister, Alice, who died of cancer in 1958. Her husband died in an accident two days before she passed away in hospital, leaving Vonnegut to help raise their children. As the novel begins, Vonnegut and his brother, Bernard, are in a plane travelling to the funeral of their father’s brother, Alex. Between them is an empty seat which reminds Vonnegut of his long dead sister.

Alice is fictionally represented by Eliza, Wilbur’s sister, in the main part of the novel. Both Eliza and Wilbur are born physically grotesque and their parents, horrified, exile them to Vermont where they live in a mansion full of books, with servants to attend their needs. And because all they have ever seen of the world is stupidity (…all the information we received about the planet we were on indicated that idiots were lovely things to be.

), they assume that is what is expected of them, so they affect the outward show of imbecility, while secretly teaching themselves all manner of things, including multiple languages. Together, Eliza and Wilbur are geniuses. Breaking their psychic connection by physically isolating them renders them only average, or as they characterise themselves, as Betty and Bobby Brown

: as normal and boring. It’s a nod to the importance of ties to other human beings, a theme central to the novel. Later, when they reveal their intelligence, they will be separated, with Eliza being institutionalised while Wilbur begins his strange career that leads him to the presidency.

Superficially, Vonnegut’s prologue may seem to have little to do with the fantasy of the aging president and a dying America, but Vonnegut’s personal story is a thematic preamble to the story the mind I was given daydreamed

as he and Bernard fly to their destination. Vonnegut says that he and his brother, who is an atmospheric scientist, were given very different sorts of minds at birth,

yet they share a love of the same kind of jokes: Mark Twain stuff, Laurel and Hardy stuff.

Like Eliza and Wilbur, their minds are different, but they have a connection. But while they might share an emotional temperament,

. . . because of the sorts of minds we were given at birth, and in spite of their disorderliness, Bernard and I belong to artificial extended families which allow us to claim relatives all over the world.

He is a brother to scientists everywhere. I am a brother to writers everywhere.

This is amusing and comforting to us both. It is nice.

It is lucky, too, for human beings need all the relatives they can get – as possible donors or receivers not necessarily of love, but of common decency.

Vonnegut’s advocacy of “common decency” over “love” is central to the novel:

I have had some experiences with love, or think I have, anyway, although the ones I have liked best could easily be described as ‘common decency’. I treated somebody well for a little while, or maybe even for a tremendously long time, and that person treated me well in turn. Love need not have had anything to do with it.

When Wilbur tries to tell his sister that he loves her, she rejects the sentiment because she doesn’t like it:

‘It’s as though you were pointing a gun at my head,’ she said. ‘It’s just a way of getting somebody to say something they probably don’t mean. What else can I say, or anybody say, but, I love you too

?’

The belief that common decency

is more crucial to human happiness is central to the novel, since it is Dr Wilbur Daffodil-II Swain’s idea to give all the people of America new relatives in an attempt to wipe out loneliness. Decency does not rely upon consanguineal ties. By allocating social security numbers, each person is randomly allocated a new middle name with a numerical suffix from one to twenty. Someone with the same middle name is instantly a cousin. Anyone bearing the same middle name and number is a sibling. The plan is the cornerstone of Swain’s bid for the presidency: I said that all the damaging excesses of Americans in the past were motivated by loneliness rather than a fondness for sin.

Swain relates how an old man later comes to him,

. . . and told me how he used to buy life insurance and mutual funds and household appliances and automobiles and so on, not because he liked them or needed them, but the salesman seemed to promise to be his relative and so on.

He further explains:

. . . he had been drunk for a while, trying to make relatives out of people in bars. ‘The bartender would be kind of a father, you know -’ he said. ‘And then all of a sudden it was closing time.’

The old man’s story recalls uncle Alex from Vonnegut’s prologue who went looking for new brothers and sisters and nephews and nieces and uncles and aunts, and so on, which he found in A.A.

despite him having no drinking problem. It reveals the hollow connections consumerism offers.

The theme of family pervades the prologue. There is not just Vonnegut's reminiscence about his dead sister and uncle. He also reflects upon the way the family was changed by the First World War when members felt compelled to abandon their German heritage. Vonnegut says they became a lot less interesting. Indianapolis, a place which had symbolised family - a place to which members returned to belong to that thing called family, devolves into just another someplace where automobiles lived, with a symphony orchestra and all.

when Vonnegut’s relatives leave after the First World War. I think Vonnegut's point is that family is defined through acts of decency between people rather than ideological positions, or by intellectual or creative connections, like Bernard and Vonnegut’s professional ties, for instance.

Of course, Swain’s artificial creation of families seems ridiculous with subtle overtones of Communist ideology. There are characters in the novel who refuse to be a part of it, but on reflection it seems no more ridiculous than the artificial ties of commerce and consumption which are characteristics of the second incarnation of the American Dream and national identity. If Indianapolis has lost its character, it has followed the general trend of the American Dream, if I read Vonnegut right, which has devolved from the promises of the Declaration of Independence to the consumerism that was a mark of the country’s rise after World War II.

There are other little satirical asides as well which reflect Vonnegut’s antipathy towards religion, like the Church of Jesus Christ the Kidnapped, whose followers heads are apt to jerk widely about, always expecting to see Jesus returned to them in the next instant, or the invention of the Hooligan

, a device that allows you to speak to people in the after world, which reveals only that they are all terribly bored with an eternity to spare.

While Slapstick is not always his most accomplished work, Vonnegut’s novel is still at its best as a clever satire of American exceptionalism and the problems of family and loneliness in a modern consumerist society.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed Facebook

Facebook Instagram

Instagram YouTube

YouTube Subscribe to our Newsletter

Subscribe to our Newsletter

No one has commented yet. Be the first!