Red Side Story was published this year, fourteen years after Shades of Grey. Jasper Fforde has had other projects on the go during that time. He published two more Thursday Next novels after Shades of Grey, he wrote his Dragonslayer books for children, as well as his stand-alone novels, The Constant Rabbit and Early Riser. He also had a two year hiatus, a matter which he briefly addresses in his afterword in Early Riser, but says he can’t explain why it happened. Altogether, there was suddenly fourteen years between trips to Chromatacia. Mind you, ‘Chromatacia’, the name of Fforde’s world in which people are organised hierarchically in their social and professional lives based upon the level of colour they can perceive, never appears in Shades of Grey. Fforde used the name in postings he made to his website as the book was being released back in 2010, but in the story the where of the novel was just as enigmatic as the when. Fforde’s concept seemed so different that the experience of reading the novel could also be turned into a minor puzzle if the reader so chose. The when can be pieced together from clues peppered throughout, just as the reader can make a good guess at what the Something that Happened – the event that changed the world and brought about Chromatic society – was. But the where of this world was only described in the context of the characters’ understanding: based on neighbouring towns and nomenclature that mean nothing to us, except as a fictional construct.

It’s on this point that I find the most striking difference between Red Side Story and Shades of Grey. Shades of Grey is an enigmatic story whereas Red Side Story is more perspicuous. This is evident in Fforde’s use of his chapter epigraphs. In Shades of Grey each of the chapter epigraphs is a citation from the rules of Munsell, the purported founder of Chromatic society. The occupants of Chromatacia adhere strictly to these rules (except where they are nonsensical or problematic, and there is always a workaround – loopholery – to fix that!) In Shades of Grey the epigraphs are sometimes relevant, sometimes not, but all serve to characterise the Collective in which the characters live, as well as some of its bizarre rules and practices. However, while in Red Side Story the epigraph to the first chapter quotes Munsell, continuing the practice from the first book, the purpose seems different. The vaguely expository character of the epigraphs from Shades of Grey have become direct exposition in this book. Fforde, from the start it appears, wishes to dismantle many of the mysteries left by the first book. “The name of the Collective shall be Chromatacia” Munsell’s founding document states: “It shall be divided into four sectors …” Another break from the practice of the first book is in the epigraphs to chapters after the first. Almost all epigraphs in the novel are quotations from someone called Ted Grey, from a book or document titled “Twenty Years Among the Chromatacians”. The title of Ted Grey’s book implies an outside to the world Fforde has created: an implicit observer of the Chromatacians. And almost all epigraphs to chapters fill in the blanks or seek to remind us of salient information that explicitly addresses the content of the chapter in some way.

This, and the direction of the story, make Red Side Story feel less original than its predecessor. Because Fforde’s explication puts us on more familiar ground and there have been enough clues in Shades of Grey to expect the direction taken by this novel. After writing Shades of Grey, Fforde tells us on his website, he originally toyed with the idea of producing a prequel to the story. Fortunately, this didn’t happen. Prequels that fill out the details hinted at in any narrative can feel superfluous. But his instinct to do this suggests the need he felt to explain his world. Fortunately, this story begins shortly after Eddie, Jane, Tommo and Violet have returned from the expedition to High Saffron, rather than venturing into Chromatacia’s past. Courtland Gamboge is dead and Eddie and Violet are under suspicion. There will be an enquiry which will almost certainly find them guilty of his murder – their guilt is already presumed – and they will be sent them to the Green Room, where Chromatacians are sentenced to death or may elect to go to die by being exposed to a certain deadly shade of green. But first, before the trial is to happen, they undertake one more mission to Crimsonolia, a nearby town supposedly destroyed by the Mildew, a disease, to look for spoons, a source of wealth and identity in Chromatacia, which Munsell’s rules ban the production of. And what happens in Crimsonolia will change not only their fate, but everything they think they know about their world.

In the interests of not spoiling the story, the best way to characterise this progression is to acknowledge that Fforde is now on familiar ground when it comes to plotting: that we are familiar with this story. In The Matrix, Neo discovers the true nature of his world and the course of his life changes. The television series Lost, George Lucas’ THX-1138 and The Maze Runner books and film franchise work on the same principle: of the protagonist discovering the true nature of their world, with the direction of discovery working from the inside to the out: an escape or emancipation.

And the novel is also more allusive than the first. It’s there in the title, Red Side Story (and no, the title of the first novel, Shades of Grey, is not an allusion to E.L. James’ novel of soft-porn escapadery, published a year after Fforde’s). The opening of the novel has shades of Hamlet with the arrival of a troupe of Orange actors who perform plays imbued with appropriate Chromatic ideology approved by the Collective. They perform a lot of minor dramas before their main piece, a play adapted from the musical, Red Side Story (yes, an obvious allusion to Leonard Bernstein’s and Stephen Sondheim’s musical, West Side Story, based on a book by Arthur Laurents who had a recognizable debt to Shakespeare), The Tragedy of the Chromatically Non-compliant and Clearly Idiotic Romeo and Juliet. As propaganda, the title, alone, is hilariously heavy handed, and its tone is extended in the opening’s parody of Shakespeare’s original play.

- Two households, opposite in colour,

- In fair Violetta, where we lay our scene,

- From ancient and very wise taboo breaks to new stupidity,

- Where uncivil hues make civil hues unclean.

This is the kind of colouring-in (if you will excuse the pun) that Fforde is good at: embellishing and enriching his worlds. The intertextual allusions are many. There is a neat, if somewhat obvious, parody of the Star Wars scene – “These are not the droids you are looking for” – and the allusions to The Wizard of Oz remain abundant: Emerald City; Dorothy; flying monkeys. Eddie and Jane even find a Tin Man. As for the players who wander into the narrative, much like the players from Hamlet, they serve a functional role in the narrative, at least. They may perform plays that are little more than sanctioned propaganda (you could take in a performance of Greys and Dolls, for example), but in the Greyzone at night they also secretly perform subversive originals of the plays for the working underclass. Instead of the chromatically themed bastardisation of Romeo and Juliet, they perform the original with an honesty and poignancy that Eddie finds moving. And like the living books of Ray Bradbury’s Fahrenheit 451, they spend their lives committing the original plays to memory in the hope of a future society more amenable to them. Like the book penned by Ted Grey, which provides the epigraphs to most of the chapters, their devotion is not just a hint at what has happened in the past of Chromatacia, but helps to draw back that curtain to hint at a world beyond Munsell’s ideology. It’s a neat reminder that we, also, are products of social and ideological constructs which, for the most part, seem invisible in our day to day experience.

It is hard to say more about this book without spoiling its surprises and the reading pleasure it offers. I think it is a step below the first book, but that always seems to be the case when an author or producer begins to expand and explain their world. Mysteries are more alluring than specifics. But with that said, Red Side Story remains an intriguing read and impressive for its inventiveness. Sure, Fforde has expanded his universe and he has taken us places we might have guessed at, but the encompassing mysteries remain intact for a third book in the series. Even so, the most bizarre elements of the story that seemed inexplicable in the first book – as I mention in my first review – now make sense. And the significance of the Apocryphal Man and the Fallen Man are now evident, too, as are the Heralds and even the strange trick Jane does with her eyes in the first book: being able to control her irises so that her ability to see in the dark is not revealed. In short, Fforde’s story delivers on its promises and is a worthy addition to his oeuvre.

Jasper Fforde

Jasper Fforde is the prolific author of the Thursday Next Series, The Nursery Crime Series, and The Dragonslayer Series for young adults. His novels are witty and deeply inspired by the culture of reading. Red Side Story, the sequel to Shades fo Grey has now been published, fourteen years after Shades of Grey was first released

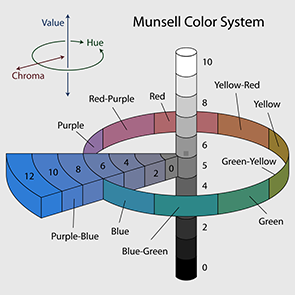

Albert H. Munsell

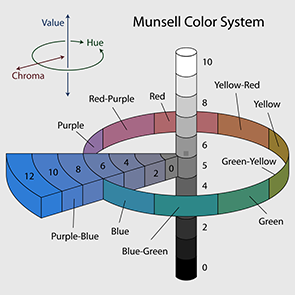

Albert Munsell was an American painter who first developed a system to categorise colours according to three properties of color: hue (basic color), value (lightness), and chroma (color intensity). The image below shows a cross section of Munsell's model. It demonstrates how colour changes according to these properties. Munsell's system was an early attempt to describe colour numerically. In Shades of Grey Jasper Fforde has alluded to Munsell's pioneering work by naming his prophet, Munsell, after him. Munsell's rules delve into every aspect of society and are restrictive. Like Munsell's original colour model, the Rules are an attempt to codify every aspect of life and therefore create a society of Stasis. Characters like Jane Grey and Eddie Russet are inspired by their curiosity and intelligence to question these Rules and begin to form a plan to subvert them.

The Munsell Colour System

The ability of Munsell's system and systems that superceded it to desccribe colour mathematically is integral to the display of colour on computer screens and television in the modern world. For example, the colour swatch below can be described in various notations. I've chosen three common notations to show how colour can be denoted mathematically:

#2e8735: this is the hexadecimal system used on this website. Each number is a score between one and sixteen, with letters representing numbers greater than 9. The first two numbers represent Red, the middle two represent Green and the last two represent a value of Blue.

125-66-83: These numbers represent the same green swatch above based on the HSV (Hue, Saturation, Value). This is based off the colour wheel where there are values 0–360, one for each degree. Each primary colour is on the wheel at positions 0º (Red) 120º (Green) and 240º (Blue).

82-24-100-9: this value represents the green swatch above based on its CMYK value, a colour model based on the CMY colour model, used in colour printing, and is also used to describe the printing process itself. The abbreviation CMY refers to the three ink plates used: cyan, magenta, yellow, and the K refers to the key, black.

In Shades of Grey this colour is known as Lincoln, a colour swatch valuable for its ability to relieve pain

RSS Feed

RSS Feed Facebook

Facebook Instagram

Instagram YouTube

YouTube Subscribe to our Newsletter

Subscribe to our Newsletter