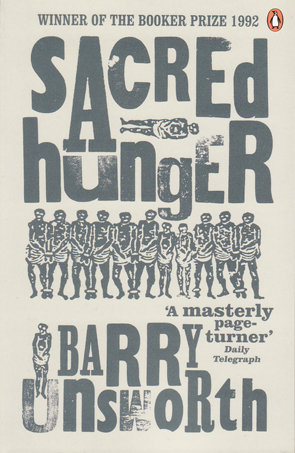

There is a scene in Barry Unsworth’s Sacred Hunger which anticipates last year’s Man Booker shortlisted novel, Washington Black. In Washington Black Erasmus Wilde gathers his slaves together to watch his overseer slice the head from the body of a young slave, William, who has hanged himself. The scene is gruesome and Wilde stages it to make a point: He was my slave, and he has killed himself. He has therefore stolen from me.

Wilde explains the purpose of this piece of theatre: I understand that some of you believe you will be reborn in your homelands when you die.

There can be no blunter demonstration of the status of negroes in a nineteenth century sugar plantation; they are mere chattels to be disposed of as the master decides, and any act of self-determination will be frustrated to the very end, even beyond the grave.

In Sacred Hunger Captain Saul Thurso, in charge of the slave ship Liverpool Merchant, tells Matthew Paris, his ship surgeon, a story about a voyage where the negroes refused to eat and could not be persuaded to do so by flogging. I discovered from my linguister,

he tells Paris, that they believed that by dying they would get back to their own country.

His solution is as theatrical and inhuman as Erasmus Wilde’s: I’ll tell you what I did, sir. I had the slaves brought up on the deck and in full view of all I cut off the heads of those who had died with a cleaver from the galley.

Despite similarities between the scenes the comparison also demonstrates differences in the two novels. First, is perspective: Washington Black is the narrator in Edugyan’s novel and the story is related from his horrified point of view. The scene is essentially a plot point, since the beheading forms a part of Washington’s motivation to escape the plantation. In Sacred Hunger we do not ‘see’ the beheading directly but through Thurso’s telling of it to Paris, and this makes all the difference. Thurso and Paris are engaged in a debate about the treatment of slaves which is philosophically underpinned by assumptions about humanity. Paris has already tried to persuade a dying slave to eat but has had a bowl of rice thrown in his face. Despite this, Paris believes in a common humanity he shares with the slaves. They need better conditions and he thinks he can persuade them to cooperate and thereby save their lives. But Thurso is convinced that what is needed is punishment and fear: It is in the mind … You have got to bring ’em to the right frame of mind. And when you have animals to deal with, it is done by fear, sir, not persuasion.

Sacred Hunger is essentially a philosophical novel which transcends its historical milieu, and I think this is what ultimately makes it a great novel as opposed to a good novel which Washington Black assuredly is, as well as telling a well-rounded story with complex characters who are not delineated in the narrative by race. Clearly, one might object to this statement, because characters are defined by race – white people are not sold in the novel. But Sacred Hunger, while drawing inspiration from an evil trade that exploits race, is essentially concerned with human nature which transcends race, and is instead defined through systems of power and trade.

Trade is at the very heart of this book and forms a fairly neat dichotomy with nascent ideas of evolutionary theory, yet to be consolidated by Darwin. Advocates of trade include Erasmus Kemp, son of William Kemp, who commissions the building of the Liverpool Merchant along with Thurso’s voyage, and Thurso himself who was never handed anything on a silver plate.

Unsworth’s narrative condemns the practice of slavery, but it is the exigencies of trade which ultimately debase humanity in this novel. Slavery is only one aspect of that. The point is overtly made by the sardonic Major Redwood, commander of a garrison in Florida, who explains the exploitative potential of trade to Erasmus Kemp, who has just witnessed the signing of a land treaty between Indians and George Watson, Superintendent of Indian Affairs:

They are prevailed upon to cede their lands by treaty. Trade is the thing that has undone them, this great blessing of trade. Watson tells them they should be grateful for the advantages of trade. Campbell tells them they should give up land to their English brothers for the sake of the trade goods they will get by it. They have hunted over these lands for centuries without ever knowing that what they needed for happiness were muskets and looking-glasses and beads and bits of printed cotton. Now they are persuaded that they cannot live without these things. Strange, is it not?

But is it not only American Indians or African negroes who are transformed by trade. Other minor characters like the English factor, Timothy Owen, languishes in an English colony hoping to make his fortune, and a fort governor who has invested everything he has to get his post has no other option than to stay in a debilitating climate and recoup his money. Meanwhile, Erasmus, whose father has suffered a terrible loss from trade that Erasmus has worked hard to restore, sees trade as a social good that benefits individuals by supplying needs and raising the standard of living. It’s a fact made equally clear to Paris by Kireku, a negro who chastises Paris for his idealism:

I build hut need man guard dat hut, built boat need boatman, do trade need porter for cargo. Need dem all de time, not jus’ when dey wan’. Dat de way ting go dis worl’, Paree, where you been? Dis de real worl’, you no sabee dat?

Yet Kireku is not only defending the benefits of trade. As a negro who was once enslaved, himself, he now seeks to effectively enslave another negro for his own benefit. This is what he is justifying to Paris. He needs access to his labour all the time, not just when they want. Kireku is morally debased by the promise of trade, just as some black races are debased by trading slaves with white slavers like Thurso in Africa, by capturing neighbouring blacks in tribal wars and selling them. The Kru people who are coal black

sell slaves who are lighter in colour

than themselves to Thurso, a hint that race alone is not the determining factor, but the dictates of trade: of supply and demand. Other characters in the novel – I mean white characters, now – are essentially enslaved by the commercial system, too. Paris writes in his journal, …the fact is, they [the sailors] cannot choose. All these men are driven by the direst poverty. I do not think there is one among them who would not quit the sea tomorrow if they could…

Paris tells Thurso, There are many would think the keeper is behind bars too, sir, for all his pistol and whip.

Delblanc, an artist who befriends Paris at the fort, explains to Paris how the East India Company exploits workers by paying them in company currency and inflating the prices for goods in a closed economy: …they are all a company of whiter negroes here and it is the same in the other trading forts.

Set against the ideology of trade are Utopian ideals espoused by Delblanc and Paris. Delblanc perceives that money has been elevated in society to a ‘sacred’ status. The introduction of this religious term suggests a nod to Max Weber’s belief in the Protestant Work Ethic, a belief based upon Calvanism that hard work, discipline and frugality demonstrate laudable Christian ideals. This ethic is certainly evident in Erasmus’s efforts to erase his father’s debts and make his fortune. But Delblanc unpacks the ideology of ‘’sacred hunger’ like a moral declension. If money is sacred, he reasons, So then must be the hunger for it and the means we use to obtain it.

To indebt a man transforms his humanity:

. . . he becomes a flesh and blood form of money, a walking investment. You can do what you like with him, you can work him to death or you can sell him. This cannot be called cruel or greed because we are seeking only to recover our investment and that is a sacred duty.

Delblanc appears to suggest a philosophy close to Thurso’s – Let the most oppressed people under heaven once change their thinking and they are free

– but he is, in fact, advocating the opposite; not changing one’s thinking to acquiesce and accept a dominant ideology, but to eschew the dictates of power created by trade. Delblanc’s is an ideology informed by Enlightenment thinking: … the state of society was artificial and the power of one man over another merely derived from convention

; government must always depend on the consent of the governed.

Delblanc’s thinking, married with Paris’s still-forming beliefs around emerging evolutionary theory, produce an ideological alternative to mainstream Western values of the time. Paris has already been imprisoned for publishing his views about evolution and questioning church theology. When Paris explains the views of Pierre Louis Maupertius about how errors in reproduction can, over time, change a species, Delblanc sees the obvious: But that would mean that we ourselves are the result of error also, that we need not have been as we are.

How can there be an absolute moral position, when all is chance?

Sacred Hunger tells the story of the voyage to trade slaves and by doing so, rescue William Kemp’s fortune. Naturally, much goes wrong giving Paris and Delblanc an opportunity to experiment with their Utopian beliefs in equality and living as in nature, perhaps a nod to Rousseau’s idealisation of the ‘noble savage’. What elevates this book, I think, is the complex self-awareness Unsworth affords his characters. Having explored the iniquities of trade, Unsworth also allows characters to speak for its importance and to question the idealistic notions that Paris harbours. Most importantly, Paris has an insight that his Utopian dream is also culturally specific; that in the end he cannot impose it upon the negroes he expects he can elevate through his beliefs:

Men living free and equal in a state of nature … What gave us the confidence to suppose that a state of nature could only mean what it meant to us, a notion of Eden, a nostalgia of educated, privileged men?

Despite his scientific bent, Paris is also a prisoner of his cultural conditioning, since his Utopian instinct is an atavistic desire for the prelapsarian state.

There is so much that could be written about this novel from so many different perspectives and so many characters, as well incidents and ideas for which there is no reasonable space in this review. What I’ve done here is to try to give a brief sense of the flavour and thinking behind this book. It is these insights, the complexity of the characters and their relationships, and the rich detail of the story – its breadth of humanity, its moral complexity and ironies – that make Sacred Hunger a truly great novel.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed Facebook

Facebook Instagram

Instagram YouTube

YouTube Subscribe to our Newsletter

Subscribe to our Newsletter

No one has commented yet. Be the first!