Mary Beard’s SPQR takes its name from a catchphrase the Romans had for their city, Senatus Populus Que Romanus, or ‘The Senate and People of Rome’. It’s a rather apt title for the book, although its scope is wider than the Republican period the title suggests. Beard ends her history with Caracalla in 212 CE, when he extended citizenship to all occupants of the Roman world. So, her book also takes in the Imperial period of Rome, mostly covering the first fourteen emperors (minus a few short reigns). This gives her history a rather wide range because her chronology also reaches back into the legendary past of Rome, to its founding, purportedly by Romulus and Remus, with other references even as far back as Troy, from which another version of the founding myth has it, Aeneas returned to establish a second Troy on the Italian peninsula.

Her treatment of the founding myths underscores part of the point Beard is trying to make about Roman history: that for much of Roman history, very little is known. She points out, Plutarch, the second-century CE biographer, philosopher, essayist and priest of the famous Greek oracle at Delphi – extends to as many modern pages as all the surviving work of the fifth century BCE put together, from the tragedies of Aeschylus to the history of Thucydides.

And what is written about these early years of the republic may often be taken for the retrospective re-imaginings of ancient writers. What Beard means is that nations form narratives about their origins, and narratives have a way of providing neat rationales. The story of Brutus, one of Julius Caesar’s assassins, is possibly one such example. Brutus claimed to be the descendant of one of Rome’s first consuls, Lucius Junius Brutus, who was instrumental in expelling the second Tarquin king, Tarquinius Superbus, and thereby helping to establish the republic. The connection helped to the conspirators represent the murder of Caesar as an act loyalty to the Republic; of protecting Republican institutions against a tyrant. Ironically, their actions led to civil war and the downfall of the Republic, instead.

Julius Caesar’s later reputation also benefitted from this kind of historical retrofitting. Livy, an ancient historian, told one version of the Romulus story that had him hacked to death by senators. This, conflated with other versions of the story – that Romulus had been snatched from the Earth during a storm (a kind of apotheosis) – has obvious echoes with the death of Caesar and his later deification.

Was Brutus’s ancestor really responsible for expelling the second Tarquin king, Tarquinius Superbus, and thereby helping to establish the republic? It is hard to know for sure, Beard would admit, but the purported role of Brutus’s ancestor certainly provided a legitimate gloss to Brutus and his co-conspirators against Caesar, to the point that one wonders at the temptation of contemporary sympathisers to provide him with this ancestry. This questioning of evidence is a large part of Beard’s book, which is more unusual for a work obviously aimed at the general public.

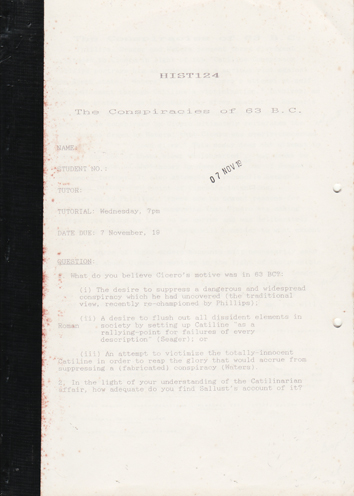

It is this problem of evidence that justifies what initially seems a strange structure to this book. Instead of beginning with Rome’s early years and giving a chronological account, as much as is possible, for the rise of the Republic, Beard begins her history in 63 BCE, during the consulship of Cicero when Rome was faced with the Catiline Conspiracy. The conspiracy of Catiline was a supposed plan to overthrow the senate and take power in Rome with the aid of forces outside the city. I say “supposed” because the consulship of Cicero – this, his finest moment – raises the problem, once again, of ancient evidence. Beard points out that the first century BCE saw an explosion of written material available to the ancient historian. Cicero, alone, was a prolific writer of speeches, commentaries and poetry. But Beard acknowledges that there exists a traditional, unproblematic account of the Conspiracy, based on writers like Sallust and Cicero, himself, as well as niggling questions the evidence raises, especially since what we know is based on writers antipathetic to Catiline. So Beard gives her reader the traditional account, which may be familiar, and then attempts to construct a possible alternative version, in which Catiline is forced out of the city due to political rivalry, perhaps even due to Cicero’s ambition as a New Man in the consulate (Cicero knew the consulship was his chance to make a reputation, especially since being a “New Man” meant no-one in his family had ever held the position) which forces Catiline into a position of opposition. It’s an interesting theory which has been gaining currency since well before I attended university and was made to write an essay for a first-year history course on the subject. Beard’s approach to the book had me digging through an old filing cabinet, and I found the essay. I’ve posted it here, partly for my own nostalgia, partly as a demonstration of Beard’s point: that when looking at the history of this politically fractious period, there is very little that one might deem as clear cut.

Beard’s beginning with the conspiracy also speaks to why this book is an interesting read. Certainly, it’s a technique designed to draw a reader in – begin with something juicy – but it is also predicated on the belief that history must be meaningful. By beginning with Cicero, Beard has access to a familiar Roman to whom she can return the reader, who characterises much of the period that forms the bulk of this book, but who also wrote about the period, too. Cicero’s lack of political ancestry provides a segue into the problems of legitimising one’s place in the political landscape, his career as a lawyer provides insight into the problems of government in the provinces (Cicero’s speech against the corrupt government official, Verres, made him my hero in school, my suspicions about his motives during my writing of the essay on the Catiline Conspiracy, less so), and his life covers everything from the problems of owning slaves, of finding a third husband for his daughter, Tullia, of hosting Caesar and his retinue of hundreds for dinner, to the problems of taxes and owning properties. All this, as well the fact that his life runs concurrent with the rise of Caesar and into the beginning of the Civil Wars after Caesar’s death, that eventually saw Augustus come to power as Rome’s first emperor. Naturally, Cicero is of less use to Beard as she moves into the Imperial era of Rome, but she uses other writers for her purpose, if not quite so successfully. Pliny the Younger, another prolific writer of Rome, and like Cicero, a governor of a province, provides an interesting insight into the life of an governor, as well as the relationship of the emperor to the decision-making processes in local governments. Her brief examination of Polybius, a Greek intellectual detained by Rome, is a topic that has always fascinated me. Like much of Beard’s book, Polybius tried to account for Rome’s success, and his discussion of Rome’s mixed constitution in Book 6 of his work is perhaps one of the best accounts of political science from the ancient world.

Apart from personalising history through key characters in this way, Beard makes the people of the period seem a little like us. One of the problems Beard returns to again and again, from the opening paragraphs that discuss early Rome’s annexation of its nearest neighbours, right through to the end of the book in which Roman citizenship is granted to all in Roman provinces, is what did Romaness look like? The expanding empire took in all manner of cultures with many languages. Beard traces the ever-changing makeup of the senate as it became more representative of its far-flung regions, as well as emperors appointed from those regions and the ordinary people of the empire, who were affected to varying degrees by their Roman overlords.

Beard devotes a chapter to these ordinary people – after all, it was many of them who would receive Caracalla’s gift of citizenship in 212 CE – concerning how they lived and how much being a part of the Roman world actually affected their traditions and their lives. One of the most stunning things I read concerned the lot of women in the Roman world. Often used as alliances between families through marriage, especially among the political elite, they were married at remarkably young ages. To use the example of Cicero again, when he re-married he took a wife forty-five years his junior. She was in her mid-teens. Beard explains there was plenty of evidence in the epitaphs of ordinary people for girls being married in their mid teens and occasionally as young as ten or eleven.

I found this particularly creepy in the case of Aurelius Hermia, a butcher, whose epitaph describes meeting his wife when she was seven, small enough that he took her on his knee.

Beard’s reckoning of birth rates also provides insight into the lot of Roman women, who actually enjoyed more liberty than other ancient women, like the Greeks. Beard calculates that:

Simply to maintain the existing population, each woman on average would have needed to bear five or six children. In practice, that rises to something closer to nine when other factors, such as sterility and widowhood, are taken into account. It was hardly a recipe for widespread women’s liberation.

A modern reader may find other topical concerns in Beard’s account of Rome. For instance, the last part of Beard’s history deals with the pressures of Rome’s evolution due to its expanding empire. If Caesar’s conspirators looked back to the ousting of the Tarquin king as a means of justifying political assassination, it is no less likely that a modern reader will find something to relate to in the cultural pressures that Roman expansion created, alongside our own modern world that is being changed by technology and globalisation. Beard doesn’t make this point explicitly, but our modern concerns seem echoed in Beard’s history as I read it: of the struggles of the Jews at Masada for independence, of Boudicca’s bloody rebellion in England, and the whispering kind of descent one finds in Tacitus’s biography of his father-in-law: they create desolation and call it peace.

For these reasons I found Beard’s account of Rome engaging. Not so long ago I tried to read a history of the Borgias – a fascinating subject by anyone’s standards – but its plodding ‘this, then this, then this’ account of the period had me put the book aside. Beard shapes the history for her reader, ties things together, makes sense of the whole thing, as well as informing the reader about the limits and problems of what can be known or presumed. This was done entertainingly, and I thought that was impressive for a generalist history of such a broad historical scope.

For anyone interested, the book also includes a vast list of further readings at the back, an adequate index and some basic maps for all the relevant periods at the front of the book.

The book would be a great introduction for anyone unfamiliar with Rome and provides an interesting perspective and interpretation for those more familiar with the subject. For me, being most familiar with the Republican period, I also found the book valuable because it gave the fall of the Republic a broader historical context.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed Facebook

Facebook Instagram

Instagram YouTube

YouTube Subscribe to our Newsletter

Subscribe to our Newsletter

No one has commented yet. Be the first!