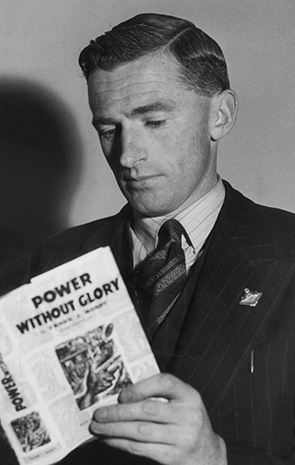

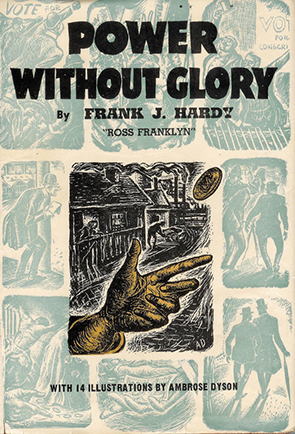

Power without Glory is not a book everyone will enjoy, and as the years pass it might become one of those books that has historical interest but isn’t likely to be read widely as entertainment. The book was self-published in 1950. Frank Hardy, its author, knew his book was political dynamite. He had difficulty even getting the book typeset and printed, and a company that had contracted to fold the printed sheets, ready for binding, pulled out when its workers began to read what they were working with. The book was based on extensive research into the labour movement from the early 1890s until the late 1940s, on the Communist party, of which Hardy was a member, upon the machinations of government during the period, both state and federal, as well as scandals over the Mungana Mining Leases, which is fictionalised in the novel in minute detail. John West, the fictional version of the then well-known sport promoter, John Wren, a man who had gained power through his vast wealth over the selection and election of political candidates, and had been implicated in fraud and even murder, was the focus of Hardy’s intent to reveal corruption and the betrayal of the working classes in Australia. Because of this, the physical production of Hardy’s book was not the only matter of concern. In the years during which he was researching and writing his book, he always had to remain careful not to draw attention to his project, given the political and financial power that might be brought against him. The prospect that the manuscript might be taken from him, or that the pages being produced from the print run might be seized – which had cost Hardy significant sums – was very real.

As it turned out, when the book eventually began to sell well in 1950, Hardy was arrested for criminal libel. His case was to be the last criminal libel case tried in Melbourne (all cases since have been civil). Strangely enough, the many political and business revelations in the book were ignored in the indictement. Instead, Hardy was tried for impugning the reputation of Ellen Wren, John Wren’s wife. The argument was that she was readily identifiable in the book as Nellie West, since Ellen Wren was John Wren’s wife, and John West is unmistakably John Wren. The issue was that Hardy’s story has Nellie West having an affair with a bricklayer, and later a child, Xavier, to him. The prosecution’s tactic helped to acquit Hardy, since it became suspicious that he was forced to defend a libel charge for suggesting adultery, but on the matter of murder and fraud, Wren had made no application for remedy.

The novel was also published in a period of political upheaval for Australia. The Chifley Labor government was defeated in 1949 by Robert Menzies’s Liberal-Country Coalition. Labor had courted workers through the trade union movement since Federation in 1901, but had increasingly received competition from the Communist Party (CPA), whose ideologies overlapped some key Labor tenets. Hardy’s book intersected with political moves to oust the CPA from Australian politics. Chifley had stood against the CPA in 1949 when it attempted to use its influence to draw some of Labor’s support, using the miners’ strike as a political fulcrum. In response, Labor used strike breakers to undermine the CPA’s tactic. In 1951, Prime Minister Menzies, concerned at the rising power of Communist nations, attempted to legislate the CPA out of existence, but was struck down by the High Court (Australia’s equivalent to the American Supreme Court), and was subsequently defeated at referendum in an attempt to change the constitution to allow him to do this. This was the political climate in which the book was published.

Given this, I will first talk about why this book may be inaccessible for many readers now, followed by what the book has to offer.

Two of the biggest problems for readers now is the subject matter, itself, and the way Hardy uses that material. Much of the book is so dedicated to the discussion of politics, factions, business dealings, the culture of racing and other gambling sports, corruption and crime, all through the prism of John West, John Wren’s fictional counterpart, that the detail can become overwhelming. This was obviously not such an issue in the 1950s. Hardy’s contemporary readers were readily familiar with the political issues of the time, as well as the many politicians and personalities who are represented throughout the book. John Wren, himself, was still alive (he died 1953). The implications of Hardy’s story were explosive. They implicated Wren in a network of crime and the influence of politicians for his own gain. His portrayal as a working class man who betrays his working class origins by courting the working class in his early career to grow his wealth through his betting tote, but effectively exploiting them: who supports conscription during World War I, primarily out of interest to protect his own wealth; his in-principle support of fascist ideology against Communist ideals, which Hardy is naturally sympathetic to; and his associations with the Catholic Church – his use of bribes and donations to control the church – in order to effect his political intentions, are all told with great detail that is cumulatively damning. But the detail is sometimes relentless. New characters are introduced into the story throughout the novel, even in its final pages, often associated with a new scheme or scandal. The narrative swerves from one political issue to another, often with little preamble. It takes some patience and faith to focus on those details and wait to see how Hardy weaves them into a mostly coherent narrative. And given that the details are mainly of historical interest now, that is something of a burden for modern readers who are not necessarily students of history.

“Power becomes more mighty and satisfying when exercised by remote control. He did not want glory, he wanted power – power without glory.”

Power with Glory, page 380

Power without Glory was Frank Hardy’s first novel, and in some ways that shows. He is more committed to his research and politics than the conventions of the novel or the needs of readers. But it would be disingenuous to say that Power without Glory isn’t a moving story. The novel captures the temperament of the period, but it is also a very personal story that is quite affecting. I think the irony is that while Hardy sought to demonise Wren/West, he also makes him a somewhat sympathetic character. The most ready comparison I can think of is Orson Wells’s Citizen Kane. First, there is the fact that Wells, like Hardy, based his character upon a real man, William Randolph Hearst, a newspaper mogul of the day who wielded enormous power. Wells’ portrayal of Hearst drew harsh criticism, not to mention that Hearst had great social influence during that period. Citizen Kane failed to win the 1941 Oscar for best picture and Wells was even booed. Notwithstanding that, viewing Citizen Kane, now, distant from its contemporary controversies, Kane is a somewhat sympathetic character. His lonesome death, the mystery of his life, and his increasing alienation, despite his wealth, make him someone we want to know. That, after all, is the whole point of the film.

West has a comparable trajectory. We first meet him at the age of twenty-four. Like many, he has been the victim of the 1890s economic depression. Like thousands of others, he is sacked. But he is determined not to be poor, and the first part of the book is about West’s endeavours to create some wealth by running an illegal totaliser, a betting venture that draws the working poor from around his district. West deflects criticisms that he is exploiting his own class by saying that he is fairer than the other totes and always honest with his customers; that he provides something that is wanted. His attempts to keep his tote running, despite the constant raids by police, and to keep himself out of jail, result in ever-increasing illegal measures, as well as his own growing understanding of how to manipulate the legal system, and eventually the political realm when that impinges upon his interests, too. But Hardy introduces an interesting tension in his portrayal of West. As a political ideologue he cannot help but be openly critical of West; of the corrupt means by which he gains power, of his cynical use of politicians and religious leaders to get what he wants, and the abominable way he treats his family, never able to separate his sense of the power he wields in the world from his personal life at home. In short, West is something of a monster, and his corruption stands as a representation of the corruption endemic during that period.

Yet, Hardy writes beyond the tenets of his own political ideology as he tells John West’s story, and thereby creates a more complex character with whom we can be engaged. West uses his money and power to strike out at his family in his attempts to control them. When his daughter, Marjorie, decides to marry a German, West cuts her off. When his other daughter, Mary, is exposed to the plight of the poor, she becomes sympathetic to Communist ideology and works to improve their conditions with her new husband. West, who would rather that England align with Germany against the Russians than accept Communist support in the war, disowns his youngest daughter in a misguided attempt to get her to change her mind. Hardy foregrounds the issue of West’s power as a thematic concern throughout. It is hard to admire West because he is unable to understand any human transaction except through the application of power and force: “John West was but the total of things he had had to know and do in furtherance of his ambitions.” But the inevitable decline of West’s power and the mess he makes of his personal life make him a strangely affecting character. He is a man who at once understands the destructiveness of his own actions, but has no other means by which to engage the world or understand it. His slow alienation from the basis of his own power as well as his family might be the inevitable result of his actions, but West’s belated insight into the emptiness of his life is a poignant conclusion to a novel steeped in the minutiae of business and politics.

“Where had his wealth and power led him? He could have all the things that money could buy, but the will to possess them, the ability to use them, had deserted him …”

Power without Glory, page 659

As a result, it is the personal stories that lift the narrative above the level of an historical curiosity. Of West’s brother, Arthur, for instance, hopelessly loyal to his prison companion, Bradley. Or West’s son, John, who cannot cope with the demands made by his father. Or of West’s wife, Nellie, whose affair with a bricklayer is an expression of her loneliness and sadness, and the sad outcome of the affair, a child whom West barely tolerates in his home and will not speak to. The narrative comes alive in these moments, and helps to shape the overarching story of West’s career. We also are forced to consider the nature of power through these moments, too. Hardy provides many authorial asides throughout his book that read like the meditations of a Sun Tzu – how power is established, maintained, the threats to power and what makes it desirable. But in the end, the story of West’s desire for power is reflected in the title of the book through various iterations. The title ironically paraphrases the end of the Lord’s Prayer, which is rather apt, since West seeks to control the church through his donations, but personally rejects the church until later in life, when he begins to sense the waning of his power and his own imminent death. Then there is the subject of his own anonymity. Having pulled the strings of power from the shadows all his life, he finds a newspaper article that mentions him, and that reveals almost nothing is known of him, personally. His belated attempts at philanthropy are little more than a desire to create a positive public persona. Finally, there is no glory in the way West achieves his ends, and his inability to separate the means by which he works with the means by which he seeks to control his family. West’s power has waxed and waned, as it inevitably must, but what he leaves behind is a sad wreck of a family. That will be his enduring legacy.

Power without Glory will continue to be an important book about the growth of Australia in its political infancy, as well as a curious insight into the machinations and controversies of the period. But as time takes us further from that period, the interest in that aspect of the novel will inevitably wane for the general reader, especially since the book is written with an assumed understanding of the period and people it references. Nevertheless, while the novel isn’t as artful as Wells’s movie, it is still an enduring character study of power; of how it corrupts, but how it may also betray those who believe they might wield it.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed Facebook

Facebook Instagram

Instagram YouTube

YouTube Subscribe to our Newsletter

Subscribe to our Newsletter

No one has commented yet. Be the first!