Two Reviews of this book by Skelequin and Skep

Piranesi

Susanna Clarke

- Category:Fantasy Fiction

- Date Read:25 June 2025

- Year Published:2020

- Pages:245

- Prize:Women's Prize for Fiction 2021

Skelequin

I adore Piranesi so much that this was my second reading of it, and I think I might have enjoyed it even more this time. What a novel! Granted, I definitely agree with the previous review by Skep: this is a story you will want to experience entirely blind if you can! Here’s Susanna Clarke’s description of her own work, deliberately brief and open-ended: it is “about a man who lives in a House in which an Ocean is imprisoned.” If that sounds appealing, take it as a sign to read the book without any further information. Susanna Clarke is such a talented writer, even her one-sentence elevator pitch is poetry. She’s amazing.

This is a fantasy novel, but, in my opinion, it is a mystery even more than that, the mystery being the world itself. We follow our protagonist Piranesi as he uncovers the secrets of the strange, infinite House that he inhabits. I had the privilege of reading Piranesi for the first time two summers ago. It was such a joy to uncover the mystery of the House alongside Piranesi (and, since I read it in a book club, alongside my friends). The slow yet engaging drip of information, the mounting conclusion that I had never at first imagined, the reappearance of clues and details I had nearly forgotten, it’s all such an expertly crafted mystery. I love it so much.

The structure of the novel is really ingenious. It’s told through our protagonist Piranesi’s detailed journal entries, which often reference one another and even include a detailed index that Piranesi eventually uses to help refresh himself on old information and put the mystery of the world together. Reading Piranesi’s journal, which isn’t only a vehicle for the story but central to the story itself, creates such an immersive experience. Often, Piranesi’s entries will be formatted such that his observations and discoveries are explained, and, just after, his thoughts and conclusions are described. For example, an entry will be titled “The Prophet” and the next entry will be titled “I consider the words of the Prophet.” The structure allows the reader time to form their own conclusions about Piranesi’s discoveries before learning the protagonist’s interpretation, which I found so fun. It’s such a clever way to string the reader along the mystery. I consistently figured things out a couple of pages before Piranesi did, which could be frustrating in another novel, but I never felt like I was just waiting for Piranesi to figure things out so we could move on. It was fascinating to witness his thought process. He’s such a unique and charming character. I never felt frustrated with him. Although he sometimes made decisions or came to conclusions I knew better than to agree with, Piranesi never came off as foolish. In fact, he is extremely smart, just inevitably working with a very different set of experiences and biases than any reader, given his home in a fantasy world.

Piranesi, himself, is absolutely one of my favourite elements of the novel. His appreciation and wonder for the House are infectious, and I found his decidedly positive attitude admirable and never artificial-feeling. He felt very much like a real, believable human being. Since reading this book for the first time, Piranesi’s attitude has really stuck with me. He’s almost become a role model for me during times of crisis – no matter what terrible secrets he uncovers about his beloved House, he is so careful to ground himself and maintain his gentle outlook. He is unshakeably kind to himself and the world around him. I know that might not make him sound like the most interesting character, but his unique interactions with the world and with other characters are fascinating. He does have his moments of weakness that make him human. He gets angry. He feels hopeless at times. During high-tension parts of the book and moments of particularly shocking discovery, we see Piranesi struggle but ultimately succeed in maintaining his rituals of caring for his own well-being. Even at his very lowest, he holds himself to showing reverence for his environment.

One moment that particularly stuck with me comes just after what is perhaps the most monumental reveal in the novel. It’s something the reader will probably have guessed long ago but Piranesi has only just understood. I won’t spoil what Piranesi understands in this moment, but I can’t overstate that it is extremely distressing to him. There are a few pages of anger and horror at what he’s realized, but then, there is this moment: “I made my seaweed-and-mussel broth and drank it. It was important to keep up my strength. Then I took up my Journal again” (191). I know this might seem kind of silly, but I think about this moment a lot. I like to read Piranesi as a sort of allegory for chronic illness –mental or physical – which the author Susanna Clarke has spoken on. She was diagnosed with chronic fatigue syndrome before starting work on this novel. Piranesi also really speaks to my personal history with chronic psychological illness. [Minor spoiler incoming] Piranesi struggles with memory loss and, of course, lives in a world almost completely isolated from other human beings. But the novel offers so many real, effective coping mechanisms. His meticulous journal-keeping helps him find objectivity when his memory fails him and lets him express himself safely, even in isolation. His reverence for the House helps him find meaning and joy in all that’s around him. An encounter with an albatross, a particularly interesting statue in one of the rooms, the way the moon is framed in a particular window, Piranesi finds so much meaning in it all. And, of course, there are moments such as the one I mentioned where his world seems to crumble around him, but he is so careful to be kind to himself by eating and sleeping and even decorating his body by threading beads and shells in his hair. He repeats his mantra: “The Beauty of the House is immeasurable; its Kindness infinite.” I adore Piranesi – the book and the character – so much. I can’t think of any other character that has helped me so materially in times of crisis. Yes, eating and sleeping in order to care for oneself ought to be obvious, but seeing a fantasy character remind himself to do these things has reached me in a way self-help books just don’t. And with any sort of chronic illness, these things become more difficult. Piranesi – the character and the book itself – understands this difficulty and advocates that it is important, nonetheless, to be kind to oneself.

On a completely different note, something I noticed on this second reading of Piranesi is the many references to The Chronicles of Narnia! I either skimmed over or forgot the epithet at the beginning: “I am the great scholar, the magician, the adept, who is doing the experiment. Of course I need subjects to do it on” from C. S. Lewis’s The Magician’s Nephew. The Magician’s Nephew is the first novel I have a memory of reading, as a little child with my father reading it aloud to me, so this, of course, is very personally meaningful. More importantly, it’s SUCH clever foreshadowing for the book’s events. It’s the perfect, perfect beginning to the novel. There’s also a reference to The Lion, The Witch, and The Wardrobe: Piranesi’s favourite statue in the house (which is saying something, as there are hundreds of statues and Piranesi knows them all) is a faun, and Piranesi describes a dream in which the faun “was standing in a snowy forest and speaking to a female child” (16). There’s a few more things I could mention but it would be getting into serious spoiler territory. The Magician’s Nephew was always my favourite of the Narnia books, certainly partly, just because it was the first I read, and I’ve read it the most times, but also because the world that the children visit has always been wonderful and fascinating to me. Consider this description from The Magician’s Nephew: “They went on out of that courtyard into another doorway, and up a great flight of steps and through vast rooms that opened out of another until you were dizzy with the mere size of the place.” Piranesi so effectively captures the atmosphere of this world, which is only explored for two chapters in the Narnia series, and stretches it into its own novel. It is very effectively a sort of spiritual successor to The Magician’s Nephew.

All of this said, it’s easy for me to believe that this book was made just for me to love and be comforted by. It speaks so well to chronic illness and has a wonderful mystery and charming characters and so clearly pays homage to my favourite childhood story. But I really think Piranesi will be loved by most readers. It’s an expertly crafted story in an incredibly unique world. I recommend it very much.

- Date Read:10 May 2024

Skep

DO NOT READ THIS REVIEW!

I’m serious. If you haven’t read Piranesi and are even the slightest bit interested in doing so, click away from this page. Don’t look at whatever pictures bikerbuddy has added to the sidebar on the right (are we really doing this? - bikerbuddy). Don’t read anything anywhere about this book. Don’t even read the blurb on the back of the book that’s supposed to sell you on it.

I tell you this because I am in the unenviable position of having to write about a book that is, in essence, entirely indescribable. This isn’t to say that the book is dense and impenetrable; far from it, actually. Nor am I claiming that the plot is nonsensical or hard to follow; I feel that it’s refreshingly straightforward, even a little predictable at times. No, my issue here is that I don’t believe anybody can say anything about this book that can properly prepare you for what Susanne Clarke delivers.

Perhaps this is due to the surreal world that Clarke presents through the journal entries of the protagonist within it. That is all I can bring myself to say. A unique setting, and a main character with an outlook uniquely shaped by it. Anything else I could possibly add would give you the wrong impression, which I feel would lead to a less satisfactory experience. So go in as a blank slate.

Seriously though, last chance to get out of here before I actually start talking about things.

Right, so I’m still going to keep things vague going forward because I know some dummy out there doesn’t know how to listen to reason.

There is a tendency in modern media, I think, to prioritize an “efficient” story. You’ve likely heard of Chekhov’s Gun, a trope which posits that an element introduced in the narrative, if not immediately relevant, must become so at a later time. Many climactic showdowns these days are resolved by the reappearance of a minor detail or off-the-cuff remark – oftentimes a gag! – that turns out to be far more crucial than anybody could have suspected at the time (and is far more subtle than a firearm). I won’t claim that Piranesi eschews this entirely, but it does delight in introducing concepts that, plot-wise, don’t amount to anything.

You could argue that these elements (such as the appearance of the albatross and the detailed descriptions of many of the House’s statues) instead serve simply to define and explore the protagonist’s relationship to the world he inhabits. And I would agree with that. But I think many modern stories would, endeavouring to tie everything up in a neat little package, feel the need to repurpose these concepts at key moments (the albatross saves the day! The statues reveal the House’s secrets!). Piranesi wisely chooses not to do this, and allows the story to be what it is.

Of course, I didn’t know this would be the case going in; and as I read through the middle sections of the book, my general opinion towards it was kind of in two places at once. Now, I never at any point felt like I had to drag my feet to continue reading; in actuality, I devoured this one in a very short amount of time. However, we learn early on (and suspect even sooner) that the world inhabited by the protagonist is somehow distinct from what we consider the “real world”. My concern here – especially as we are fed information about the people and events that relate to the “House”, as it’s referred to – was that we would be given too much detail. That every little happening would be explained and accounted for, and, in so doing, strip this place of its magic.

As you may suspect by now, my fears proved unfounded. Clarke is careful to toe the line here, giving us just enough to playfully hint at answers, but not enough to burden us with understanding. I would agree that there are many mysteries which are most satisfying when every element is accounted for. However, this is not one of them.

So I think what we are ultimately given is a work that was carefully crafted to appear as though it hasn’t been carefully crafted. Character motivations are not fully explored; the secrets of the House are not fully revealed; closure is not fully given. This may not seem satisfying, but in a way, it is. Piranesi is set in a realm that borders on fantastical; and yet it thrives on the human and the mundane in a way that results in a somehow whimsical, yet incredibly delightful read.

If you haven’t read it yet, my advice (although if you didn’t listen to my advice a few paragraphs ago, I don’t know why you would now) is don’t overthink it, and just enjoy where it takes you.

Giovanni Battista Piranesi

Giovanni Battista Piranesi was an eighteenth century artist and engraver. He is famous for recording many of the ruins of Rome that existed at the time, about a third of which have since disappeared. Piranesi is credited with preserving a record of many of these ruins, as well as creating our modern impression of what Rome might have looked like. His works were popular during his lifetime as a forerunner of the modern souvenir for those in Europe on their Grand Tour.

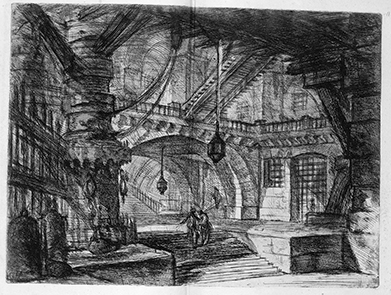

As well as this, Piranesi produced a series of sixteen prints of fantastical prisons which were vast and sprawling labyrinths. His influence on twentieth century surrealist artists as well as the illogical works of M.C. Escher, is apparent.

Susanna Clarke has taken the name Piranesi for her titular protagonist: a man who lives in a sprawling house of fantastical wonders, inspired by the fantastical prints of his eighteenth century namesake.

Giovanni Battista Piranesi, ‘Veduta del Tempio detto della Concordia’, in Le Vedute di Roma, etching, 1774

Piranesi’s etchings of Rome captured the state of the old city in the eighteenth century, and portrayed it as part of the lives of its modern day inhabitants.

Giovanni Battista Piranesi, ‘Carcere XIV’, in Carceri d’Invenzione, etching, 1760

‘Carcere XIV’ was one of sixteen etchings created by Piranesi that depicted fantastical prisons. The scenes are vast, surreal labyrinths. The images are part of the inspiration for Susanna Clarke’s setting.

Gormenghast

For those interested in the imaginative space created by a novel like Piranesi, (especially if you’ve already read it) you may wish to discover a much older series of novels by Mervyn Peake, seemingly inspired by Piranesi’s work. Gormenghast is another enormous house (or castle), so large that generations of the same family who live in it have lost touch with each other. The first two of the three volumes, Titus Groan and Gormenghast, are fantastic, magical experiences. I personally found the third volume, Titus Alone, so jarringly different from the first two, and so lacking their magic, that I wished it had never been written. Malcolm McCay, who created the BBC television series based on the books and starring Jonathan Rhys Meyers, may have felt the same way about the third book. He only dramatized the first two. The television series and the first two books, in my opinion, are well worth looking into if you like Piranesi.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed Facebook

Facebook Instagram

Instagram YouTube

YouTube Subscribe to our Newsletter

Subscribe to our Newsletter

No one has commented yet. Be the first!