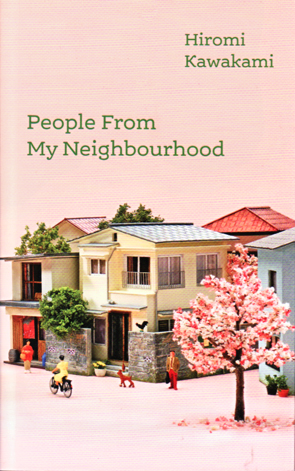

I think there is a Japanese aesthetic that is identifiable from the cover of Hiromi Kawakami’s People from My Neighbourhood. The neighbourhood is represented on the cover by a model, placing it beyond the real world, and instead suggesting a world of order, perfection and tranquillity. If this is a stereotype, it’s one that is supported by other aspects of Japanese culture: manicured gardens that are readily identifiable as Japanese, as well as the popularity of Marie Kondo, who has made her fame by teaching others how to order their lives and find happiness. The Japanese are somewhat defined by a cleaning culture, which has its roots in Shintoism.

Kawakami’s book purports to be a glimpse into a Japanese neighbourhood, but rather than the ordered and perfect world the book’s cover anticipates, we are drawn into a world of bizarre characters and events. Some of the stories arouse our curiosity, others are unexplainable forays into magic realism. Some focus on a small incident, but the temporal perspective can change suddenly to reveal the fate of characters many years later, or return us to a detail from another story that has been left tantalisingly unexplained.

Each of the thirty-six stories is only a few hundred words, possibly a thousand words for the longest, making them a variety of flash- or micro-fiction. Many don’t read as complete in themselves, since they are vignettes, building one upon another. As we read we become familiar with several characters from the neighbourhood. A few examples are: the dog school principal who patrols a dog park in a T-shirt emblazoned with the words ‘DOG SCHOOL’; Hachirō, whose family is so poor they conduct a lottery every three months to see who in the neighbourhood will raise him next; Dolly, otherwise known as Midori, whose family have returned from America, and appears to speak a magic spell when she says ‘oops!’, and later is believed to control the perceptions of those around her; or Kanae, the narrator’s best friend, who becomes a juvenile delinquent – bikers fight to the death for her – but later becomes the pride of the town when she succeeds as a fashion designer; or her unnamed sister, who finds a creature like a white dove which grows into a boy whom she marries; he later saves the planet from a meteor strike.

Some scenes have an eerie quality, some bizarre. At other times, we may be sent off balance by odd details. Kiyoshi Akai, for instance, has a dog, Blackie, that bites people. Shimizu’s older brother hatches a plot to kill Blackie, and the fate of Blackie would seem to be of most interest to us, except that the story ends with the detail that Kiyoshi Akai later becomes a crooner of old-fashioned songs in later life. The narrator finds a small child under a tree who comes to live with her. There is an unresolved tension suggested by small details that alert us to something strange about the child: “I could feel the child’s eyes on my back as I walked away. The hair on its back was thick and downy.” And then there is the humorous, like the outbreak of ‘pigeonitis’, an infection that causes people’s eyes to bulge like a bird’s, and to strut about looking for insects, unable to speak. The accumulating detail of peculiar incidents and people from one story to another builds a pitcure of a puzzling small community that tantalises us, rather than an overarching story or set of themes.

However, some stories do suggest a thematic or satirical purpose. The story of the rivalry between Yoko One and Yoko Two, two women essentially the same in every way, suggests the self-destructive flipside of revenge. ‘Sports Day’ is a wonderful dig at the bastardisation of sport through sponsorship: the games run by Marunaka Bank have prizes for “best loan evaluation, best anti-fraud strategy, best marketing of financial products, best cheque clearance procedure, and best cartoon character for their bank ads.” The narrator quips, “no event involved any form of physical activity.”

If anything, however, this collection requires that we merely open our eyes to possibility, as well as to the strangeness of the ordinary. There is a sense of the interconnectedness of the lives of people in the neighbourhood, and given the repetition of details, or the development of certain characters traits between stories, the book invites a re-reading, as does is brevity. When you flip back to the first page, you suddenly see a small detail that was of no consequence as you first began to read. When the narrator upsets the small child by removing the cloth covering it, she responds with an apology: “Oops. Sorry!”, anticipating the magical spell caste by Dolly, later on. A second reading shows us how our narrator is already seeding the details of stories to come.

Apart from being a fascinating read, this is a great book to have handy for those times when you don’t have time or the inclination for a longer work. Also, the book is physically small, so it’s good to carry around and dip into. I put it in my jacket pocket when we went out last week, and it was great to have it with me to fill in some downtime while we waited for a show to begin. Highly recommended.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed Facebook

Facebook Instagram

Instagram YouTube

YouTube Subscribe to our Newsletter

Subscribe to our Newsletter

No one has commented yet. Be the first!