I don’t know what kind of exposure others have to myth, but I know mine has been fairly piecemeal over the years. Whether it’s been through Hollywood movies, snippets of stories here and there, or reading myths from one culture or another, the result tends to be a familiarity with a lot of names and incidents from myth, but not necessarily a coherent understanding as to how the stories relate or even a coherent timeline. Nevertheless, with any sort of familiarity it is easy to see certain patterns emerge from myth: repetitions of themes or even stories. In Mythos Stephen Fry retells the Greek myths and tries to make sense of the chronology, and the meaning and cultural impact the myths have had on our own civilisation. He does this with all the wit, charm and good humour that anyone familiar with Fry’s public persona would be familiar.

And that’s a good place to start a discussion about this book. With so many books on myth published over time the obvious question for any publisher – indeed, even the public – is, why this one? Fry acknowledges his own debt to previous modern writers (Edith Hamilton, Thomas Bulfinch, Nathaniel Hawthorne, Robert Graves to mention a few) apart from ancient sources like Hesiod, Ovid and Aeschylus (again, only a few). But I think Fry has something to offer a modern audience: a conversational tone and an intention to be entertaining and engaging. When reading Fry, it is not hard to imagine that he is talking to you, especially when one is familiar with his mellifluous (a word Fry seems fond of) speaking voice. For example, here is Thomas Bulfinch on a familiar story:

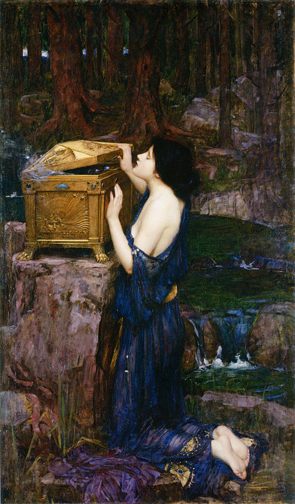

Thus equipped, she was conveyed to earth, and presented to Epithemeus, who gladly accepted her, though cautioned by his brother to beware of Jupiter [Zeus] and his gifts Epithemeus had in his house a jar, in which were kept certain noxious articles, for which, in fitting man for his new abode, he had had no occasion. Pandora was seized with an eager curiosity to know what this jar contained; and one day she slipped off the cover and looked in. Forthwith there escaped a multitude of plagues for hapless man, - such as gout, rheumatism, and colic for his body, and envy spite, and revenge for his mind, - and scattered themselves far and wide.

Thomas Bulfinch, Bulfinch’s Mythology, Chapter 2: Prometheus and Pandora

Fry creates a more engaging scene:

Epithemeus was sleeping beside happily beside her. The moonbeams danced in the garden. Unable to stand it any longer Pandora leapt from her matrimonial bed and was out in the garden, unrolling the base of the sundial and scrabbling at the earth, before she had time to tell herself that this was the wrong thing to do.

She pulled the jar from its hiding place and twisted at the lid. Its waxen seal gave way and she pulled it free. There was a fast fluttering, a furious flapping of wings and a wild wheeling and whirling in her ears.

Oh! Glorious flying creatures!

But no … they were not glorious at all. Pandora cried out in pain and fright as she felt something leathery brush her neck, followed by a shark and terrible prick of pain as some strong or bite pierced her skin. More and more flying shapes buzzed from the mouth of the jar – a great cloud of them chattering, screaming and howling in her ears. Through the swirling fog of these dreadful creatures she saw the face of her husband as he came outside to see what was happening. It was white with horror and fright. With a great cry Pandora summoned up the courage and strength to close the lid and seal the jar.

Mythos, page 136

In retelling the Greek myths Fry understands that their purpose, among others things, must have been to entertain. Pandora is not merely curious as Bulfinch allows – this is her archetypal quality after all – but she is a fully fleshed person in Fry’s hands. She is not only driven by curiosity but the dancing moonbeams suggest an ebullient personality. Yet she is also wracked by conscience, fully committed to her role as a wife, not just an instrument of Zeus’s revenge. Fry’s retelling engages the senses – we hear, we see and feel everything Pandora experiences – raising the retelling from a worthy and respectful attempt to educate and inform to a retelling that does what it must do if it is to engage a 21st century audience: entertain.

Fry’s book is also valuable to the general reader because it helps place each myth in a broader context. The story of Pandora, for example, is known by most: she releases various evils and afflictions into the world through her curiosity, leaving only hope remaining in her box (Fry insists it is a kind of jar). Also known to most is the story of Prometheus, chained to a rock on the Caucasus Mountains, his regenerating liver torn each day from his body by vultures as a punishment for giving humans divine fire, stolen from the gods. And some might even know that Epithemeus was Prometheus’s titan brother and that Pandora was sent to him by the gods as an intended punishment for Prometheus’s presumption. The gods intended she would open that box/jar. But not everyone would connect these stories, I suspect.

The theme of punishment becomes familiar as one reads Fry: that there exists a certain level of antipathy towards mankind; that the Gods fear being bettered by humans and dread the prospect that one day humans will no longer need them. Over and over the stories reveal these insecurities. For instance, there is the story of Asclepius, the father of medicine struck down by Zeus’s thunderbolt, or Sisyphus, condemned to roll a boulder up a slope for eternity in the underworld. In a sense, both their crimes were similar. Asclepius threatened Hades realm by denying him souls. Sisyphus did the same, but only after an hilarious encounter with Thanatos, the embodiment of death, whom he tricks into handcuffing himself and locks him away. Sisyphus proved himself too clever for the gods’ liking. There are also the stories of Marsyas and Arachne. Both presumed themselves to be more skilled than the Gods. Marsyas has his skin removed while alive for presuming to be a better musician than Apollo. Arachnae is driven to suicide and transformed into a spider (hence arachnid

means spider) for presuming to be a better weaver than Athena.

Reading Fry’s Mythos also gives a sense of the broader development of the myths. Fry starts with creation, taking the reader through the first gods, the emergence of Second Order

gods under Gaia and Ouranos (Uranus), the eventual emergence of the Olympians led by Zeus and the war with the titans. Fry’s account also provides a loose chronology of the birth of each of the gods, as well as the creation of humanity and its increasing interactions with the gods for good or ill.

Fry also attempts to give a wider cultural and intellectual context for the myths. First, there is the aetiological significance of the myths. Many of the myths tried to explain the natural world in some way, from Apollo’s (later Helios’s) driving of the sun chariot across the sky, to the story of Persephone, abducted by Hades and taken to the underworld where she ate six pomegranate seeds. Being the daughter a Demeter, a goddess of fertility and crops, her presence in the underworld led to wintry decline of the harvest. Her escape from the underworld, however, is conditional, since her eating of the six seeds requires her to return to Hades for six months each year. Hence, the cycle of the seasons.

Fry also provides interesting etymological discussions throughout the book. I’ve already mentioned Arachnae and spiders. There are many other examples. Ouranos, for instance, known as Uranus by the Romans, is imprisoned in the earth to become a simmering and angry god, waiting to be released. Our word uranium

is therefore derived from his name, just as plutonium

is derived from the Roman name for Hades: Pluto. Likewise, the Greek word for shield – aegis – underlies our meaning of the word when we use it to mean authority. Things are done under the aegis of…

, literally meaning that authority resides under some kind of protection. Fry also explains how the place names Oxford

and Bosporus

mean the same thing, denoting the crossing of the Aegean Sea from Europe into Asia by Io as a cow, harried by a gadfly sent by Hera. In Greek Bosporus

means cow-crossing, or a place where a cow might ‘ford’ a body of water.

But Fry wears his erudition lightly and his personality never fails to emerge. As a gay man (he thanks his husband Elliott in the Acknowledgements and counts Oscar Wilde as one of his heroes) he doesn’t miss the opportunity to make fun of himself. Fry recounts the many stories from Greek myth of beautiful young men who mostly came to some kind of unpleasant end as a result of their attractiveness: Ganymede, taken to Olympus to live with Zeus; Endymion forced into an eternal slumber so he might be raped repeatedly by Silene; Tithonus given eternal life but not eternal youth; Adonis killed by a boar while hunting; and Narcissus, who fell in love with his own reflection and was turned into the flower that bears his name. Each, Fry assures us, was a most incredible beauty, until he eventually feels forced to acknowledge the fading power of his own hyperbole: Oh dear,

he states, I’ve written this too many times for you to believe me again

.

There are too many tales and asides to give a full sense of the book here, but after all, that is the purpose of reading it. The book has two sections of coloured plates with examples of western art inspired by the myths Fry retells, which are credited in the back of the book. Fry also supplies an interesting Afterword which addresses the differences between myth and religion as he sees it, as well as his own very public atheism, and what the myths mean to him. Apart from that, the book also has an index which I found useful while writing this review. One criticism, however, is that there is no table of contents at the front of the book which would have been useful, given that Fry is attempting, as far as is possible, to create a chronology. However, I notice that a Contents page has been included in his follow-up book, Heroes.

Over all, the book is recommended because it is entertaining, informative and easy to read. As a guide, I know of a friend’s teenage daughter who read the book quite willingly.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed Facebook

Facebook Instagram

Instagram YouTube

YouTube Subscribe to our Newsletter

Subscribe to our Newsletter

No one has commented yet. Be the first!