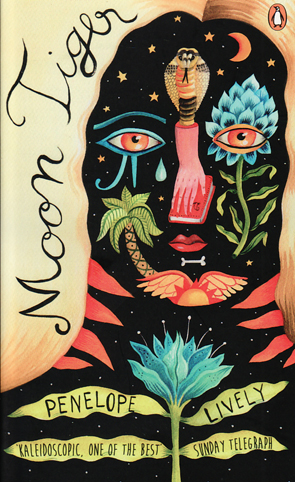

“I am writing a history of the world”. So begins Penelope Lively’s Moon Tiger. It seems an unlikely project, but Claudia Hampton, our protagonist, has written books about history during her life, and lived quite a bit of it, too. She was in Africa as a war correspondent when Rommel made his stand, rescued an eighteen-year-old boy from the Hungarian Revolution of 1956 and has had several lovers in her time. Claudia is highly intelligent, stubborn and not given to sentimentality. She distains her insipid sister-in-law, Sylvia, finds it hard to relate to her own daughter, Lisa, who has inherited none of her parents’ intellect, but is drawn to men with whom she shares qualities of strength. But now she is coming to the end of her life. Now she lays in hospital, drifting in and out of lucid states, visited by her family, dying of cancer.

The history Claudia claims to be planning is neither conventional, nor does it seem to be written. Her history is the narrative voice of this story, dipping into her life, revealing its secrets like a kaleidoscope – her word – constantly shifting and changing perspective, time and place, thereby eschewing the usual linearity of historical writing. It’s not such an unusual approach for a novel – there are many good books that abandon linearity – but it is less common in that it also incorporates multiple perspectives, both from other characters and, presumably, other Claudias. Claudia’s own perspective shifts between first and third person, and well-signposted shifts in perspective are made to other characters also, allowing the reader to revisit scenes to see their points of view. This has a weird effect sometimes, leaving the reader to wonder at the provenance of information; whether the narrative is controlled by an omniscient narrator not clearly defined or, indeed, whether Claudia just imagines and invents these other perspectives. A good example of this is when Lisa visits her mother in hospital. Lisa is not afforded much recognition in this story, so her revelation that she has a lover unknown to Claudia both characterises her as a more complete, independent person, but also challenges Claudia’s narrative control of the story:

You are not, as you think, omniscient. You do not know everything: you certainly do not know me. You judge and pronounce; you are never wrong. I do not argue with you; I simply watch you, knowing what I know. Knowing what you do not know.

It’s a moment in the narrative that seems to contrast with much of the book’s sentiment about history. The world history

of which Claudia speaks is, of course, not a world history in the conventional sense, but a personal account of twentieth-century history from Claudia’s perspective. As Claudia notes of the story of the Mayflower settlers, You are public property – the received past. But you are also private; my view of you is my own, your relevance to me is personal.

Official history is not what actually happened but the tidying up of this into books

, whereas Claudia’s view is that the voice of history, of course, is composite. Many voices; all the voices that have managed to get themselves heard.

She also observes, Moments shower away; the days of our lives vanish utterly, more insubstantial than if they had been invented. Fiction can seem more enduring than reality.

This is an observation that seems to direct the narrative. The problem of history – of imagining it, substantiating it and reproducing it – is central to this book. Whether it be in the historical books Claudia writes which she feels are analytical but her critics claim are sensational, Jasper’s historical documentaries which Claudia claims are spectacles rather than analysis, or the Plymouth Plantation, an historical theme park that seeks to recreate the life of American settlers in 1627 for visitors, but reveals their lives not in stark reality to Claudia, but as a mysterious impenetrable fog

, which facts and figures have no way of making real to her.

This was one of the most fascinating aspects of Moon Tiger. While Claudia travels in Egypt, seeing the pyramids and visiting Luxor, she is ultimately reminded of the anonymity of the individual to history. During the war she witnesses tanks and cars from a recent desert battle already being consumed by the desert, buried in sand. The columns of an Egyptian temple bear Victorian graffiti at their top. Claudia wonders how they got up there. But the columns have been rescued by the encroaching desert. A century ago, they, too, were almost buried. Likewise, the great ancient city of Memphis: And what is Memphis now? A series of barely discernible irregularities in the cultivation and an immense stone statue of Rameses the Second.

Even in Egypt, monumental and obsessed with preserving the self beyond death, history has erased all but the most powerful.

One of my favourite images in this book is of a photograph taken in 1868 of the village street of Thetford. There is a grocer’s shop and a blacksmith’s and a stationary cart and a great spreading tree, but not a single human figure.

William Smith, an engineer responsible for making important observations about fossils in geological strata, is said to have been in the town that day. Claudia imagines that he walked across the road and into the grocer’s shop while the image was being taken – probably a man on a horse and geese, too – but the exposure of the photograph – sixty minutes – was so long that William Smith and everyone else passed through it and away leaving no trace.

It is an insight that speaks much of one’s own place in history and the unique perspective one has of it: all of it ending in death; all of it forgotten once those who remember you die and are forgotten too.

The book is full of powerful imagery like this which heightens the understanding of Claudia’s experience and thought. I was interested in the imagery of the Moon Tiger. Claudia explains that a Moon Tiger is a green coil that slowly burns all night, repelling mosquitos, dropping away into lengths of grey ash, its glowing red eye a companion of the hot insect rasping darkness.

I remember using these coils when I went to New Guinea and the Philippines but had never heard them given this name. The coils seem like a solid coil on an electric stove top. They burn from the outer rim into the centre, and by the time they are done there is a ghost of ash in the shape of the coil lying on the floor. The coil is gone. Like history, we all bring our own understanding to metaphorical language. It seemed like an apt metaphor for life to me.

As morbid as all this may seem, the novel is really the contemplation of a life lived without apology. Claudia’s life is full and complex. Refusing to be defined by traditional sexual mores, she is both combative and supportive, loving and difficult. But for all the sense of independence she has enjoyed in life and the alienation she feels while dying in hospital, the novel also celebrates the importance of living with others. Because this is the ultimate mystery of history, after all; the empathetic connection not just with the received history of the world, but the history we write

ourselves. The novel mostly ends with a journal entry from the perspective of a lover important to Claudia’s sense of self. It is a demonstration not only of the problem of understanding history, since Claudia has already recounted this episode earlier in the novel, but the complex interconnections with others, with the wider world and history that defines the self.

I read this book after it was nominated for the Golden Man Booker Prize shortlist. I thought it was a worthy contender. The actual story, of which I have said little, is entertaining as are the characters engaging, while the book is philosophically satisfying.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed Facebook

Facebook Instagram

Instagram YouTube

YouTube Subscribe to our Newsletter

Subscribe to our Newsletter

No one has commented yet. Be the first!