In high school there was a student in our class with flaming red hair. Like many red heads, he received some teasing about it. One day another class mate asked whether his mother had red hair. He said no. He was asked if his father had red hair. He said no. Finally, he was asked the colour of the milkman’s hair. This was in the era when milk deliveries were still made by milkmen but the implication of this little joke remains obvious. The milkman is always a figure of adulterous jokes whose mere mention calls into question one’s paternity.

Anna Burns turns the milkman type into a far more threatening and mysterious character in her novel, Milkman. I didn’t know whose milkman he was,

says our unnamed narrator. He wasn’t our milkman. I don’t think he was anybody’s. He didn’t take milk orders. There was no milk about him. He didn’t even deliver milk.

The basis of the story lies in the narrator’s putative connection with the Milkman. The narrator has taken to walking while reading Ivanhoe (a book which recounts England’s occupation by Norman kings in the period after 1066) which unexpectedly draws the attention of the Milkman and the ire of many in the community. The Milkman opens the door to his van one day, claiming familiarity with her family, and encourages her to get in. However, the narrator is wary of the Milkman and refuses him. Nevertheless, he turns up from time to time, encouraging her confidence and revealing his intimate knowledge of herself and her family. The narrator, however, has been in a maybe relationship

with Maybe-boyfriend for the best part of a year. She understands the Milkman’s attraction to her, but he is over twice her age, she has become more serious with Maybe-boyfriend and she suspects Milkman is a spy or paramilitary. If she becomes involved with him her status will change in the community. There is a coterie of young women - groupies

- who desire exactly this kind of relationship with a renouncer-of-the-state, the more senior the better, so as to promote their own social standing. But the narrator is reluctant to engage in this kind of social mobility and rejects the Milkman, who unnerves her. Nevertheless, rumour has a way of becoming truth, and it is soon ‘known’ throughout the community that she is the Milkman’s girl, despite her resistance.

The setting for this novel seems indeterminate. The country is not named and most of its characters are never given a proper name. Apart from a group of English students studying French, the characters of this community remain anonymous types (Maybe-boyfriend

, in an almost relationship

with the narrator, tablet girl

, a woman disturbed by the insecurity of life in the district who undertakes to poison people around her, including tablet girl’s sister

, and the pathetic Somebody McSomebody

). It is a striking aspect of the book which foregrounds the issue of identity and loyalty. There is a list of banned names, for instance, that no one ever uses for their children in this community:

The names not allowed were not allowed for the reason they were too much of the country ‘over the water, with it no matter that some of those names hadn’t originated in that country but instead had been appropriated and put to use by the people of that land. The banned names were understood to have become infused with the energy, the power of history, the age-old conflict, enjoinments and resisted impositions as laid down long ago in this country by that country, with the original nationality of the name now not in the running at all.’

It doesn’t take long to piece together some obvious clues about the setting and the generic identity of these people and the country ‘over the water’. This is the 1970s, England is the enemy country and the resistance raised against the foreign force has brought about the the sorrows, the losses, the troubles, the sadnesses

. Milkman, therefore, is a thinly veiled representation of Northern Ireland during the 1970s and its Troubles.

Yet this is not a novel about the armed conflict. Instead, it tells the story from a female perspective. By decontextualizing the conflict – its place and its people’s identity – Burns is able to reify the often-overlooked issue of female experience in the conflict and the damage done not so much by bombs and guns, but by rumour and innuendo which subsume the interests of the individual to the service of tribalism.

This was an aspect of the book that I found telling. While the English are obviously the enemy, they are only ever periphery to the main conflict of the novel, which resides in the checks and balances of the Irish community, intent upon maintaining an identity distinct from their enemy, and thereby the will to continue the resistance:

‘Us’ and ‘them’ was second nature: convenient, familiar, insider, and these words were off-the-cuff, without the strain of having to remember and grapple with massaged phrases of diplomatically correct niceties … In those early days, those darker of the dark days, there wasn’t time for vocabulary watchdogs, for political correctness . . .

Burns, however, emphasises the internal conflict of the Irish resisters, creating a new dichotomy which replaces ‘Us’ and ‘them’

with a tension between the private and public self. The two milkman characters represent something of the dichotomy. One is a threat and portends a difficult future for the narrator. The other is benign and caring and offers hope. But in this political climate of checks and balances (Maybe-boyfriend is put under suspicion for having a car part that is rumoured to have an English flag on it) the personal is often community property and behaviour aberrant to community expectation places one beyond the pale

. The difficulty in making choices for happiness lies not only in the choosing, but because you have to fit convention, because you can’t let people down.

Even finding that perfect match and having a perfectly happy marriage is a potential affront to the community: Great and sustained happiness was far too much to ask of it.

This tension between the private and public, between familial and political duty, is represented to some degree by real milkman (as distinct from Milkman), who has eschewed the affections of many women since the death of Peggy (a named character, but who never appears in the story) whose long hiatus may be about to end. His following of middle-aged women is similar to the following the renouncers receive from their ‘groupies’, but instead of armed action in the name of politics, real milkman helps people he cares about. His presence in the narrator’s life and his mother’s previous and current interest in him also raises a question about the narrator’s paternity. I guess you could say that Burns is milking that old joke for all she can. But jokes aside, real milkman also offers the possibility of love and a normal relationship with his vehement rejection of the renouncers’ ideology and their attempts to bully him into cooperation.

Like many good writers, Burns deals with a few effective metaphors. One charming image is of the dance craze taken up by little girls in the district, imitating the pair of internationally renowned ballroom dancers from the district who have escaped its political turmoil forever (and happen to be the parents of Maybe-boyfriend). The girls are forced to dance with each other or dance on their own with a pretend-partner, since the little boys of the district are more interested in aping the paramilitaries, as they wanted to continue throwing miniature antipersonnel devices at the foreign soldiers from the country ‘over the water’ any time a formation of them appeared on our streets.

It is a nice symbol of the perpetuation not just of violence, but the continuing divide between masculine and feminine, as well as the public and personal personas of resistance.

There is also the metaphor of the sunset, introduced through the narrator’s French teacher. When she asks her pupils what colour the sky is, they reply that it is blue and find it difficult to accept any other answer. They’ve never really taken notice of it. When she insists that they watch a sunset the experience is a revelation to the narrator:

If what she was saying was true, that the sky – out there – whatever – could be any colour, that meant anything could be any colour, that anything could be anything, that anything could happen, at any time, in anyplace, in the whole of the world, and to anybody . . .

Her response is really a question about the ideology of tribalism – its rules concerning appropriate names, its pernickety insistence on certain behaviours, the certain narratives maintained by rumour and innuendo – which threatens the narrator with the weight of expectation and rumour from various sources throughout the book. Maintaining a sense of one’s self is shown to be difficult in these circumstances. The true enemy is not a country or soldiers on the streets, but ideologies, belief systems and the certainty of absolutist thinking. A sky may often be blue, but it can be many colours, after all.

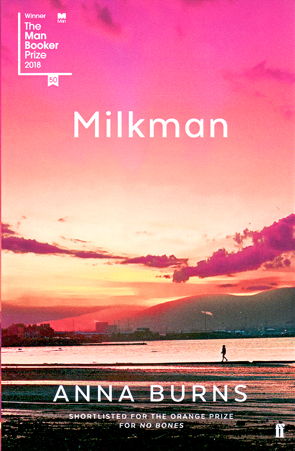

Milkman won the 2018 Man Booker Prize for literature. Its representation of a community at war with itself through rumour, extra-judicial punishments and fear is skilfully achieved. It also has a healthy dollop of the bizarre (there is a scene in which the narrator carries about a cat’s head in a handkerchief – read to find out why) and humour, achieved to a great degree by the extended milkman joke. While Ireland’s 1970s Troubles may be over, Burns has universalised her story through her fictionalised and indeterminate setting. It’s an interesting read.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed Facebook

Facebook Instagram

Instagram YouTube

YouTube Subscribe to our Newsletter

Subscribe to our Newsletter

No one has commented yet. Be the first!