Middlesex is a big book, an expansive book, weighing in at over five hundred pages. It’s the product of a prolific storyteller writing at what must be the top of his game. Middlesex delves into Greek history, brings us to the shores of modern America in the 1920s – a nation flexing its industrial muscle – and it invites us into the world of Calliope and her family, Greek immigrants to America, whose story spans three generations and most of the twentieth century. I say ‘her’, but the first thing we learn about Calliope is that her sexual identity is conditional: “I was born twice: first, as a baby girl, on a remarkably smogless Detroit day in January of 1960; and then again as a teenage boy, in an emergency room near Petoskey, Michigan, in August of 1974.” Calliope, later to be called Cal, is a hermaphrodite, or ‘intersex’, a term that is only tentatively being used in 1974 when Calliope is growing up.

Jeffrey Eugenides gifts his narrator with ‘prenatal omniscience’. Calliope is as digressive and playful as Lawrence Sterne’s Tristram Shandy, who purports to write about his own life, but fails to be born into his narrative until volume three. Like Tristram, it takes Calliope over a third of the novel to be born, because the story of her parents and grandparents is also her story, not just of her growing up and personal awakening, but of the recessive gene that has travelled through generations to make Cal who he/she is. Worthy of Sterne, Cal is cognisant of the moment of his own conception:

Inside my mother, a billion sperm swim upstream, males in the lead. They carry not only instructions about eye color, height, nose shape, enzyme production, microphage resistance, but a story, too. Against a black background they swim, a long white silken thread spinning itself out. The thread began on a day two hundred and fifty years ago, when the biology gods, for their own amusement, monkeyed with a gene on a baby’s fifth chromosome. That baby passed the mutation on to her son, who passed it on to his two daughters, who passed it on to three of their children (my great-great-greats, etc.), until finally it ended up in the bodies of my grandparents.

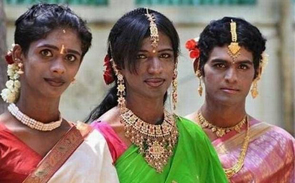

Cal is writing about his earlier life as Calliope growing up in 1970s Detroit from the perspective of an older man in the early 2000s living in Berlin and working in Foreign Services. In Cal’s present time he is making efforts to come to terms with his body and sense of self, so that he might live a more fulfilling personal life. This is the kind of book that would likely be banned in schools in Trump’s America, as an artefact of the culture wars that have been helping to reshape the nation: a book about sexual identity. While, at the time of writing, most Americans seem to support some equality for transgender people, a majority (60%) still believe that sex and gender are the same thing, thereby linking gender to an assigned sexual categorisation from birth. It’s a position explicitly rejected in the novel: “Sex is biology. Gender is cultural.” It sounds like a simplistic binary separation, but Cal’s story shows us that true binary thinking lies with the position that conflates sex and gender. For instance, Cal is biologically a male who has 5-alpha reductase deficiency, which affects his production of testosterone. Cal is identified as a girl when he is born, and is raised believing he is a girl, yet when he, as Calliope, fails to menstruate or develop breasts during puberty, but instead begins to exhibit male traits, he is taken to Dr Luce, a renowned sexologist, to understand what is happening. Cal has been raised as a girl, thinks he is a girl, but has had sexual stirrings inspired by another girl, known simply as the ‘Obscure Object’. In later life, at the beginnings of a relationship with Julie Kikuchi, Cal has to explain that he was not gay, though he thought himself a girl. And Zora (technically a male who presents as a female because her body is immune to male hormones), explains to Cal “… in some cultures we’re considered freaks … But in others it’s just the opposite. The Navajo have a category of person they call a berdache. What a berdache is, basically, is someone who adopts a gender other than their biological one.” Zora embraces her sexual identity (the novel uses the pronoun ‘her’ for Zora), neither wishing to identify as male or female, but as a hermaphrodite.

Calliope’s slow realisation about her body culminates in her belief that she is a ‘monster’, and fears rejection from her friends and family. The novel was first published in 2002, but it feels like it could have been written over twenty years later, it seems so relevant to our current time.

Yet narratively, Middlesex also has a lot in common with 19th century novels, even Greek tragedy. Cal is implicitly talking to a known reader throughout. His narrative voice is intimate and confessional, like Jane Eyre telling us of her marriage – “reader, I married him” – and draws the reader into his confidence: “I feel you out there, reader. This is the only kind of intimacy I’m comfortable with. Just the two of us, here in the dark.” However, Cal’s narrative style is also modern, playing with the impossibility of his own narrative insights: “Of course, a narrator in my position (prefetal at the time) can’t be sure of any of this,” he tells us, speaking of the intimate lengths his parents went to, to assure themselves of a daughter. Instead of nineteenth century realism, which is how this book mostly reads, the narrative is predicated upon the idea of the gene, which undermines traditional concepts of character. The gene has a story, too, its ‘long white silken thread’ connecting Cal biologically, through generations, to a fate. The idea is reified in the motif of Desdemona’s silk worms and the silk they produce. Desdemona is Cal’s maternal grandmother. While still living in Smyrna, before the Turkish invasion in 1922, her family made money from the production of silk. Cal associates Desdemona’s silk worms with the story of the Chinese Princess Si Ling-chi, who is said to have discovered the secret of silk when she walked into the Forbidden City and out into the countryside, unspooling a silk thread from its cocoon for over half a mile. “I feel like that Chinese princess,” Cal tells us. “Like her I unravel my story, and the longer the thread, the less there is to tell. Retrace the filament and you go back to a tiny knot, a first tentative loop.” This is the explanation of the impossibility of Cal’s narrative, how we accept that he knows the minute details of his parents’ and grandparents most intimate lives, the impossibility of which is only partly offset by the small confessions made to Cal later in the novel. Cal’s story starts in Greece with the incestuous marriage of his grandparents because it is that “tiny knot”, the “first tentative loop” of his fate. It is what makes Cal’s story a modern Greek tragedy, even if his story may seem ultimately uplifting: that like Oedipus, “the essence of tragedy … is something determined before you are born, something you can’t escape or do anything about, no matter how hard you try.” Calliope, in Greek myth, was one of the nine muses, inspiring epic poetry and eloquence. And so, Calliope, in beginning her story, anticipates her own creative fecundity by invoking the muse which is her namesake: “Sing now O Muse, of the recessive mutation of my fifth chromosome.” Fated never to have children of her/his own, Calliope/Cal creates, instead, an epic portrait of his family and his fated birth.

But this unspooling thread signifies more than one fated birth, or even the notion of sex and identity, in general. What makes Cal’s story compelling – beyond its sheer inventiveness – is that it is coupled with the emergence of modern thought predicated upon the conditions of a modern society. The idea that a person is defined by the State is first challenged by the Enlightenment revolutions of the 18th and 19th centuries, and the concept of the individual was championed by Romantics of that period. For centuries people were of a nation and subject to a lord or king. But in the modern world national identity is more fluid and less meaningful while sexual and racial identities have become contested spaces. Upon observing an Asian bicyclist (“Asian, at least genetically”) Cal decides the bicyclist is probably American. The modern world has made meaningless the boundaries once policed by traditional concepts of place: “You used to be able to tell a person’s nationality by the face. Immigration ended that. Next you discerned nationality via the footwear. Globalization ended that.”

The problematic notion of sexual identity is coupled with the problematic nature of identity, in general. Milton, Cal’s father, rejects his Greek Orthodox religion, even his Greek heritage. He is a child of Greek parents, but born and raised in America, much as Cal is a biological boy born and raised as a girl. Milton defines himself as a capitalist before anything else. For him, birth and nation are no longer determiners of his identity. But when Desdemona, Milton’s mother, working for the Nation of Islam, a pro-Islamic sect founded by W.D. Fard in Detroit, 1930, accidentally hears Fard’s preachings against white people echoed through the labyrinthine pipes and spaces of the Temple building as she works, her mind is turned by Fard’s racial doctrines. Fard’s doctrine holds that white people were distilled from a planned breeding program, breeding lighter and lighter skinned black people, until the white race emerged, weaker in every way except their ability to trick black people. Desdemona, who is susceptible to guilt over her consanguineous marriage with Leftie, is persuaded, somewhat, by Fard’s message. Exposed to the prejudices of Fard’s people, aware of her white complexion, guilty over her incestuous marriage, and aware of her own racial prejudices (especially against men wearing a Fez) Desdemona is inclined to understand the world in black and white terms. In America, race has always meant something. But for Milton, the Detroit race riots of 1967 are irrational. Cal describes them as a “guerilla uprising”, suggesting their planned and purposeful intent with a rational agenda based on racial inequality. But Milton dismisses the importance of race as nothing more than an excuse. In the middle of the riots Milton challenges Morrison, a local black businessman, “What’s the matter with you people?” Morrison’s reply, “The problem with us, is you?” becomes a dismissive mantra repeated by Milton over the years in a “black accent”. Milton mockingly refuses to believe in the underlying causes of disquiet in his community, which extends “not only African Americans but to feminists and homosexuals”. Unlike his mother, Desdemona, Milton is dismissive of identity issues that are irrational from the perspective of capital.

What is apparent, is that capital has replaced nation and king, and Milton’s identity is wholly engaged by that. He has run a speakeasy through Prohibition, has run a diner, and now makes his money off a chain of hotdog stands. His house on Middlesex Road, paid for with cash, is a Modernist trophy house that signifies his escape from the poverty of Detroit and its grasping issues of race. Capital is the new arbiter of identity, and other factors like race or sex are problematised by the world of capital. In the days when Cal’s grandfather, Leftie, worked at Henry Ford’s car plant, capital sought to reform humanity and every aspect of its workers’ lives: “Historical fact: people stopped bring human in 1913. That was the year Henry Ford put his cars on rollers and made his workers adopt the speed of the assembly line.” Once again, here is a parallel made between genetic adaptation and the rise of capitalism. Ford’s workers may have rebelled at the inhuman conditions of their employment, but Cal explains that modern living is an “adaptation”, passed down like genetic inheritance, from the first strictures of the assembly line:

They quit in droves, unable to accustom their bodies to the new pace of the age. Since then, however, the adaptation has been passed down: we’ve all inherited it to some degree, so that we plug right into joysticks and remotes, to repetitive motions of hundreds of kinds.

Ford’s company not only requires its workers to work like machines, but to adapt to a new ethos; to shed their old lives and old ways. They must learn English, and the company seeks to control every other aspect of its workers’ lives. Two men from the ‘Ford Sociological Department’ come to Leftie’s home to inspect his living arrangements: to advise upon his finances, how his food should be cooked, how to clean his teeth, and even with whom he may associate. It is an Orwellian level of control worthy of the treatment Huxley made of Ford’s ethos in Brave New World. It is an ethos determined to crush any notion of individualism with the imprint of a company worker.

Although a capitalist, himself, Milton has adapted and become that worker. He not only rails against his son’s Marxist girlfriend, Meg, who accuses him of exploitation, he not only has the trophy house, but he has the gun and the car, both emblems of American life, predicated on the capitalist ideal. In 1967, when Milton finally has enough money, he buys his first Cadillac, and every year after that he trades up. Calliope can trace her childhood by the model of Cadillac they own in any particular year. For Milton, the cars he owns are an extension of his self, a representation of his success. Milton has essentially bought into the Ford ideal (yes, the Cadillac is a General Motors car, but nevertheless), in which capital and work have defined who he is. As for his gun, a weapon he takes to protect his shop during the Detroit riots, it remains a potential throughout the narrative, which Cal cannot resist addressing in a narrative aside: the potential of Chekhov’s gun which the narrative demands, must be fired. Though, of course, the conflation of guns and genitals in popular parlance is a neat joke that ties these disparate aspects of the story together well.

Middlesex is too large a book, too generous in its narrative invention, to be able to speak about much of it. Why is Cal’s older brother called Chapter Eleven, for instance? It is generally recognised as the code for bankruptcy in America, affording the possibility of refinancing and rising again from the ashes. That’s the term Cal uses to describe Detroit after the riots: “A phoenix rising from the ashes.” The idea of rebirth, of starting anew, of redefining and adapting are strong motifs within this book. I wondered at Chapter Eleven’s name and realised that there are so many interesting details like this to follow in the novel, but entirely too many for a review like this to properly address. Like the unnamed ‘Obscure Object’, the girl whom Calliope develops a crush for, who is named after Luis Buñuel’s film That Obscure Object of Desire. Make of that what you will.

So, as I neared the end of the book, I began to wonder more generally about other books that had impressed me the way Middlesex has; for its sheer inventiveness, for the clever melding of different ideas and stories into a coherent whole. I thought of John Irving’s The World According to Garp, another book that touches on the subject of sexual identity. I thought about Steve Toltz’s A Fraction of the Whole, which is a great Australian yarn. And I thought about Michael Chabon’s The Adventures of Kavelier and Clay, which had similar elements of historical depth and rich invention. There would be other modern books, but these three came to mind first. If you’ve read any of them and enjoyed them, it is likely you will enjoy Middlesex.

Given the state of social debate at this time, Middlesex is a book that some would reject on the basis of its position on sexual identity. But this book is not a simple shot fired in the culture wars of identity politics. It is also a story about the modern world, about the changing face of America, as well as the impact of capital’s culture and how that impacts our sense of self. It is primarily a book about growing up. But most of all, it is a highly entertaining read, and well worth your time, even if you are uncomfortable with or do not support modern notions of identity around sex. On that subject, Middlesex is an informative book without its trying to proselytise. Apart from being entertained, you might learn something. I know I did. Highly recommended.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed Facebook

Facebook Instagram

Instagram YouTube

YouTube Subscribe to our Newsletter

Subscribe to our Newsletter

No one has commented yet. Be the first!