Men Without Women is a collection of seven short stories by Haruki Murakami. As suggested by the title, each of the stories has a male protagonist whose relationship with women is the subject. The stories reflect the stylistic range of Murakami’s longer fiction, from realistic narratives, to increasingly surreal or unsettling stories of loss or alienation. Yet connecting all these stories from first to last, is the idea that our identity – our sense of self – is not possible to know, except by examining our relationships with others.

In the first story, ‘Drive my Car’, Kafaku, a middle-aged actor, has been banned from driving after he was caught over the limit, and then found to have glaucoma. He is forced to engage the services of Misaki Watari, a plain woman whose driving skills overcome his prejudices about female drivers. Misaki remains professionally detached while Kafaku practises his lines in the car over the months that she drives him, until she wonders about his lonely existence. Kafaku, it turns out, lost his wife to ovarian cancer, but before that, he already sensed his loss over the course of her four affairs with fellow actors. Kafaku’s final attempt to posthumously seek revenge on her last lover, Takatsuki, was really an attempt to understand his own failing; what he lacked that his wife needed. Having befriended Takatsuki for this purpose, Kafaku is told by Takatsuki that, the proposition that we can look into another person’s heart with perfect clarity strikes me as a fool’s game

. Instead, Takatsuki advises Kafaku, Examining your own heart, however, is another matter. I think it’s possible to see what’s in there if you work hard enough at it … If we hope to truly see another person, we have to start by looking within ourselves.

‘Drive my Car’ sets the tone of much of the collection, with Murakami’s protagonist typically delving into their past, or finding revelation years after the events that have shaped them. In ‘Yesterday’ (another piece that reveals Murakami’s fascination with The Beatles) Kitaru seems incapable of progressing his life or defining his identity, so entrapped is he by his relationship with his childhood sweetheart, Erika. He has taught himself a fringe Japanese dialect in order to reinvent himself, but has marginalised himself from main Japanese culture as a result; he has failed his entrance exam to university twice and can’t bring himself to study for a third attempt, and now finds himself incapable of physically consummating his relationship with Erika in adulthood. Instead, he attempts to vicariously seek this experience by sending Tanimura, his friend and the story’s narrator, on a date with her.

There is a certain ambivalent detachment to women in several of the stories. Dr Tokai in ‘An Individual Organ’ is a plastic surgeon whose personal assistant not only organises his clients’ appointments, but also helps him to juggle several women at a time, always attached or married. Tokai does not want children, a wife or to complicate his life in any way with commitment. That is, until he meets a woman he cannot bear to lose.

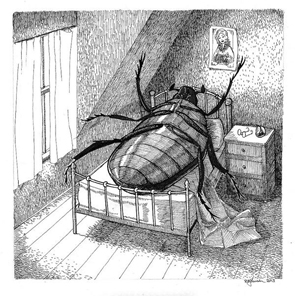

Murakami’s writing is economical throughout, and it is typical in stories like ‘An Individual Organ’ that he employs an apt metaphor. While Kafaku’s glaucoma bars him from driving, it is also the underlying weakness in his marriage; the ability to see someone else. Tokai is a plastic surgeon, and that suggests the level at which he has hitherto understood his women. But the title ‘An Individual Organ’, while it suggests the selfish nature of its protagonist – a heart singular and untouched by others – it is exemplary of Murkami’s skill as he defies expectation, to make the title an expression of the subject’s self-pity and misogyny. In ‘Samsa in Love’, Mukakami resurrects Kafka’s Samsa Gregor – this time he wakes confused to find he has turned back into a human – who is willing to accept his uncomfortable relationship with his new body when he finds himself attracted to a female locksmith (a hunchback no less) who has been called by his family to fix the lock of his imprisoning bedroom. In the surreal ‘Kino’, Murakami’s titular character is driven to seek an expression of his own humanity and to finally express a sense of loss over his wife, when he is mysteriously forced from his bar by the shadowy Kamita.

Not all the stories focus primarily upon men, however. ‘Scheherazade’, an obvious reference to the character from One Thousand and One Nights, is a nurse who looks after the needs of housebound Habara, including his sexual needs. But it is Scheherazade’s stories that awake in Habara a sense of his own humanity, because through her stories she reveals her own imperfect and fragile sense of self. Habara’s observation, prompted by the fear of losing her, might express the position of most of the men in this collection:

Perhaps an even more distressing prospect for Habara than the cessation of sexual activity, however, was the moments of shared intimacy. To lose all contact with women was, in the end, to lose that connection. What his time spent with women offered was the opportunity to be embraced by reality, on the one hand, while negating it entirely on the other.

This reality, a connection to one’s whole self, is lamented, also, by the narrator of the final piece, who is informed during a phone call in the middle of the night that a former girlfriend of many years’ past has killed herself. Reflecting on the loss to her husband, as well as the connection she offered the protagonist to a younger, more innocent self, he fears becoming a type – Men Without Women – applying the appellation as a plural to his singular self, suggesting not only the dehumanising effect of loss, but the humanising potential of relationships.

Fans of Murakami should love this book, and for those new to Murakami, this is a good introduction to his style, his key interests like music and recurring motifs like the moon, and the bizarre and even unsettling tone that characterises some of his writing. Some of the writing in this collection is masterful, and the collection as a whole offers a chance to reflect upon our relationships and the ways in which we are shaped by them. Highly recommended.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed Facebook

Facebook Instagram

Instagram YouTube

YouTube Subscribe to our Newsletter

Subscribe to our Newsletter

No one has commented yet. Be the first!